Find out about The Open University's Social Sciences courses

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Background

The town of Dumfries in South West Scotland has an industrial heritage that belies its image today as primarily a market town, regional centre and hub for the rural communities of Dumfries and Galloway. In particular, the town has a rich past as a location for the manufacturing of tweed cloth and hosiery. Alongside this lies another important legacy – a place of industrial disputes and trade union activity.

Before 1900 trade unionism in Dumfries was mainly in the form of male craft unionism. However, the expansion of the hosiery industry created employment opportunities for women workers and along with that the growth of trade unionism. This development reflected trends that were evident elsewhere across the country at the time, one significant element of which was the creation, in 1906, of the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), providing a union for women when many unions refused women members.

By the early 1900s Dumfries hosiery products – gloves, underwear, stockings and ties – were sold worldwide and the local industry was a major employer, with a workforce of approximately 1,500. This was boosted in 1908 when the Leicester hosiery firm of Tyler & Company opened a purpose-built factory for around 400 workers in the Maxwelltown part of the town.

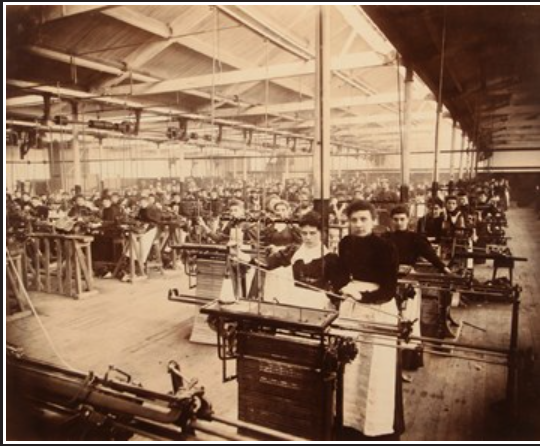

McGeorge's hosiery factory at Nithsdale Mills (c1910). Reproduced courtesy of Dumfries Museum.

McGeorge's hosiery factory at Nithsdale Mills (c1910). Reproduced courtesy of Dumfries Museum.

The four-week Ryedale strike – over ‘time-and-motion’ working and a pay cut – shows how the women organised, supported by the NFWW (1906-1921), Dumfries Trades Council (the local trade union grouping) and the local Independent Labour Party (ILP) branch. After a month – following arbitration – the women won their case and achieved a significant victory against an established national employer.

TUC History Online: The National Federation of Women Workers

Working Class Movement Library 2014: The Woman Worker, September 1907, Volume 1 Number 1

The Ryedale Strike, 1912

On Friday March 22nd, 1912, 150 women employed as ‘fingerers’ at Ryedale came out on strike. Though they were not union members, on Tuesday 26th, a Scottish NFWW organiser, George Dallas, arrived in Dumfries and addressed their meetings, helping to select a deputation of workers to meet the employers. The cause of the strike was an attempt by Tylers to introduce a new way of ‘fingering’ the gloves made at the factory, which the workers described in a letter to The Dumfries and Galloway Standard on the March 30th, 1912, thus:

The difficulty has arisen through a new method of joining the fingers–a method which all the girls agree takes longer to do. For this method of joining we were offered 11d per dozen – a reduction of 2d from the old way. After we came out our employers discovered how much work there really was in this new method, and they offered us 1s per dozen, which we refused.

Tylers wanted to cut the fingerers' piece rate from 1s 1d per dozen pairs of gloves to 11d. The women were told that, once used to a new working method, they would achieve their previous income by finishing gloves more quickly. At the old rate, on a 56-hour week, a worker producing 16 dozen pairs of gloves would earn 17s 4d; at the new rate, she would earn 15s 7d. An extra 24 pairs of gloves would be necessary to match existing weekly earnings.

The key element for the firm was the new way of working – they claimed this made a better joining. The workers argued that they could:

- continue with the old joining at 1s 1d

- do the new joining at 1s 1d or

- an easier joining at 11d.

Alongside the fingerers, employees working as ‘handers’ also raised an issue. Following an earlier change, their rate was cut from sixpence to fivepence-halfpenny per dozen pairs of gloves (after some less-skilled work was given to workers on a fixed wage). Both handers and fingerers were paid by the piece.

Communications and Concerts

The local newspapers were essential for information about the dispute, and both strikers and the firm tried to ensure their views were fully represented there. Identical letters often appeared in both papers, making claims and counter claims, but the strikers also held demonstrations in the town, attracting large crowds, and visited workplaces, collecting donations.

To increase support, the strikers organised concerts and, through the trades council, approached other unions for donations. At one concert, Dallas, in thanking the public for its support, said the ‘girls were fighting for every woman and girl in Dumfries’. Writing to the press he stated he had ‘never come across a more intelligent set of young women anywhere’. (as reported in the Dumfries Standard & Advertiser on 10th April 1912, page 6: ‘Ryedale Factory Strike: Concert in Aid of Strike Funds. The letter was in the same paper on 8th April 1912, page 4: ‘Glovemakers’ Strike’).

Moving to Arbitration

On 13th April both newspapers reported the appointment of the Board of Trade arbiter, Edinburgh University professor, Richard Lodge, who then visited Dumfries on Monday 15 April to hold his inquiry where he met Tyler and the strikers, the latter accompanied by NFWW officials. Following the meetings, the strikers began to resume work, and Tylers stated nobody would be penalised for involvement in the strike.

On 20th April, Professor Lodge’s decisions were announced. He supported the workers over the fingering dispute and instructed suspension of the fining for six months, followed by a review. He confirmed the new arrangement for the handers but insisted no-one be penalised for participating in the strike.

The Aftermath and the Strike’s Significance

However, five weeks later, the Standard reported ‘alleged victimisation of strikers’, with 23 employees dismissed or given notice, including several active in the new NFWW branch. The firm denied victimisation, arguing employees had complained about short time working. It had reduced the number of employees to give those still in work longer hours. The NFWW intervened to ensure there would be no more dismissals and 16 notices were withdrawn. A full review was agreed, though this was not reported in the press.

Despite the victimisation – of perhaps seven workers (or, following the review, perhaps none (the conclusions were not reported at the time) – the Ryedale strike was a remarkable achievement for factory workers in Dumfries, a town where there had been few, if any, trade union victories involving so many workers. It was effective action by, initially at least, non-unionised women, with major local impact through the Dumfries press and from the activities on the street and in the concert hall. It also demonstrated that, with support from local trade unions and the expertise of the NFWW, a group of organised women in a provincial Scottish town could win a dispute.

The banner image above shows Buccleuch Bridge in the foreground and, beyond, the medieval Devorgilla Bridge. (The Ryedale factory was at the top of the bank on the right of the river.)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews