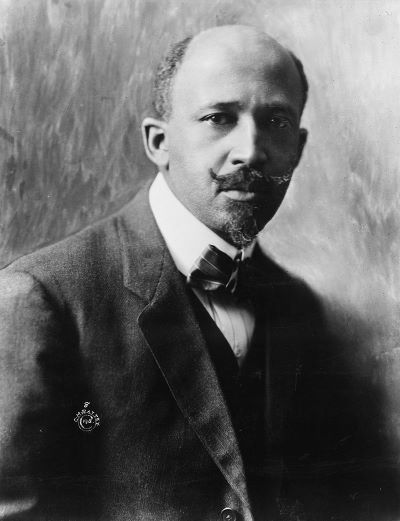

William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois was an extraordinary man, living in extraordinary times. He grew up in the North of America, where he went to a mixed school and his early talents were recognised and supported. His community collected money to send him to university; he was the first African American to be awarded a doctorate from Harvard. Throughout his career he was a strong advocate of the crucial importance of education, to lift and encourage people out of disadvantage and poverty. It would be fitting if we could draw on his work across the curricula to show how scientific and cultural discussion can identify the source, and help us find the solutions for social problems – some of which he would be gravely concerned to see continuing from the twentieth into the twenty-first century.

William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois was an extraordinary man, living in extraordinary times. He grew up in the North of America, where he went to a mixed school and his early talents were recognised and supported. His community collected money to send him to university; he was the first African American to be awarded a doctorate from Harvard. Throughout his career he was a strong advocate of the crucial importance of education, to lift and encourage people out of disadvantage and poverty. It would be fitting if we could draw on his work across the curricula to show how scientific and cultural discussion can identify the source, and help us find the solutions for social problems – some of which he would be gravely concerned to see continuing from the twentieth into the twenty-first century.

W.E.B. Du Bois was born in 1868, only nine years after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859, when John Brown tried to capture the arsenal and free slaves in the town, and three years after the end of the American Civil War (1861-65). He grew up during a time when efforts were being made to give black Americans equal rights, with the Ku Klux Klan and “Jim Crow” laws working against those efforts. He was a founding member of the Niagara Movement and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) – both key black civil rights organisations of the time (NAACP continues this work today). Du Bois produced a body of work. He wrote many books, including his famous autobiography Dusk Of Dawn, and was the founding editor of The Crisis, still the official journal of the NAACP.

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.I want to celebrate his work in Black History Month in order to persuade educators and researchers alike to look at his work across their curriculums and methodology discussions. Du Bois’s work offers great examples of how to represent reality (this is called mimesis); he used several different ways of doing this. He worked with statistics, and produced a major scientific study. He also found creative ways of representing statistical information in graphics which are admired to this day. To give people a realistic sense of African American lives, he used both a plain factual way of writing and a descriptive style of writing full of rich imagery.

Du Bois famously commented in his collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” His writing makes clear that it takes two sides to create a “color-line”. Only once both sides recognise and act to cross the line can it be erased. Utilising Du Bois’s work widely rather than just during Black History Month or in courses that look at African American experience, is one way in which the line can be crossed.

‘The Philadelphia Negro’ and ‘The Souls of Black Folk’

I’m looking here at two of the prolific canon of work that Du Bois produced, his study of African American urban life, The Philadelphia Negro, and his Homeric account (i.e. epic and poetic), The Souls of Black Folk.

The high levels of unemployment, imprisonment and drug addiction are linked and traced to the discrimination African American people face at every turn.Published in 1899, The Philadelphia Negro is one of our earliest and most rigorous social science studies. Du Bois moved with his wife and lived in the Seventh District of Philadelphia to undertake the study, making it an ethnography. This is where the researcher is immersed in the lives of the people they are writing about and can employ other social science methods of inquiry to collect data. Based on over 5,000 survey questionnaires and a mapping of every business and building in the Ward, this account of a diverse community provides the statistical evidence to show how African Americans were systematically disadvantaged. The high levels of unemployment, imprisonment and drug addiction are linked and traced to the discrimination African American people face at every turn.

Du Bois wrote this study two decades before the Chicago School – a group of social scientists in Chicago famous for their ethnographic accounts. Perhaps it’s not until the French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu and his team studied the banlieus (suburbs) of Paris in La Misère du Monde in the 1990s, that a sociological account of similar stature has been undertaken. For example, Wikipedia acknowledge that Du Bois’s is one of the earliest social science studies in its biographical account of him, but in their account of Social Sciences there is no mention of it. The Philadelphia Negro is a prime example of rigorous mixed methods research, unfortunately not acknowledged as such when the development of social sciences is looked at.

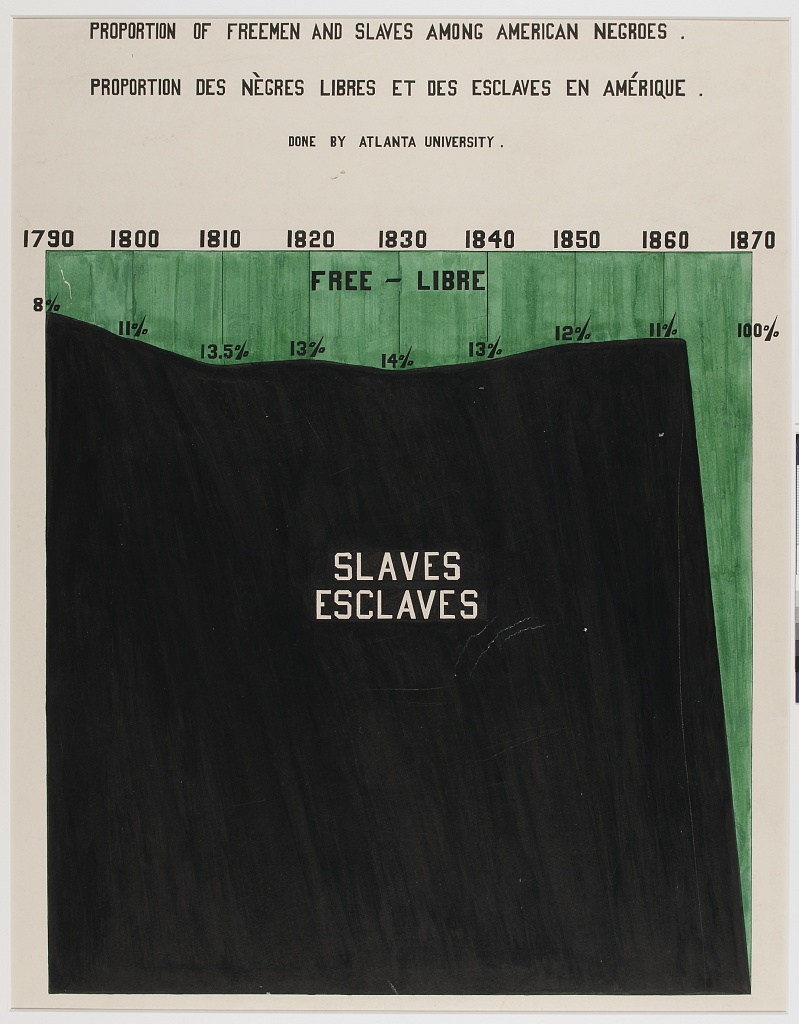

Graph entitled 'Proportion of Freemen and Slaves Among American Negroes', by Atlanta University students and Du Bois.

Graph entitled 'Proportion of Freemen and Slaves Among American Negroes', by Atlanta University students and Du Bois.

Du Bois at the Paris World Fair of 1900

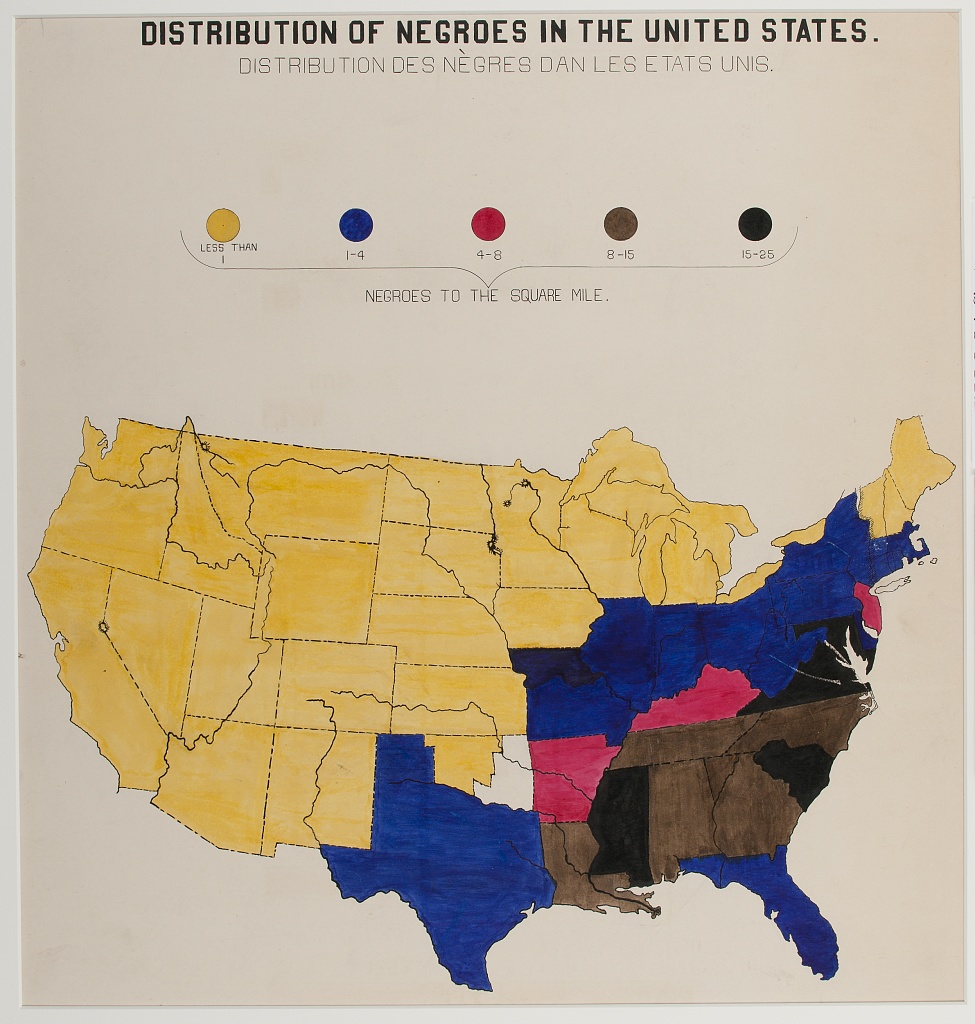

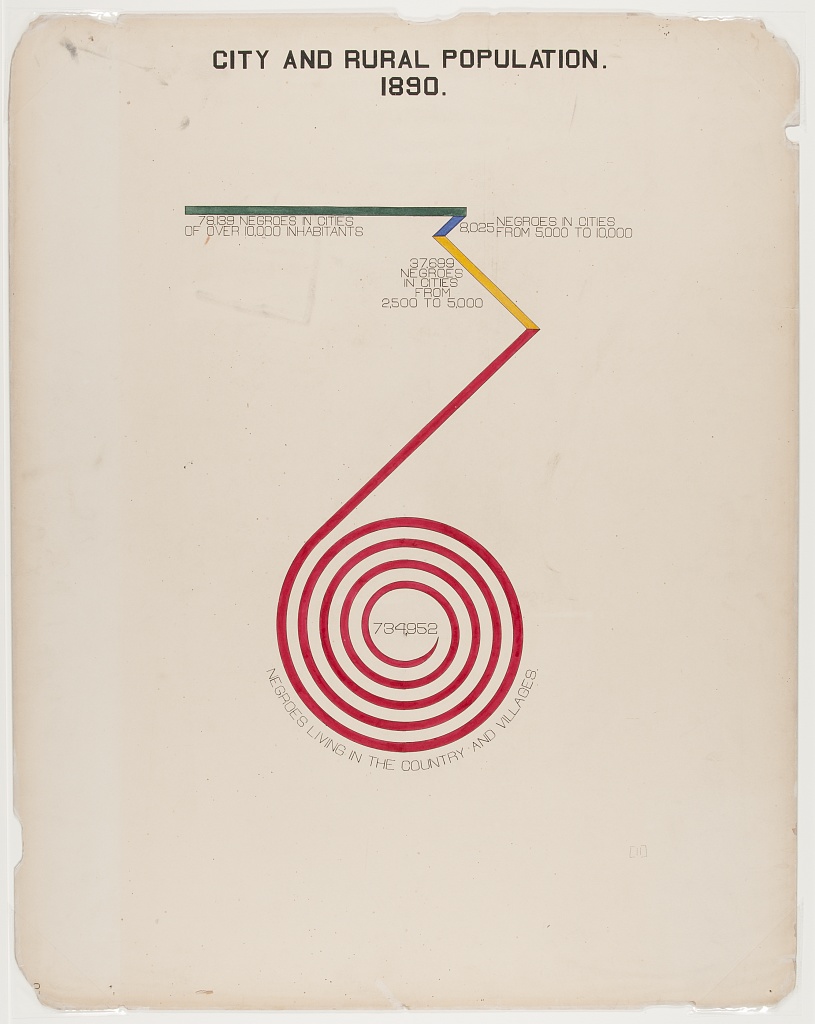

Du Bois was also sponsored by the US government to create an exhibit for the Paris World Fair of 1900. Working with a team, Du Bois figured out imaginative ways to represent the data he had collected so that it could be readily understood. These hand-painted pictures are a gift to anyone teaching statistics, offering lively discussion points about how to depict numerical data, so as to make an effective argument. Treasured today for their modernist artistic merit too, they show how art can convey social facts.

...they said that his knuckles were on exhibition at a grocery store.Du Bois was so determined to go to Paris to set up the exhibit that he collected money himself to pay for a passage, although he could only afford to travel in steerage, which is the lower steering deck, the cheapest section of the ship.

Compared to the racism of the United States in those days, Paris offered a liberal egalitarian welcome to African Americans – as musicians and artists of the 1920s discovered. (However, Frantz Fanon was later to write one of the most famous books on racism and colonialism about French culture: Black Skin, White Masks.) This would have been particularly welcome after an event that marks a turning point in Du Bois’s writing that of the terrible lynching of Sam Hose, an African American farm labourer wrongfully accused of murdering a white American. Up until this event, Du Bois must have had confidence and pride in the scientific way he had shown how African American people laboured to progress against insurmountable disadvantages. In his autobiography, he says:

I wrote out a careful and reasoned statement concerning the evident facts and started down to the Atlanta Constitution office, carrying in my pocket a letter of introduction to Joel Chandler Harris [journalist and (white) author of hugely popular stories drawn from African American culture]. I did not get there. On the way news met me: Sam Hose had been lynched, and they said that his knuckles were on exhibition at a grocery store farther down on Mitchell Street, along which I was walking. I turned back to the University. I began to turn aside from my work.

In Du Bois’s account we are more aware of the unspeakable pain he feels as a harsh factual reality because he gives no detail, just plain statement: they said that his knuckles were on exhibition at a grocery store. This writing is in a style discussed by the literary critic Auerbach in a famous study of the representation of reality in Western literature. Auerbach compares Homer’s Odyssey and the Bible, arguing that the flat undescriptive way in which the Bible presents stories makes them seem more real. In the same way, the flat undescriptive writing DuBois uses here makes his account seem more real.

Du Bois’s loss of faith in the scientific method as a means to convince society of the injustice experienced by African American people did not lead him to give up writing. It led him in a completely different direction, which again prefigures a famous sociological movement.

Before the great migration of the 20th century, black Americans mostly resided in the south - as depicted in Du Bois' original map.

Before the great migration of the 20th century, black Americans mostly resided in the south - as depicted in Du Bois' original map.

Du Bois: forerunner of Cultural Studies

Studying a community through a discussion of its culture – songs, habits of life and vignettes of individual lives is prefigured in The Souls of Black Folks.In 1957, Richard Hoggart wrote an account of working-class life through exploring magazines, comics, films. Up until this time, this had been regarded as ‘pulp’ – not worth critical interest. However, Hoggart’s discussion showed the wealth of social knowledge embedded in popular culture. Cultural Studies continued to develop in Britain to include research accounts of black and minority ethnic communities, under Stuart Hall at Birmingham University’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (Stuart Hall was later to become Professor at the OU.) Cultural Studies courses and projects are still very popular around the world, particularly in the USA and East Asia.

Studying a community through a discussion of its culture – songs, habits of life and vignettes of individual lives is prefigured in The Souls of Black Folks.

Du Bois sets out at the start the key concepts in his thinking:

- double consciousness: African Americans can see society both through their own experience, and understand how white people see it differently; and

- the Veil: it’s as if a veil hangs between African Americans and a full life, through which they can dimly see others aspiring and achieving as they try to do.

Here is the example in this quote:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

This richly poetic description is more Homeric than Biblical, however it too is a convincing representation of reality. A wealth of imagery conveys to us the aching reality of life in those times – and now: the sharpness of the line drawn between black and white communities, the striving of former slave communities to a better life and the many barriers which push them back into poverty. (Another great example of this writing in The Souls of Black Folk is the poignant chapter ‘Of the passing of the first-born’, with its pride and tender grief, and DuBois’s hesitant anxiety about how to parent a black child in a racist world.)

African Americans were largely concentrated in agricultural areas, as slavery had only been abolished less than 30 years earlier. This spiral chart by Du Bois shows the population of Georgia.

African Americans were largely concentrated in agricultural areas, as slavery had only been abolished less than 30 years earlier. This spiral chart by Du Bois shows the population of Georgia.

Final thoughts

Du Bois’s rich and varied ways of representing reality can be drawn on in many different kinds of teaching. Not only research methods teaching, his work could be used in literature and writing lessons to explore different ways of explaining the world, also in statistics and maths classes. As we wrestle with ‘fake news’, thinking about the ways we tell our stories and present factual information are increasingly important. Du Bois still has much to teach us here.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews