Find out about The Open University's Social Sciences courses

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Background

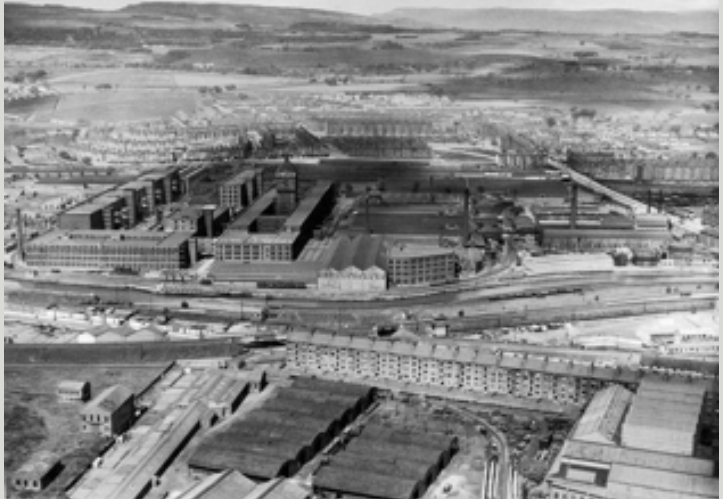

The Singer Manufacturing Company was one of the first multi-national companies. From their US base they expanded to Scotland in 1864, starting the assembly of sewing machines at a small factory just off John Street in Glasgow. Growing demand for their machines led them to transfer production to a new plant in Bridgeton before constructing a massive new factory on a greenfield site in Clydebank (population around 5,000) between 1882 and 1884. Within a year of production starting in 1884, they were employing around 5,000 workers, making it the largest sewing machine factory in the world. By 1911, the plant had expanded to employ over 12,000, around 3,000 of which were women. Census data from 1911 shows how the workforce was drawn, not only from Clydebank, but from all the adjacent communities along Clydeside, a factor that was to prove significant during the 1911 strike.

In tune with its American roots, the Singer Company was aggressively hostile to trade unions. They employed a plethora of anti-union tactics, including workforce spies and aggressive victimisation. The few union members in the plant would be confined to the male craft trades such as engineers, moulders and joiners. However, within the plant, the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) and the syndicalist International Workers of Great Britain (IWGB) were becoming active.

Singer and ‘scientific management’

Singer also imported new ‘scientific’ management techniques from the US in the form of ‘Taylorism’ which was becoming more widespread in Europe. These were closely intertwined with what became known as ‘Fordist’ style production processes. In the Fordist method, a version of which was introduced at the Singer factory, the labour process was fragmented into simpler and more repetitive tasks with the pace of work being dictated by the machines. Mass production under this system was pressured and dehumanising with the worker seen as just another cog in the process of maximising profit. Payment for work was on a piece rate system where every task was timed by foremen carrying stopwatches. The times would be set to the speed of the fastest, often the most experienced, workers. If work was rejected for quality problems, the worker would have to make up the shortfall to retain their earnings. The rate would then be cut as it had been proved they could work faster than had previously been the case.

These conditions were commented on by Clydeside socialist John MacLean in the Social Democratic Federation journal, Justice:

“The American Singers concern is Yankee from stem to stern…there are 41 departments and the various processes have been divided and sub-divided that I believe that few outside the office will know exactly how many processes the wood, the iron and steel have to go through before the machine is completed. Within recent years the sub-division of labour has been rapidly developed to an extreme, new automatic machinery has displaced labour, or at least enabled the management to enormously increase the output without a very great absorption of fresh workers” (Justice: 1 April 1911)

The strike begins

On the morning of Tuesday 21 March 1911, a work squad of fifteen women cabinet polishers was reduced to twelve resulting in an intensification of their workload with no commensurate increase in pay. The women resisted this blatant attempt by management at work intensification and stopped work, and were quickly joined by 380 out of the 400 workers in the department. On that day, the Glasgow Herald reported that initial support for the polishers came from around 2,000 female workers who left work “in feminine sympathy”. The following day, the strike spread rapidly, with 2,000 on strike by 8.00 a.m., growing to 10,000 by noon. By the Friday, the strike had been joined by a majority of the craftsmen, even though they had been instructed by their unions to stay at work.

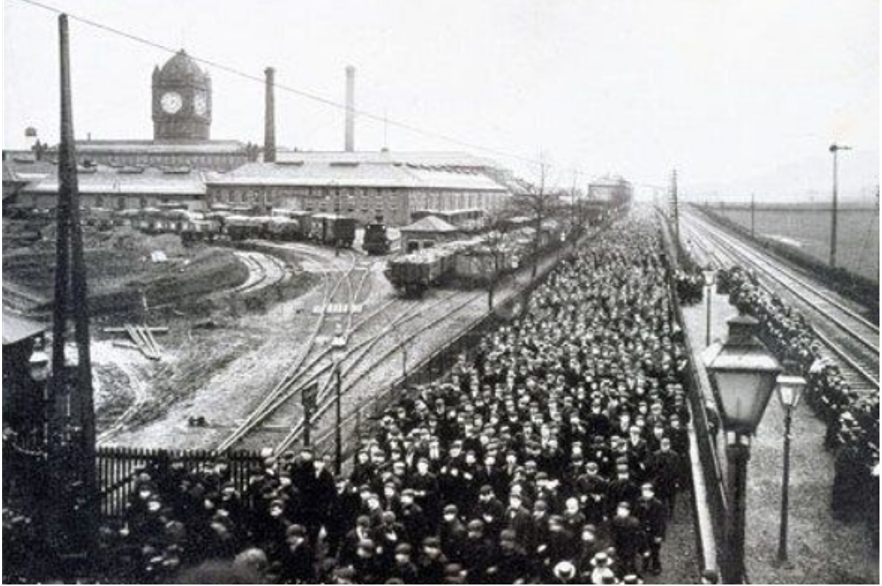

The massive Singer plant was at a standstill and the impressive scale of the action should not be underestimated. On the Thursday, 8,000 workers, headed by Clydebank’s Duntocher Brass Band, marched through the town and held a meeting outside the gates of John Brown shipyard asking for solidarity and support of the workers there. On the Saturday, the workers gathered at Kilbowie Park in the centre of Clydebank and headed to the factory to collect their wages.

“The procession, including as it did about 10,000 strikers was one of the most impressive spectacles which has been witnessed in the recent history of industrial strife. Although extremely quiet and orderly there was something extremely dramatic about the whole scene” (Glasgow Herald, 27 March 1911)

It should be noted that both the SLP and the IWGB were advocating non-violence and the Singer Company did not attempt to introduce replacement "blackleg" labour (that is, working despite an ongoing strike).

Organising the strike

Although the workforce was largely non-unionised, a strike committee was formed and the strikers’ demands focused on the issue of collective bargaining, anathema to a US multinational with an anti-union tradition. As the strike moved into the second week the initiative began to shift from the workers in favour of the company as they deployed all the mechanisms at their disposal, including increased intimidation of female workers. We have seen how the workforce was drawn from communities over a fairly large geographical area making use of the transport links from surrounding areas. Consequently the issues of communicating the demands of the strike committee to the workforce became increasingly difficult. This is where the company played its trump card. They, of course, had the names, addresses and check numbers of all their employees, allowing them to go over the heads of the strike committee and to letter the entire workforce individually. The letter outlined that the gates of the factory would remain open for a return to work only for a limited period. It also contained the threat that the work would then be transferred to other plants. Singer was a company operating across the world and had factories in Russia, Germany and the US, so this would not be seen as an idle threat. The letter also contained a postcard to be returned to the employer stating whether the worker was willing to return to work. The letters arrived as wages and lying time would have been exhausted, so most of the strikers would be running out of money as we have no evidence of any strike pay being available. This was no secret ballot, as the postcards would be easily identifiable, so we can see how the pressure was being exerted on the strikers.

On Friday 7 April, Clydebank’s Lord Provost, acting as independent adjudicator, certified the count as follows: Company 6,527 votes; Strike Committee 4,025 votes. Given the duration of the strike, the intimidation from the employer and alleged ballot rigging, the fact that 4,025 voted against a return to work shows the depth of the grievances. After the return to work, most of the activists and agitators paid dearly for their involvement through victimisation and blacklisting.

The strike’s significance

One of the most significant aspects of the strike was the role of women workers. Despite negligible levels of formal organisation, the female polishers did not hesitate to walk out over management’s blatant attempt at exploitation. Moreover, evidence suggests that female workers were among the first to come out in support of the female polishers, showing a high degree of gender as well as class solidarity. Two of the original strikers went on to serve on the strike committee of seven negotiating with the Singer management. They were resisting attempts by the employer to use them as a cheap, flexible secondary labour source. Some of this is even reflected in the comments of strike leaders at the time in the patronising language of the time referring to them as ‘the girls’.

The 1911 Singer Strike took place a few years before the wave of strikes which broke out across what became known as Red Clydeside during the First World War. It was a pointer to things to come.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews