Find out more about The Open University's History and Social Sciences courses

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Background

In the context of the growing ‘cost of living crisis’ in 2022, it’s unsurprising that trade union activity in Scotland has featured regularly in public discourse. Waste and recycling workers made headlines when they went on strike over pay and conditions in Glasgow during COP26 in November 2021; then in Edinburgh during the annual International Festival in August 2022.

Across Scotland, the railways and postal service have seen frequent disruption as workers are no longer willing to accept poverty wages while company bosses and shareholders profit from their labour. They are set to be joined by workers in a whole range of sectors, including health and education in late 2022 and into 2023.

In October 2022, the University and College Union (UCU) became the third trade union to secure a national mandate for action since the introduction of the Conservative trade union laws introduced in 2016 aimed at curtailing industrial action by unions, joining RMT and CWU. Over 70,000 university staff at 150 institutions are set to act, beginning in November 2022 and escalating in early 2023 at the beginning of the new semester. The higher education sector faces significant disruption, with sister unions UNISON and UNITE, representing some of the lowest paid workers in universities, having also secured mandates for action in some institutions (in a disaggregated ballot).

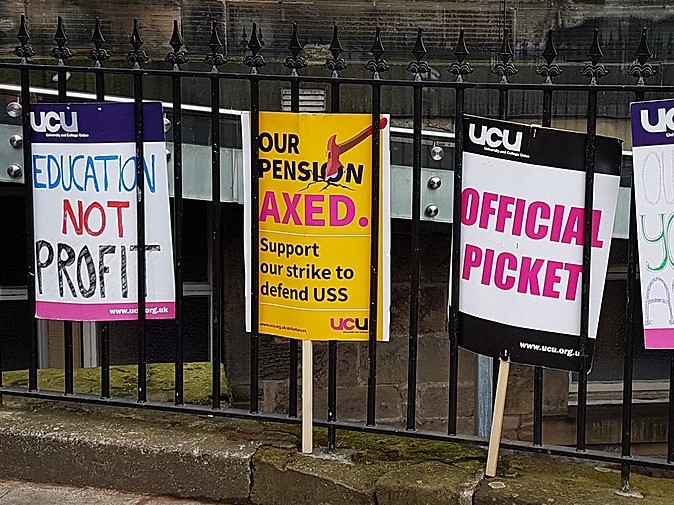

UCU picket line, Glasgow University, March 2021.

UCU picket line, Glasgow University, March 2021.

The UCU and the 'four fights'

For UCU members, the call to renewed action in 2022 is the latest in a long and ongoing dispute. UCU has, in fact, been engaged in strikes and other forms of action almost continuously since 2018, over attacks on workers’ pensions and what has come to be known as the ‘four fights’: falling pay, high levels of casualisation, workload and equalities issues. Like many other workers, university staff made significant sacrifices and adaptations to their work during the COVID-19 pandemic to support students. Yet the value of pay in higher education fell by 17.6% relative to inflation between 2009 and 2019. Meanwhile, in 2021, massive cuts were made to the USS pension scheme, leaving university workers concerned about their retirement.

Edinburgh University UCU ‘Four Fights’ Leaflet, 2022Levels of casualisation are

extremely high in the sector, with one-third of all academic staff in the UK employed

on fixed-term contracts (UCU website). This figure rises to almost half for

teaching-only academics (44%) and over two-thirds (68%) for research-only

staff. Workloads are also extremely high, with reports of academic staff

working on average two days unpaid per week. The pay gap between Black and white

staff stands at 17%, and the disability pay gap is 9%. The mean gender pay gap

is 16% and at the current rate of change it will not be closed for another 22

years. (More information on the dispute is available on the UCU website.

Edinburgh University UCU ‘Four Fights’ Leaflet, 2022Levels of casualisation are

extremely high in the sector, with one-third of all academic staff in the UK employed

on fixed-term contracts (UCU website). This figure rises to almost half for

teaching-only academics (44%) and over two-thirds (68%) for research-only

staff. Workloads are also extremely high, with reports of academic staff

working on average two days unpaid per week. The pay gap between Black and white

staff stands at 17%, and the disability pay gap is 9%. The mean gender pay gap

is 16% and at the current rate of change it will not be closed for another 22

years. (More information on the dispute is available on the UCU website.

With figures such as these, one could be forgiven for thinking that the HE sector in the UK was in a poor place financially. Yet in 2021, UK universities generated a record income of £41.1bn. UCU estimates that university vice chancellors collectively earned around £45million in the same year. The sector has money to spend; yet it prefers to invest in campus expansions and high salaries for those at the top and in grandiose ‘flagship schemes’. Meanwhile, university workers’ calls for fair pay and better conditions have been ignored by Universities, and by the Colleges Employer’s Association (UCEA) and Universities UK. The figures above illustrate how widespread problems within higher education are, but speaking to activists on the ground offers more of an insight into both the realities of working in academia and being involved in the fight to improve conditions.

One UCU rep explained that she left a permanent lectureship at a different institution during the COVID-19 pandemic because of an unsustainable workload and poor management. She is now working on a fixed-term research contract and commented that while being insecurely employed is challenging, permanence can also be used to pressure staff into accepting high workloads as they ‘need to be grateful’. In many cases, there is a gendered aspect to this. Providing pastoral care for students was described as highly gendered, putting particular pressures on junior female staff in particular.

A culture of pressure and

exploitation within academia was also emphasised: ‘Academia can take, and

take, and take. If you’re someone who wants to support students and colleagues,

this can easily become exploitative’. This was echoed by another UCU rep,

who stressed that the conditions staff are working in undermines the student

experience: ‘we care about the quality of their education, we’re advocates

for that’. Indeed, one rep stated that as a student she had learned about disputes

from her lecturers, and when entering academia herself: ‘I knew it was a

workplace you’d need to fight, to defend yourself’. All the reps interviewed

believed the whole academic system to be exploitative, and while there are

targeted fights on issues such as pay and pensions, it was also claimed that

this is a fight more generally to reclaim higher education as a force for good.

Union activism in a precarious working environment

Being an activist within UCU is an important identity, particularly for precarious workers, with one rep explaining that it offered a stable identity – something that they lacked in a professional sense because of them having to move between institutions: ‘it’s hard to have an identity when temporary’. Another rep said that becoming a committee member helped them become more visible in their academic department, and they are now seen as a ‘safe person’ to talk to about a range of issues.

The importance of the ‘local’ context was emphasised by UCU reps. While we negotiate with national bodies, particularly on pay and pensions, a lot can be won at the local level. Indeed, it is where action on other areas of the ‘four fights’ dispute is most needed. One activist suggested that people get a ‘taste’ of collective action at the local level and can be empowered by this, so our job is to ‘find where people are challenging inequalities on the ground and bring our networks and expertise to support them’.

At a local level, there have been examples of progress at some institutions, including at the University of Glasgow. The four campus trade unions (UCU, Unison, Unite and GMB) have worked together to secure a local pay uplift from management which will help mitigate the impact of the cost-of-living crisis. This has involved close relationships with the other trade unions, which is a priority for the current leadership. There is an active anti-casualisation sub-committee within UCU Glasgow which has produced reports on the realities of casualisation at the university and is involved in discussions and negotiations to tackle casualisation. There are also newly established workload and equalities sub-committees, working to produce similar research.

Growing the Union

The OU Branch is the largest in the UCUUCU reps also talked about the

value of the union as a vehicle for a range of social justice issues, including

feminism and anti-racist organising, and fighting to get a ‘seat at the

table’, a say in decision making – for example in university discussions on

sustainability. But it was strongly felt that there is more to be done to grow

our union, both at a local and national level. Some activists emphasise that we

need a more active membership which has an organising rather than a ‘service’

model, with union membership often being quite passive. It was felt that more local

agency is needed regarding union decision-making and strategizing. Working

closely with our sister unions is also considered critical. At a local and

national level our union is growing at a critical time, and this means we must

learn and adapt to ensure we are organising as effectively as possible.

The OU Branch is the largest in the UCUUCU reps also talked about the

value of the union as a vehicle for a range of social justice issues, including

feminism and anti-racist organising, and fighting to get a ‘seat at the

table’, a say in decision making – for example in university discussions on

sustainability. But it was strongly felt that there is more to be done to grow

our union, both at a local and national level. Some activists emphasise that we

need a more active membership which has an organising rather than a ‘service’

model, with union membership often being quite passive. It was felt that more local

agency is needed regarding union decision-making and strategizing. Working

closely with our sister unions is also considered critical. At a local and

national level our union is growing at a critical time, and this means we must

learn and adapt to ensure we are organising as effectively as possible.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews