Find out more about The Open University's History and Social Sciences courses.

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Background

On Tuesday 25 October 1955, members of the General Iron Fitters Association at Rolls-Royce in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, took unofficial strike action. By Thursday 27 October, workers in various unions at other Rolls-Royce plants in the west of Scotland, at East Kilbride and Hillington, had joined them (BBC Newsreel, 1955). Altogether, around 11,000 workers took unofficial strike action (Daily Worker, 1955; Blantyre Gazette, 1955). This dispute, in which many women workers were involved, lasted until 14 December 1955 (The Daily Telegraph, 1955).

Comparatively little is known about this dispute, and the fact that Rolls-Royce once operated at three plants in the west of Scotland has also largely been forgotten.

There is only one aero-engine plant now operating in the area, located close to Glasgow Airport at Inchinnan, Renfrewshire.

Rolls-Royce first came to the west of Scotland in the early years of the Second World War, with a ‘Shadow Factory’ established at Hillington on the Southwestern outskirts of Glasgow. Work at this plant, to produce ‘Merlin’ aeroengines for RAF Spitfires and other warplanes, shadowed an established Rolls-Royce factory at Derby which, being further south and east, was more easily reached by the Luftwaffe.

In the post-war period, at the East Kilbride plant, it was the ‘Avon’ jet engine which was the focus of production.

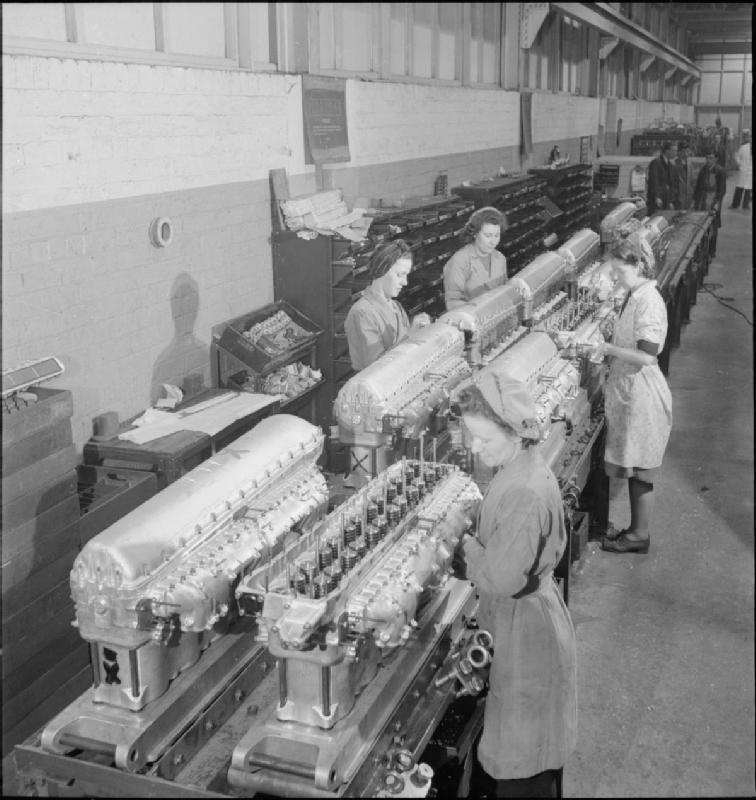

Rolls-Royce Merlin engine production line, 1942. Merlin engines were used in Spitfire and Hurricane fighters.

Rolls-Royce Merlin engine production line, 1942. Merlin engines were used in Spitfire and Hurricane fighters.

The dispute

Striking Women Workers at Rolls-Royce Blantyre, 1955

(Image with kind permission of Paul Veverka, The Blantyre Project)Across

the three plants, there were concerns that redundancies were on the horizon. In

response, workers at the Blantyre plant agreed to restrict overtime and to

share the work equally. One worker at the Blantyre plant, after initially

agreeing to the rationing of work, did the opposite and instead ‘hogged’ work

resulting in his pay being well above that of his colleagues. Though his name

was Joe McLernon, he quickly became known as ‘Bonus Joe’ (New York Times,

1955).

Striking Women Workers at Rolls-Royce Blantyre, 1955

(Image with kind permission of Paul Veverka, The Blantyre Project)Across

the three plants, there were concerns that redundancies were on the horizon. In

response, workers at the Blantyre plant agreed to restrict overtime and to

share the work equally. One worker at the Blantyre plant, after initially

agreeing to the rationing of work, did the opposite and instead ‘hogged’ work

resulting in his pay being well above that of his colleagues. Though his name

was Joe McLernon, he quickly became known as ‘Bonus Joe’ (New York Times,

1955).

The ‘Bonus Joe dispute’ erupted at a time when closed shop arrangement was gaining traction in UK workplaces. Not surprisingly, it was hugely controversial, giving rise to a long-running debate in the UK Parliament and within the trade union movement itself about the closed shop practice (Hansard, 1955). The dispute at Blantyre was widely reported in the newspapers from Belfast to New York, though there was little attention given to the role of the women workers in the fight for 100% trade unionism (Belfast Telegraph, 1955; New York Times, 1955). The only newspaper to mention the role of women was the Daily Worker.

The controversy around the closed shop and the strike at Blantyre also provoked reaction from the organised churches in Britain. The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Hamilton Presbytery of the Church of Scotland and the Catholic Bishops issued statements to the press urging the workers to return to work (Blantyre Gazette, 1955; Daily Worker, 1955; Dundee Courier, 1955). Notices were read out in chapels in areas where the factories were located and where Roll-Royce workers lived, warning them about ‘the evil machinations of Communist shop stewards’ (Belfast Telegraph, 1955). This will not have resonated well with workers who knew that there was, in fact, only one Communist Party member (William Wilson) on the shop stewards committee at Blantyre.

As well as the clergy, the employers and Conservative government used the press and its political allies to warn about strikes. Lord Bilsland warned that ‘strikes drive away industries’ (Dundee Courier, 1955). Lord Hives told Roll-Royce shareholders: ‘your company will oppose with all the means within its command any attempt to use the cloak of trade union activity to achieve political objectives … and which in this case were so blatantly used to prejudice the liberty of an individual’ (Daily Herald, 1956).

Campaigning for equal pay

Though mainstream press reports at the time highlighted the Bonus Joe story, this was taking place in the context of a wider campaign for equal pay across many sectors of the economy. Women strikers across the three Rolls-Royce plants in West Central Scotland simultaneously fought for the principle of 100% trade unionism (the closed shop) and for equal pay. A UK-wide petition for equal pay for women engineers organised by the AEU (Amalgamated Engineering Union) had been in circulation and was delivered to the Westminster Parliament. This was followed by a demand by five engineering unions to employers on 21 December 1955, for equal pay for women workers (Daily Telegraph, 1955). According to press reports the women organised a 2,000-strong demonstration and marched to Glasgow Green in support of their demands (Daily Worker, 1955).

Rolls-Royce, Hillington. The facility was constructed during the Second World War as a manufacturing plant for the Merlin engine.Rolls-Royce Hillington had been the site years earlier in 1943 of a

campaign for equal pay for women engineers, led by the indomitable Agnes

McLean. McLean led a fight within

the AEU for the right of women to be unionised. Having achieved this in the

face of fierce opposition from some quarters within the AEU, McLean then organised

thousands of women workers at Rolls-Royce in a campaign for equal pay (Bain, 1995).

It is unlikely that the women workers at Rolls-Royce in 1955, would not have

been in some way familiar with the story of Agnes McLean who had by that time

attained almost celebrity status locally as a result of her trade union

activities (The Herald, 2017).

Rolls-Royce, Hillington. The facility was constructed during the Second World War as a manufacturing plant for the Merlin engine.Rolls-Royce Hillington had been the site years earlier in 1943 of a

campaign for equal pay for women engineers, led by the indomitable Agnes

McLean. McLean led a fight within

the AEU for the right of women to be unionised. Having achieved this in the

face of fierce opposition from some quarters within the AEU, McLean then organised

thousands of women workers at Rolls-Royce in a campaign for equal pay (Bain, 1995).

It is unlikely that the women workers at Rolls-Royce in 1955, would not have

been in some way familiar with the story of Agnes McLean who had by that time

attained almost celebrity status locally as a result of her trade union

activities (The Herald, 2017). Workers across the 3 plants lobbied the 13 unions that represented them to make the strike official. Trade union leaders did not declare the strike official until 23 November (Daily Worker, 1955; Financial Times, 1955). Meanwhile, the strike action was gathering support with unofficial action being taken in industries outside the Rolls-Royce stable. Significantly, the Clyde Workers Committee, which had played a crucial role in the 1943 equal pay dispute, had vowed to support the strikers, to raise solidarity donations and, crucially, to spread the strike (Daily Worker, 1955; Bain, 1995).

The Clyde Workers Committee, the world’s first shop steward’s organisation, is synonymous with successful workplace and community-centred rent strikes during the period of ‘Red Clydeside’ around the First World War, producing from within its ranks highly influential trade union leaders and political activists like Willie Gallacher and John McLean among others. According to the Daily Worker, the Saracen foundry in Springburn in the North of Glasgow voted for solidarity strike action (Daily Worker, 1955), local miners donated £500 to a strike fund and there were attempts to spread the strike to Rolls Royce plants in England (Daily Worker, 1955). The Financial Times described the dispute as part of a ‘disturbing trend’ (Financial Times,1955).11,000 workers campaigned for equal pay in the face of opposition from the government and from trade union leaders. Women workers at Blantyre, East Kilbride and Hillington, were not passive bystanders in the shaping of labour relations in the post-war period. Women actively claimed their rights, stood their ground and demanded wage equality and political equality. Moreover, they demonstrated their commitment to trade union organisation and in particular to the struggle for the closed shop. (It is worth noting that the TUC did not wholly support the closed shop at this time.) Women’s role in this action has been largely hidden by the mainstream press reports which portrayed this astonishing example of unofficial solidarity action as being about ‘one man’ (The Daily Telegraph, 1955). Ultimately 100% Trade Unionism was effectively outlawed by the first woman Prime Minister in the UK, Margaret Thatcher, in the Trade Unions Act, 1980 (Dorey, 2009). Rolls-Royce closed the Blantyre plant in 1977. Although the principle of equal pay is now enshrined in law, the struggle over enforcement continues.

Legacy

The courage, determination and militancy of the women workers at Rolls-Royce in their trade union and equal pay struggles during the 1950s has been largely hidden. This is but one example, albeit a notable one, where women were to the fore in trade union action, and it is fair to assume that there were other places across the UK, likewise unrecorded or undiscovered thus far, where similar action took place. Their dispute is a reminder of how ‘official’ history can render women invisible. Their fight deserves to be read, to be heard and to be celebrated.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews