- Change and continuity as communities come and go

The Boundary Estate housing development, which has Arnold Circus at its heart, was designed to remedy the desperate poverty of slums that were cleared to provide the space for it. But the rents of this first council housing estate were too high for the displaced residents. The slum dwellers of the Old Nichol were pushed eastwards, making way for the ‘deserving poor’ who could afford the rents of Arnold Circus.

Today, it’s still a battle to keep Arnold Circus as social housing for the ‘deserving poor’. Residents, fearing a rise in rents and ultimately gentrification, have twice seen off attempts by Tower Hamlets Council, which currently owns 60% of the flats, to sell Arnold Circus to a local housing company.

Arnold Circus, London

From the dilapidation and squalor of the Old Nichol slums to the ‘fairly comfortable’ residents of England’s first ‘council estate’.

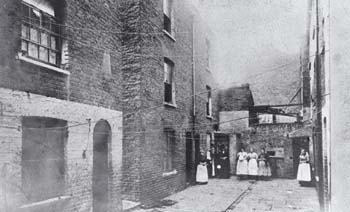

Arnold Circus, London in the 19th century

Arnold Circus, like other streets, has been made by the people who arrive and those who leave. Before Arnold Circus was built, the notorious Friars Mount slum in the Old Nichol occupied the area. Quoting the vicar of St Philips, the church of the Old Nichol, Friedrich Engels wrote, ‘It is nothing unusual to find a man, his wife, four or five children, and, sometimes, both grandparents, all in one single room of ten to twelve square feet, where they eat, sleep and work.’ English text of Engels' Condition of the Working Class in England , 1845.

To remedy what Engels described as ‘a mass of helplessness and misery’, London County Council cleared the slum and built Arnold Circus. Unfortunately, the original slum inhabitants could not afford the rents of these first council houses so they were forced into new slums further to the east.

The Boundary Estate: mapping poverty

In the 19th century, people were concerned about poverty and the condition of the working classes. They carried out door to door surveys and one of the most comprehensive of these was that done by Charles booth. With his team of researchers, he visited every street in London, producing detailed notebooks, surveys and poverty maps.

Booth's notebooks described the buildings and the inhabitants in great detail, often including moral comments about the workers and their living conditions.

Living conditions in the Old Nichol were grim

It was described in 1896 by campaigning author, Arthur Morrison, in his novel ‘A Child of the Jago’, as being ‘for one hundred years the blackest pit in London’.

TRANSCRIPT: In 1889 when he first turned off Shoreditch High Street and into the slum, Booth was stepping into an unknown world. He discovered that streets once famed for silk weaving had become a densely populated warren. A single house here contained 60 people, there was barely any sanitation and the streets were filled with human excrement, fostering deadly diseases. Life expectancy for the poorest of Victorian Shoreditch was just 16.

The clip is reproduced with permission from the BBC.

'Semi-vicious and criminal classes'

The streets of the Friars Mount slum in the Old Nichol, which would eventually be cleared to build Arnold Circus, were coloured black by Charles Booth in his earlier survey of 1889, to denote the ‘semi-vicious and criminal classes’ who lived there.

Although Arnold Circus was built to remedy the desperate poverty of the slum it replaced in the Old Nichol, none of the original slum dwellers could afford the rents of the new council houses. They were forced further to the east, creating new slums in areas such as Dalston and Bethnal Green.

Dramatic changes in living conditions

Arnold Circus was colour-coded by Charles Booth in his 1898 survey as pink: ‘Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings’. Its inhabitants were ‘usually paid for responsibility and are men of good character and much intelligence’.

Newly-built, Arnold Circus replaced the notorious slums of the Old Nichol. Booth noted five-storey flats with shops underneath and two schools. One is still a school today.

For more information about the Booth maps, visit the London School of Economics website.

Arnold Circus, London in the 20th century

Arnold Circus residents come and go, reflecting the waves of migration into London.

Arnold Circus residents come and go, reflecting the waves of migration into London.

The Boundary Street Estate

Arnold Circus tells a history of comings and goings. The Boundary Street Estate, with Arnold Circus at its centre, was a ‘model development’ providing all that the residents would need.

It was at the heart of London County Council’s Boundary Estate, one of the first attempts by a local authority to create social housing. Some of its first tenants were Jews escaping pogroms in Europe. In the 1930s, Jews fleeing Nazi persecution arrived until they were, in turn, replaced by migrants from Bangladesh in the 1960s and 1970s. This history of comings and goings is depicted in the lives of many local buildings like the Jamme Masjid mosque on nearby Brick Lane. Buildings have identities too. Since the early 1700s each wave of immigrants to nearby Arnold Circus has established its own place of worship in this building from Methodists to Jews to Muslims.

Britain's first council estate

TRANSCRIPT: In 1890, two years after Booth's visit to Shoreditch, the newly formed London County Council moved to compulsorily buy every hovel in the Shoreditch slum. It intended to demolish them all. In their place, the LCC would build its own homes. Unlike any private landlord the ambition was not to build for profit but to provide decent homes for the most miserable of London's poor. This would be Britain's first council estate. Called the Boundary Scheme work began in 1894 when almost fifteen acres of the worst streets of Shoreditch were flattened. The streets were rearranged to radiate out from one circular street named Arnold Circus after an LCC official. The man behind the layout was the chief architect of the Boundary, Owen Fleming, he was just 23.

The clip is reproduced with permission from the BBC.

The Boundary Estate: an exercise in social engineering?

Not only would the Boundary Street Estate be a ‘model development’ it was also an experiment in social engineering. While the existing schools and churches were included in the plan, there would be no pubs and no shops would be able to sell liquor.

This photograph from 1895 shows the foundations of the Estate taking shape with the demolished slums in the background.

Where did the displaced slum-dwellers live?

TRANSCRIPT: This LCC map marks with a black dot the final location of all the families made homeless when the slum was destroyed. It reveals how they circled around the Boundary, but ultimately stayed in the miserable streets outside it. Not a single former slum dweller moved into Arnold Circus. The first council estate was built to improve the lives of the most miserable in the Victorian city. The poorest didn't benefit at all.

The clip is reproduced with permission from the BBC.

Buildings have identities too

Now a mosque, this remarkable building provides a physical timeline. Since the early 1700s, each wave of immigrants to Arnold Circus has established their own place of worship here on Brick Lane. The building began life as a church for the French Huguenots, fleeing religious persecution in the 17th century. In the late-19th century, it was converted into the Machzike Adass or Spitalfields Great Synagogue.

With the arrival of immigrants from Bangladesh, it became the Jamme Masjid or Great London Mosque in 1976. It is currently undergoing a major restoration programme.

To find out more visit the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid website.

Distinctive design: a 'hidden' gem

Five-storey mansion blocks of varying sizes were built along wide, tree-lined streets, radiating from a central garden, with shops, schools and laundry for residents. The launderette and school remain today, serving the lively local community.

The distinctive design of Arnold Circus and its close proximity to the City of London means that its apartments remain in demand. They are both privately owned and rented from Tower Hamlets council.

Jews in Arnold Circus, 1900

TRANSCRIPT: The first tenants of the two bedroomed flat presently occupied by young professionals Richard Wallace and Kate Beckett were Celia and Simon Finklestein. They were not from the slum, they'd come to the East End from Russia, some time in the 1870s, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews fleeing religious persecution in eastern Europe. Simon Finklestein had found work in the local industry that was even older than the slum, the garment trade. By 1896 Simon Finklestein was doing well enough out of tailoring to afford to become one of Britain's first council tenants. On Arnold Circus, the Finklesteins climbed the social ladder without losing touch with their Jewishness. In 1900 one of Booth's researchers took social mapping in a new direction. He mapped the Jewish population in east London. Brick Lane, the centre of the garment industry was blue, over 95% Jewish. Half a mile to the north is Arnold Circus, here the blocks were individually mapped one is dotted blue, over 75% Jewish.

The clip is reproduced with permission from the BBC.

More stories behind the streets

-

Upper Buckingham Street, Dublin, Ireland: from speculative landowners to multi-tenanted tenements

Take part now to access more details of Upper Buckingham Street, Dublin, Ireland: from speculative landowners to multi-tenanted tenementsThe story of Upper Buckingham Street, from its initial layout in 1788 to the present day, reflects the ups and downs of Dublin city and its people.

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

-

Park Hill, Sheffield: continuity and change

Take part now to access more details of Park Hill, Sheffield: continuity and changeWhat stories does Park Hill hold? From 19th century industrial squalor to iconic 'streets in the sky' in the 1960s, Park Hill, Sheffield changes once again as we enter the 21st century.

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

-

Great Ancoats Street, Manchester: cottonopolis to urban village

Take part now to access more details of Great Ancoats Street, Manchester: cottonopolis to urban villageWhat are the stories behind this unique 'urban village'? From the largest mills of Manchester's 19th century industrial era to slum dwellings in the 1920s. 21st century Ancoats sees revamped canals, squares and modern, stylish apartments.

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

-

Dumbarton Road, Partick, Glasgow: from tenements to riverside apartments

Take part now to access more details of Dumbarton Road, Partick, Glasgow: from tenements to riverside apartmentsWe look back at the social history shaped by a ten-fold rise in population from 5,000 in 1850 to over 55,000 by 1901, and forward to the Glasgow Harbour regeneration scheme.

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

-

The stories behind our streets

Take part now to access more details of The stories behind our streetsWhere do you live? One answer may be your home postal address but what are the secrets behind your postcode? How has your street changed over the years?

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

Rate and Review

Rate this activity

Review this activity

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Activity reviews

Even tho there was good intention behind Arnold Circus, it didn't sort the inequalities and constraints from the poorest who couldn't choose to rent an accommodation there.Food for thought

I have seen differences in housing association accommodation versus council and private and its sad to see the inequalities.