How copyright works

Copyright applies to works of original authorship, which means works that are unique and not a copy of someone else’s work. Most of the time this requires fixation in a tangible medium, meaning that the work needs to be written down, recorded, saved to your computer, etc.

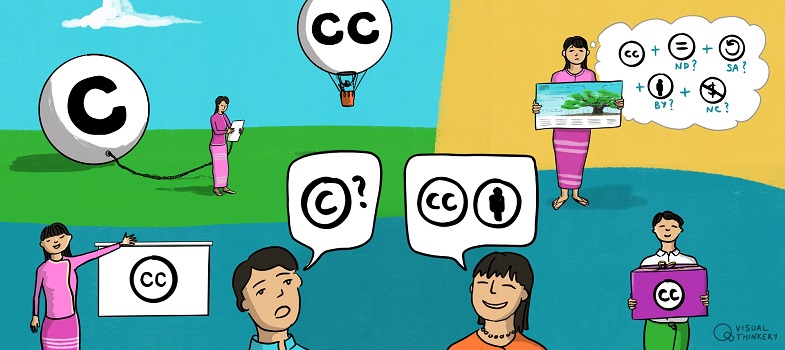

Copyright law establishes the basic terms of use that apply automatically to these original works. These terms give the creator or owner of the copyright certain exclusive rights, while also recognising that users have certain rights to use these works without the need for a licence or permission.

What’s copyrightable?

In countries that have signed up to the major copyright treaties described in more detail in Section 1.2, copyright exists in the following general categories of works, although sometimes special rules apply on a country-by-country basis. A specific country’s copyright laws almost always specify types of works within each category. Can you think of a type of work within each category?

- literary and artistic works

- translations, adaptations, arrangements of music and alterations of literary and artistic works

- collections of literary and artistic works.

Additionally, depending on the country, original works of authorship may also include, among others:

- applied art and industrial designs and models

- computer software.

As we will see, Myanmar’s 2019 Copyright Act covers all these categories of works.

What are the exclusive rights granted?

Creators who have copyright get exclusive rights to control certain uses of their works by others, such as allowing others to:

- create authorised translations of their works

- make copies of their works

- publicly perform and communicate their works to the public, including via broadcast

- create adaptations and arrangements of their works.

(Note that other rights may exist, according to the country’s laws.)

This means that if you own the copyright to a book, no one else can copy or adapt that book without your permission (with important caveats, which we will discuss in Section 1.4).

Keep in mind that there is an important difference between being the copyright holder of a novel and controlling how a particular authorised copy of the novel is used. While the copyright owner owns the exclusive rights to make copies of the novel, the person who owns a physical copy of the novel, for example, can generally do what they want with it, such as loan it to a friend or sell it to a used bookstore.

One of the exclusive rights of copyright is the right to adapt a work. An adaptation (or a derivative work, as it is sometimes called) is a new work based on a pre-existing work. The new Myanmar Copyright Act protects adapted work but does not include a definition of this term. However Sections 13 and 18(b) of the Act indicate that work that changes from one format to another (from written form to an audiovisual format, for example) will be protected. This means that a work that is created from a pre-existing work can only be created with permission of the copyright holder. It is important to note that not all changes to an existing work require permission. Generally, a modification rises to the level of an adaptation, or derivative, when the modified work is based on the prior work and manifests sufficient new creativity to be copyrightable, such as a translation of a novel from one language to another, or the creation of a screenplay based on a novel.

Copyright owners often grant permission to others to adapt their work: translated novels or screenplays adapted from novels are common examples of this. Adaptations are entitled to their own copyright, but that protection only applies to the new elements that are particular to the adaptation. For example, if the author of a poem gives someone permission to make an adaptation, the person may rearrange stanzas, add new stanzas and change some of the wording, among other things. Generally, the original author retains all copyright in the elements of the poem that remain in the adaptation, and the person adapting the poem has a copyright in their new contributions. Creating a derivative work does not eliminate the copyright held by the creator of the pre-existing work.

Although the term ‘derivative work’ includes but is not limited to the way in which ‘adaptations’ are described in the Berne Convention in some countries, for the purposes of this course and understanding Creative Commons we will use these terms interchangeably.

Does the public have any right to use copyrighted works that do not violate the exclusive rights of creators?

All countries that have signed up to major international treaties grant the public some rights to use copyrighted works, without permission, without violating the exclusive rights given creators. These are generally called ‘exceptions and limitations’ to copyright.

Many countries itemise specific exceptions and limitations, while others use flexible concepts such as ‘fair use’ and ‘fair dealing’. We’ll return to look at what exceptions are included in Myanmar’s new Copyright Act in Section 1.4.

What is important to know is that copyright law does not require the permission of the creator for every use of a copyrighted work. Some uses are permitted as a matter of copyright policy that balances the sometimes competing interests of the copyright owner and the public.

What else should I know about copyright?

As noted at the beginning of this unit, copyright is complex and varies around the world. This unit serves as a general introduction to its central concepts. There are a number of additional concepts that it might be useful to have an awareness of (such as liability and remedies, licensing, and transfer and termination of copyright transfers and licences) and you can find out more about these in the additional resources [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] section.

Further, there are additional considerations for some creative works that copyright law may not address. Cultural and historical contexts and contingencies can influence people’s decisions to use creative works. Traditional Knowledge labels offer identifiers for creative works, recognising their cultural heritage and significance to the communities from where the works originated.

The purpose of copyright