The 2019 Copyright Act

Myanmar’s new 2019 Copyright Act protects all original literary and artistic works from being transmitted, distributed, adapted or reproduced without prior permission from the copyright owner. The Act applies to all works regardless of their mode or format of expression, their content, quality and purpose. The new Act therefore covers both physical and digital formats. It also covers work created by hand (such as paintings or sculptures), or manufactured work. As we saw, earlier work is automatically covered by copyright when the creator starts to put something into a tangible form: for example, if it is written, painted or drawn. Consequently there is no requirement for registering copyright.

The 2019 Act also introduces new terms of copyright protection. In general, copyright protection is the lifetime of the creator plus 50 years after their death. However, audiovisual or cinematographic work will be protected for 50 years from the year it was first made publicly available. Applied arts will be protected for 25 years from the date at which an object was first made.

Work created by both citizens and residents in Myanmar will be covered by the new Copyright Act. However, in the case of broadcasting, audiovisual and cinematographic works, creators should be Myanmar residents or have their office or business in Myanmar. Architecture is only protected under the new law if the respective building is located in Myanmar. Regardless of citizenship or residency, creators are protected by the new Act if their work is performed or first published in Myanmar.

As we will see in Section 1.3, Myanmar citizens’ creations will be covered by copyright in other countries, if Myanmar is a signatory to a number of international treaties.

As noted earlier, the Act also covers ‘adaptations’ – that is, changing a work from one format to another – although there is no definition of this term within the Act. This requires further clarification in the forthcoming Copyright Rules, which were being drafted at the time of writing (September 2020).

There is also an opportunity for the new Copyright Act to clarify whether websites that respond to copyright owners’ requests to remove material posted by others have violated copyright, such as Facebook posts that contain copyrighted content. Outdated copyright law means that currently there is a ‘safe haven’ for websites with regard to copyright notices and takedowns, so websites are not liable for copyright infringement by users. You can find out more about what measures are being taken elsewhere in the world to address this in the additional resources [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] section.

The new Copyright Act will also introduce severe penalties for anyone who violates the law. The minimum penalty will be imprisonment for a term of no more than three years or a minimum fine of 1 million kyat (approximately US$1000), or both. For repeat offenders, sentences will range from three to ten years’ imprisonment plus a fine of no more than 10 million kyat (approximately US$10,000). However, there are some circumstances where copyrighted material can be used without requiring permission from the copyright holder. (These specific circumstances are discussed in Section 1.4).

Section 90 of the new Copyright Act includes provision for a two-year transition period in which the production of unauthorised copies of protected work is still permissible. However, after this period has passed, you will no longer be able to make copies, change or share material without the copyright holder’s permission. So it’s important to start thinking now about what changes you might need to make to your own practice and that of your university or college to ensure that you are ready to comply with the new Act. We will discuss in more detail the implications for Higher Education in section 1.4.

You can read Myanmar’s 2019 Copyright Act (available in Myanmar language), and a number of English-language summaries are provided in the additional resources section.

You may also want to explore the website of the Myanmar Intellectual Property Department, and the Facebook page of IP Myanmar, which regularly posts on intellectual property matters.

Frontier magazine also examines Myanmar’s copyright law and its possible implications, and you can also read EIFL’s assessment of the new law.

Exclusive rights in the new Copyright Act

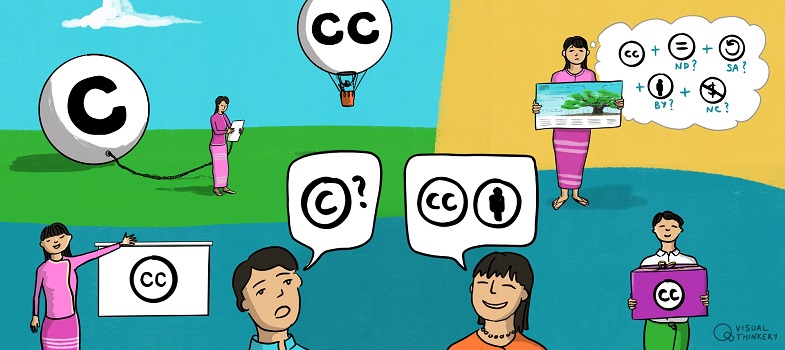

There are two other categories of rights, called exclusive rights, that are included in the new Myanmar Copyright Act. These exclusive rights are important to understand because, as we’ll see in Section 3.2, the rights are licensed and referenced by Creative Commons licences and public domain tools.

- Moral rights: As mentioned above, moral rights are an integral feature of many countries’ copyright laws. Under the new Myanmar Copyright Act, moral rights last for the lifetime of a creator plus an unlimited period after their death. However, moral rights can be waived under certain conditions. Although Myanmar has not currently signed the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (the ‘Berne Convention’), these rights are recognised in Article 6b. (We will look at the Berne Convention in more depth in Section 1.3.)

- Similar and related rights (including rights known in many countries as ‘neighboring rights’): Closely related to copyright are similar and related rights. These relate to copyrighted works and grant additional exclusive rights beyond the basic rights granted to authors described above. Some of these rights are governed by international treaties, but they also vary country by country. Generally, they are designed to give some ‘copyright-like’ rights to those who are not themselves the author, but are involved in communicating the work to the public: broadcasters and performers, for example. Section 2 of the new Myanmar Copyright Act includes similar and related rights specifically in relation to performers, audiovisual producers and broadcasting organisations. The Act covers not only communication to the public but also importing, uploading on the internet and selling to the public for the purpose of distribution.

As we will see in Unit 2, Creative Commons licences and public domain tools cover these rights, allowing the public to use works in ways that would otherwise violate those rights.

A history of copyright in Myanmar