Introduction to the global copyright system

International laws

Every country has its own copyright laws, but over the years there has been extensive global harmonisation of these laws through treaties and multilateral and bilateral trade agreements. These establish minimum standards for all participating countries, which then enact or conform their own laws to the agreed-upon limits. This system leaves room for local variation.

These treaties and agreements are negotiated in various fora: the World Intellectual Property Organisation (known as ‘WIPO’), the World Trade Organisation (known as the WTO) and in private negotiations between select countries.

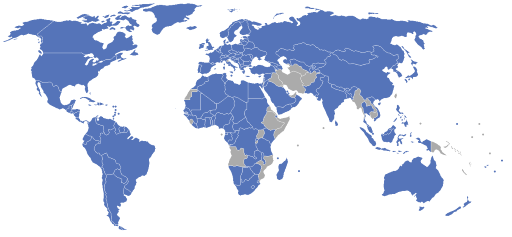

One of the most significant international agreements is the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , concluded in 1886. The Berne Convention has since been revised and amended on several occasions. WIPO serves as administrator of the treaty and its revisions and amendments, and is the depository for official instruments of accession and ratification. As of June 2020, more than 179 countries have signed the Berne Convention. In South East Asia only Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar have not yet signed it. This treaty (as amended and revised) lays out several fundamental principles upon which all participating countries have agreed. One of those principles is that copyright must be granted automatically – that is, there must be no legal formalities required to obtain copyright protection: for example, national laws of its signatories cannot require you to register or pay for your copyright as a condition to receiving copyright protection. In general, the Berne Convention as revised and amended also requires that all countries give foreign works the same protection that they give works created within their borders, assuming the other country is a signatory. The following map shows (in blue) the signatories to the Berne Convention as of 2012.

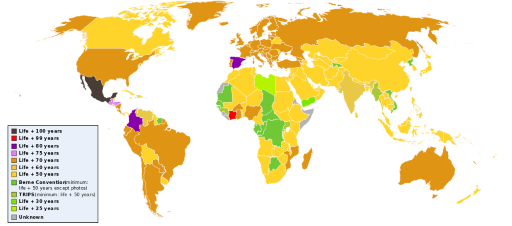

Additionally, the Berne Convention sets minimum standards – default rules – for the duration of copyright protection for creative works, although some exceptions exist depending on the subject matter. The Berne Convention’s standards for copyright protection dictates a minimum term of life of the author plus 50 years. Because the Berne Convention sets minimums only, several countries have established longer terms of copyright for individual creators, such as ‘life of the author plus 70 years’ and ‘life of the author plus 100 years’. The following map shows the status of copyright duration around the world as of 2012.

In addition to the Berne Convention, several other international agreements have further harmonised copyright rules around the world.

Although Myanmar is not currently a signatory to the Berne Convention it has signed up to nine treaties related to intellectual property rights. These include the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation, World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) which all World Trade Organisation (WTO) members abide by. TRIPS requires its members to enact intellectual property laws, including copyright. Myanmar has been granted several extensions to enable the laws to be enacted and the final deadline for implementation is 1 July 2021. For a full list of these intellectual property treaties, see additional resources.

As noted earlier, work by Myanmar citizens does not currently have the same copyright protection elsewhere in the world. For work created by Myanmar citizens to be afforded copyright protection in other countries, Myanmar needs to be a member of the Berne Convention (1886), WIPO Copyright Treaty (1996) and the Marrakesh Treaty (2016) when the new Copyright Act is implemented. The WIPO and Marrakesh treaties cover digital resources and facilitate the sharing of resources for people who are blind or have visual impairments, respectively.

National laws

Although international frameworks exist because of the Berne Convention and other treaties and agreements, copyright law is enacted and enforced through national laws. Those laws are supported by national copyright offices, which in turn support copyright holders, allow for registration and provide interpretative guidance. As mentioned, while there has been a major effort to create minimum standards for copyright across the globe, countries still have a significant amount of discretion as to how they meet the requirements imposed by treaties and agreements. That means the details of copyright law still vary between countries. You can find out more about Myanmar’s Intellectual Property Department and how it can support you on its website.

What law applies to my use of a work restricted by copyright?

A common question of copyright creators and users of their works is which copyright law applies to a particular use of a particular work. Generally, the rule of territoriality applies: national laws are limited in their reach to activities taking place within the country. This also means that generally speaking, the law of the country where a work is used applies to that particular use. If you are distributing a book in a particular country, then the law of the country where you are distributing the book generally applies.

This is true even in the era of the internet, although it is much more difficult to apply. For example, if you are a Canadian citizen travelling to Germany and using a copyrighted work in your PowerPoint presentation, then German copyright law normally applies to your use.

It can be complicated to determine which law applies in any given case. This complexity is one of the benefits of Creative Commons licences, which are designed to be enforceable everywhere. We’ll find out more about Creative Commons in the next unit.

Overview