Enter Creative Commons

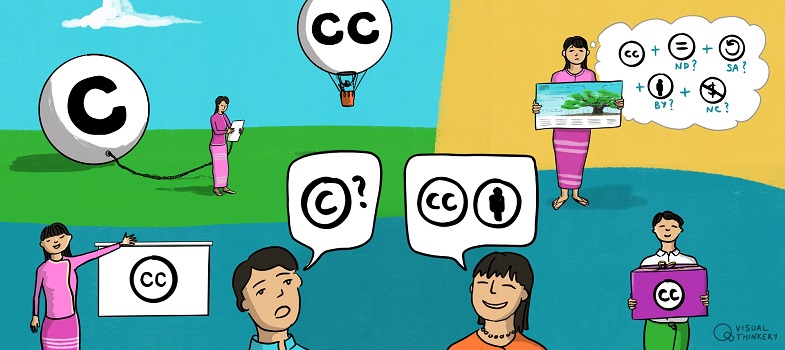

Inspired by the value of Eldred’s goal to make more creative works freely available on the internet, and responding to a growing community of bloggers who were creating, remixing and sharing content, Lessig and others came up with an idea. They created a non-profit organisation called Creative Commons and, in 2002, published the Creative Commons licences – a set of free, public licences that would allow creators to keep their copyrights while sharing their works on more flexible terms than the default ‘all rights reserved’.

As we saw in Unit 1, copyright is automatic, whether you want it or not. And while some people want to reserve all of their rights, many want to share their work with the public more freely. The idea behind CC licensing was to create an easy way for creators who wanted to share their works in ways that were consistent with copyright law.

From the start, Creative Commons licences were intended to be used by creators all over the world. The CC founders were initially motivated by a piece of US copyright legislation, but similarly restrictive copyright laws all over the world restricted how our shared culture and collective knowledge could be used, even while digital technologies and the internet have opened new ways for people to participate in culture and knowledge production.

Since Creative Commons was founded, much has changed in the way people share and how the internet operates. In many places around the world, the restrictions on using creative works have increased. Yet sharing and making changes to resources – that is, ‘remixing’ – are the norm online. Think about music tracks that comprise different pieces of existing music (sometimes called a mash-up), or even the photos your friend posted on Facebook last week. Sometimes this type of sharing and remixing happen in violation of copyright law. Sometimes they happen within social media networks that do not allow those works to be shared on other parts of the web.

Reflection

How often do you ask copyright owners for permission to share their material with colleagues and friends? Do you check whether you can reuse materials created by others?

In domains like textbook publishing, academic research, documentary film, and many more, restrictive copyright rules continue to inhibit creation, access and remix. CC tools are helping to solve this problem. In December 2019, Creative Commons licences were reported to have been used by more than 1.6 billion works online across 9 million websites. The grand experiment that started more than 15 years ago has been a success, including in ways unimagined by CC’s founders.

While other custom open copyright licences have been developed in the past, we recommend using Creative Commons licences because they are up to date, free-to-use, and have been broadly adopted by governments, institutions and individuals as the global standard for open copyright licences. They are also machine-readable, which means that material with a Creative Commons licence can be easily understood by applications, search engines and other kinds of technology. We will find out more about the different aspects of CC licensing in Section 3.1.

In the next section, you’ll learn more about what Creative Commons looks like today: the licences, the organisation and the movement.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA)