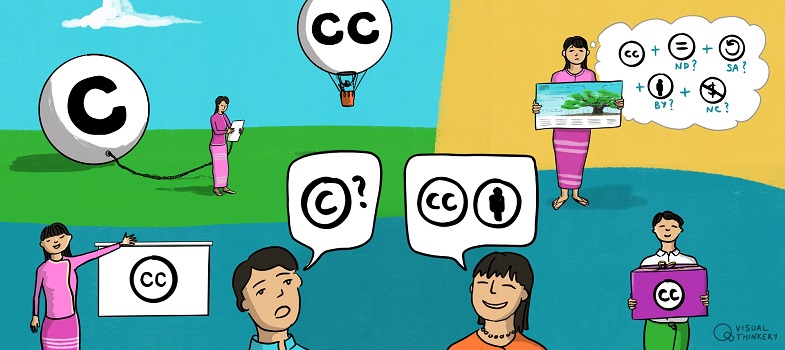

Copyright and Creative Commons

The statement that ‘Creative Commons licences are copyright licences’ tells you the following about them:

- Creative Commons licences ‘operate’, or apply, only when the work is within the scope of copyright law (or other related law) and the restrictions of copyright law apply to the intended use of the work. (This is discussed in more detail below.)

- Certain other rights (such as patents, trademarks, privacy and publicity rights) are not covered by the licences, and so must be managed separately.

The first statement explains a basic limitation of the licences in controlling what people do with the work. The second statement provides a warning that there may be other rights at play with the work that restrict how it is used.

Let’s start by unpacking what it means for the licence to apply where copyright applies.

Creative Commons licences are appropriate for creators who have created something protectable by copyright, such as an image, article or book, and want to provide people with one or more of the permissions governed by copyright law. For example, if you want to give others permissions to freely copy and redistribute your work, you can use a CC licence to grant them those permissions. Likewise, if you want to give others permissions to freely transform or alter your work, or otherwise create derivative works based upon it, you can use a CC licence to grant them those permissions.

However, you don’t need to use a Creative Commons licence to give someone permission to read your article or watch your video, because reading and watching aren’t activities that copyright generally regulates.

Two more important scenarios in which a user does not need a copyright licence are:

- when fair use, fair dealing or some other limitation and exception to copyright applies

- when the work is in the public domain – remember from Unit 2 that this depends on the law that applies to your use (where you are using the work) and the copyright law in that country.

Because users don’t need copyright licences in these scenarios, CC licences aren’t needed.

Can you think of reasons why someone might try to apply a CC licence to a work not covered by copyright in their own country? Or reasons why a CC licensor might expect attribution every time their work is used, even for a use that is not prohibited by copyright law?

A CC licensor might be trying to exert control they do not actually have by law. But more likely than not, they simply do not know that copyright does not apply or that a work is in the public domain. Or, for the savvy licensor, they may realise their work is in the public domain in some countries but not public domain everywhere, and they want to be sure everyone everywhere is able to reuse it.

One other subtle but important difference about the scope of CC licences is that they also cover other rights closely related to copyright, called ‘similar rights’. We introduced ‘similar rights’ in Section 1.2 when we looked at the new Myanmar Copyright Act. Just as with copyright, the CC licence conditions only come into play when similar rights otherwise apply to the work and to the particular reuse made by someone using the CC-licensed work.

The other critical part of the statement ‘CC licences are copyright licences’ is that there may be other rights in the works upon which the licence has no effect – for example, privacy rights. Again, CC licences do not have any effect on rights beyond copyright and similar rights as defined in the licences, so other rights have to be managed separately.

While not required, Creative Commons urges creators to make sure there are no other rights [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] that may prevent reuse of the work as intended. CC licensors do not make any warranties about reuse of the work. That means that unless the licensor is offering a separate warranty, it is incumbent on the reuser to determine whether other rights may impact their intended reuse of the work. Learning more can sometimes be as easy as contacting the licensor to inquire about these possible other rights. Read through this complete list of considerations for reusers of CC-licensed works.

What types of content can be CC-licensed?

You can apply a CC licence to anything protected by copyright that you own, with one important exception.

CC urges creators not to apply CC licences to software. This is because there are many free and open source software licences that do that job better because they were built specifically as software licences. For example, most open source software licences include provisions about distributing the software’s source code, and CC licences do not address that important aspect of sharing software. The software sharing ecosystem is well-established, and there are many good open source software licences to choose from. This FAQ from CC’s website has more information about why we discourage our licences for software.

Whose rights are covered by the CC licence?

A CC licence on a given work only covers the copyright held by the person who applied the licence: the licensor. That might sound obvious, but it is an important point to understand. For example, many employers own the copyright to works created by employees, so if an employee applies a CC licence to a work owned by her employer, she is not able to give any permission whatsoever to reuse the work. The person who applies the licence needs to be the creator, or someone who has acquired the rights.

Additionally, a work may incorporate the copyrighted work of another, such as a scholarly article that uses a copyrighted photograph to illustrate an idea (after having received the permission of the owner of the photograph to include it). The CC licence applied by the author of the scholarly article does not apply to the photograph; only the remainder of the work. Separate permission may need to be obtained in order to reproduce the photograph, but not the remainder of the article. (See Section 4.1 for more details on how to handle these situations.)

Also, works often have more than one copyright attached to them. For example, a filmmaker may own the copyright to a film adaptation of a book, but the book author also holds a copyright to the book that the film is based on. In this example, if the film is CC-licensed, the CC licence only applies to the film and not the book. The user may need to separately obtain a licence to use the copyrightable content from the book that is part of the film.

Introduction