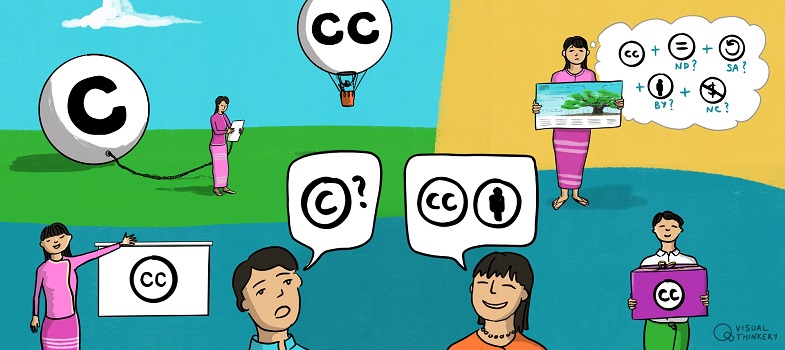

Distinguishing the licences

To really understand how the different options work, let’s dig into the different licence elements. Attribution is a part of all CC licences, and we will dissect exactly what type of attribution is required in a later unit. For now, let’s focus on what makes the licences different.

Commercial vs non-commercial use

As we know, three of the licences (CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA and CC BY-NC-ND) limit reuse of the work to non-commercial purposes only. In the legal code, a non-commercial purpose is defined as one that is ‘not primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or monetary compensation’. This is intended to provide flexibility depending on the facts surrounding the reuse, without over-specifying exact situations that could exclude some prohibited and some permitted reuses.

It’s important to note that CC’s definition of NC depends on the use, not the user. If you are a non-profit or charitable organisation, your use of an NC-licensed work could still run afoul of the NC restriction; if you are a for-profit entity, your use of an NC-licensed work does not necessarily mean you have violated the term. For example, a non-profit entity cannot sell another’s NC-licensed work for a profit, and a for-profit may use an NC-licensed work for non-commercial purposes. Whether a use is commercial depends on the specifics of the situation. Creative Commons’ NonCommercial Interpretation page [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] has more information and examples.

Adaptations

The other differences between the licences hinge on whether, and on what terms, reusers can adapt and then share the licensed work. As we saw in Unit 1, the question of what constitutes an adaptation of a licensed work depends on applicable copyright law. One of the exclusive rights granted to creators under copyright is the right to create adaptations of their works – or, as they are called in some places, derivative works. (For example, creating a movie based on a book, or translating a book from one language to another.)

As a legal matter, at times it is tricky to determine exactly what is and is not an adaptation. Here are some handy rules about the licences to keep in mind:

- Technical format-shifting (for example, converting a licensed work from a digital format to a physical copy) is not an adaptation, regardless of what applicable copyright law may otherwise provide.

- Fixing minor problems with spelling or punctuation is not an adaptation.

- Syncing a musical work with a moving image is an adaptation, regardless of what applicable copyright law may otherwise provide.

- In Units 4 and 5 we will look at different ways in which you might want to use CC-licensed materials. Reproducing and putting works together into a collection is not an adaptation of the individual works. For example, combining standalone essays by several authors into an essay collection for use as an open textbook is a collection and not an adaptation. Most open courseware is a collection of others’ open educational resources (OER).

- Including an image in connection with text – such as in a blog post, a PowerPoint presentation or an article – does not create an adaptation unless the photo itself is adapted.

Two of the NoDerivatives licences (BY-ND and BY-NC-ND) prohibit reusers from sharing (i.e. distributing or making available) adaptations of the licensed work. To be clear, this means anyone may create adaptations of works under an ND licence as long as they do not share the work with others in adapted form. Among other things, this allows organisations to engage in text and data mining without violating the ND term.

Two of the ShareAlike licences (BY-SA and BY-NC-SA) require that if adaptations of the licensed work are shared, they must be made available under the same or a compatible licence. For ShareAlike purposes, the list of compatible licences is short. It includes later versions of the same licence (so for example, BY-SA 4.0 is compatible with BY-SA 3.0) and a few non-CC licences designated as compatible by Creative Commons (such as the Free Art Licence). You can read more about this here, but the most important thing to remember is that ShareAlike requires that if you share your adaptation, you must do so using the same or a compatible licence.

Public domain

In addition to the CC licence suite, Creative Commons also has an option for creators who want to take a ‘no rights reserved’ approach and disclaim copyright entirely. This is CC0, the public domain dedication tool.

Like the CC licences, CC0 (read ‘CC Zero’) uses the three-layer design: legal code, deed and metadata.

The CC0 legal code also uses a three-pronged legal approach. Some countries do not allow creators to dedicate their work to the public domain through a waiver or abandonment of those rights, so CC0 includes a ‘fallback’ licence that allows anyone in the world to do anything with the work unconditionally. The fallback licence comes into play when the waiver fails for any reason. And finally, in the rare instance that both the waiver and the fallback licence are not enforceable, CC includes a promise by the person applying CC0 to their work that they will not assert copyright against reusers in a manner that interferes with their stated intention of surrendering all rights in the work.

Like the licences, CC0 is a copyright tool, but it also covers a few additional rights beyond those covered by the CC licences, such as non-competition laws. From a reuse perspective, there may still be other rights that require clearance separately, such as trademark and patent rights, and third party rights in the work, such as publicity or privacy rights.

Introducing the six licence types