This dialogue in the GIF below appeared in January 1966 scientific article written by the MIT Professor Joseph Weizenbaum. It appears to be a session between a patient and their sympathetic psychotherapist who went by the name ELIZA.

In actuality, ELIZA was one of the first examples of a chatbot

– a computer that engages in conversation with human beings. Wherever ELIZA was

demonstrated, it caused a sensation; Weizenbaum told a story of how one of his co-workers

engaged with the program:

My secretary, who had watched me work on the program for many months and therefore surely knew it to be merely a computer program, started conversing with it. After only a few interchanges with it, she asked me to leave the room.

Such was the excitement of seeing a computer actively participate in a conversation, to seemingly understand the patient and drive further discussion, that shortly after ELIZA’s introduction to the world a group of psychologists wrote:

Further work must be done before the program will be ready for clinical use. If the method proves beneficial, then it would provide a therapeutic tool which can be made widely available to mental hospitals and psychiatric centers suffering a shortage of therapists. Because of the time-sharing capabilities of modern and future computers, several hundreds of patients an hour could be handled by a computer system designed for this purpose. The human therapist, involved in the design and operation of the system, would not be replaced, but would become a much more efficient man since his efforts would no longer be limited to the one-to-one patient-therapist as now exists.

In actuality (as Weizenbaum was all too willing to explain to anyone willing to listen) ELIZA is a relatively simple program that recognises certain words and phrases entered by the user and uses it to generate one of a series of its own questions. It doesn’t matter if the user enters nonsense, ELIZA will still happily converse with them:

A quick

play with ELIZA almost always reveals its limitations and after a short time,

many people can begin to see how the program works – try it, you can play with

an online version of ELIZA

here.

However, to Weizenbaum’s surprise, ELIZA users remained deeply engaged by ELIZA - even when they knew how the chatbot worked! People were willing to spend hours conversing with the program as if it was an intelligent person. After observing her own students engage with ELIZA, the American sociologist Sherry Turkle created the term ‘The ELIZA Effect’ which she described as:

The susceptibility of people to read far more understanding than is warranted into strings of symbols—especially words—strung together by computer.

If a computer behaves in a manner that, in some way, resembles that of a human being; the ELIZA Effect says that we are much more likely to assume it is intelligent and has similar interests and emotions to humans.

ELIZA came towards the end of the first wave of research into artificial intelligence (AI). The idea of ‘thinking machines’ had long been a staple of science fiction, but serious research into the topic began in the mid-1940s, even before the invention of the digital computer. The term ‘artificial intelligence’ was created by the American mathematician John McCarthy, who in 1955 invited interested fellow countrymen to The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence the following summer.

The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.

This informal group

laid the foundations for the first, dazzling successes in artificial

intelligence. Within a few years, computers were playing games such as

draughts, solving word and logic problems; and promising to soon be able to

translate languages, convert speech to text and recognise faces.

This informal group

laid the foundations for the first, dazzling successes in artificial

intelligence. Within a few years, computers were playing games such as

draughts, solving word and logic problems; and promising to soon be able to

translate languages, convert speech to text and recognise faces.

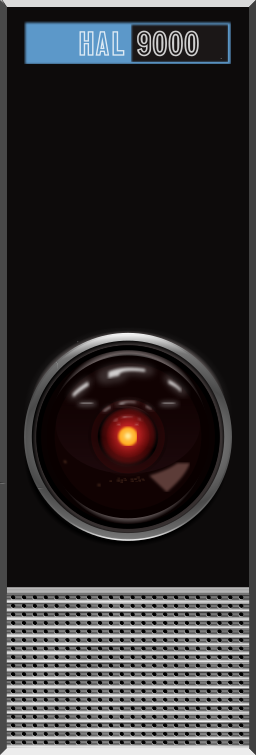

To these early pioneers, it seemed entirely reasonable to assume a machine capable of mimicking every aspect of human intelligence lay only twenty or years into the future. This optimism can still be seen in the popular fiction of the era: the 1950s and 1960s were the era of giant, intelligent machines, most famously Arthur C Clarke’s HAL 9000, the coolly, murderous villain of the science fiction classic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’.

‘Dave, I don’t know how else to put this, but it just happens to be an unalterable fact that I am incapable of being wrong.’

The capabilities of HAL were informed by Marvin Minsky, one of the attendees of the Dartmouth summer school; but even as the movie was in production, Minsky was about to end the early optimism into artificial intelligence.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews