5 Hard disk drives: a conversation

Timing

This section of the course should take you around two hours to complete.

Rupert was bored – he fiddled with his Rolodex and sighed deeply. It had been six weeks since he had solved his last case and no business had materialised since then. The mortgage payment was overdue, but at least he had caught up with his Open University module.

A sudden noise caught his attention – the street door of the dingy office complex had banged closed. Probably because of the draughts caused by lots of open windows, reasoned Rupert. No air-conditioning here and the temperature outside was close to 30 degrees.

Listening carefully now, Rupert followed the faint sound of footsteps to the second floor. He held his breath to the count of three after they stopped outside his office door. “Come in,” he said quietly and a bit too quickly, anticipating the knock. A young woman stepped through the door into the gloomy interior. Without invitation, she sank into the classy but tatty green leather chair next to the Art Deco desk. “Gloria,” she said, extending her hand in greeting. A silence followed. Rupert waited, patiently, knowing that saying less often means learning more. Nervously, she scanned the room before spotting the Rolodex (Figure 13). “What is that?” she asked.

“That,” said Rupert, “is my father’s Rolodex. It contains data about all of his clients over his entire career as a private investigator.”

“I have seen the term Rolodex used to mean the whole collection of an individual’s business contacts, but I never knew that there was such a thing as a real Rolodex,” said Gloria, showing her age.

“Yes, the state-of-the-art data management system for 1958, was the Rolodex,” replied Rupert. “They still sell them, you know, but they come with a maximum of 500 cards these days – not like the monsters of the old days that could hold several thousand cards.”

There was another short and uneasy silence.

“How do you store your data these days?”

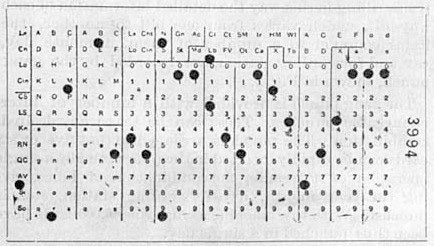

Rupert, sensing that this was some kind of test said, flatly, “I’ve moved on to punched cards!” (Figure 14).

Gloria looked aghast until Rupert relented: “Only joking! Seriously, I know all about data. I am taking a Level 1 Open University computing module. I have learned about databases and the different formats for storing numbers and text.”

“That’s a good start,” she replied. “I have a masters degree in digital data security, and I would like to move into digital forensics – you know, the branch of forensic science that is concerned with obtaining legal evidence from computer systems.”

“Do you mean computer forensics?” said Rupert.

“Yes, same thing. But let’s see how much you know already about the secrets that can be held in the data on a computer and how you can unlock them”, Gloria continued. “For example,

- Why does solid-state memory create a problem for digital forensics?

- When is deleted data not really deleted?”

Rupert looked down at his shoes, sheepishly. “I haven’t got that far in my module yet,” he admitted.

“The reason I am here is to make a proposition,” said Gloria, leaning towards him in a conspiratorial way. “I know how to find data in the guts of a computer. You are a private investigator who knows how people tick. Why don’t we work together?”