1 How to use this course

This course is a learning resource. Like all resources, there are different ways to use it depending upon what you are trying to achieve. You may be reading it as your only introduction to systems thinking or it may be the first part in a much larger course. You may simply be interested in knowing what others mean when they talk about systems or in using it as a route map to direct you to the wider world of systems thinking. Whatever you are trying to achieve it is important that you not only read the text thoroughly but also undertake the exercises. After all, this is a book about systems thinking and practice, and without practising your thinking you may not learn how powerful systems ideas can be. You can't get good at carpentry, or playing the piano, or driving a car simply by reading the books – you have to try out the ideas and techniques for yourself.

The exercises come in two types: Self Assessment Questions (SAQs) and Activities. SAQs test your understanding of the key concepts and ‘set’ answers are provided to compare your answers to. Activities examine how you think about situations you face using those same concepts. There are no ‘set’ answers to these Activities as they are personal to you. Indeed the best opportunities to practice will come whenever you're working with a situation and you realise that you don't quite understand it, or you can't quite see what to do, or you don't know if what you did before has helped – in other words, times when you are puzzled, intrigued or worried. These times are, for you, the equivalent of a field trip for a geologist, a visit to a gallery for an art historian, or gathering vital economic data to an economist. They provide the raw material with which you can work.

Some people seem to have a natural talent for systems thinking, just as some have a natural talent for playing the piano. But most people find it rather awkward and difficult at first. In a way, that is an encouraging sign; it shows that you are genuinely coming to grips with something unfamiliar; and, after all, there is no point in studying to learn what you already know. But it will require perseverance and you aren't expected to grasp it all straight away.

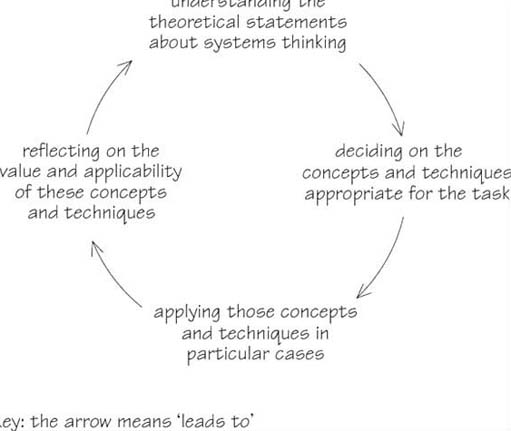

It is the interaction of theory and practice that brings knowledge and understanding of systems. The theoretical statements will lead you to practice certain concepts and techniques. And as you practice, and think about that practice, you will find yourself amending, refining and changing the theories with which you started. Those changed theories will then inform what you do next (see Figure 1). You can go round the cycle as often as you like. Each time you do, your ideas about systems will be more powerful, and your practice in working with them will be more effective.

However, learning by experience is not always simple. First, sometimes we don't learn from our experiences! Or, at least, we don't recognise the mistakes we make, or we learn the wrong lessons, and so don't do much better next time. It is usually easier to account for things going wrong in terms of what the other person did, or in terms of other external factors. Such explanations are usually at least partly true. The snag is that they may obscure ways in which we might have handled the situation differently.

Secondly, thinking about our own practice isn't something that most of us take seriously as a matter of course. Indeed, as far as much of our life is concerned, there are definite pressures that work against it. They spring from the distinctive characteristics of work and the increasing complexity of our lives. In particular, the pace, variety, fragmentation and interruptions of work make sustained thought about problems difficult. Superficial understandings and responses are one way of coping, and any deeper reflection feels like a luxury we cannot afford.

Lastly, you will learn a great deal more, and a great deal more quickly, if you are ruthlessly strict with yourself. If, for example, you draw a diagram and it doesn't seem quite right, you could suppress the feeling and press on. But there'll be huge dividends in stopping, trying to see what is wrong, drawing another version and so on until you are satisfied. To take another example, when you try to use the concept of a boundary, you may say to yourself it was quite useful even though it didn't reveal much. If you do that, you'll be missing what's interesting – why didn't it reveal much? Did you just repeat what you already knew? Did you start to see some of the implications and draw back from expanding them? Or, if you made genuine efforts, why do you think the concept wasn't useful in that particular case? The answer to any one of these questions will be far more valuable than an activity completed in a lifeless but ‘officially correct’ way.

If you follow these guidelines you will be well on your way to learning to learn – which is important for any subject you may want to study.