4.1 Thinking in systems

One of the difficulties facing newcomers to systems ideas is the notion that thinking about a topic or situation in a different way actually makes a difference. When confronted with a complex situation most people want to do something to solve it or change it; it is not part of everyday culture that simply thinking in a different way will help the situation.

One of the reasons why many people find difficulty with this idea is that the reductionist way of thinking has come to dominate our culture. This is a very powerful way of tackling problems, as witnessed by the successes of industrial technology in the realms of increasing levels of material production, well-being and comfort. So successful has this way of thinking become that there is a widespread, though often unrecognised, assumption that this is the best way to think about everything. Consequently reductionist methods are used in just about every academic discipline and in all aspects of life.

Although the reductionist way of thinking is a powerful one, it is, nevertheless, limited. There are situations in which the reductionist approach doesn't work. Reductionist methods cannot help to cope with problems that arise as a result of the complexity and interconnectedness between components in a system. Under these circumstances, any severing of the connections in order to make the situation simpler actually changes the situation. It's not too bad when one knows that the situation is caused by connectedness, but in many situations one isn't even sure of this, and one is certainly not sure which connections are significant and which are not. In these circumstances it is necessary to take the situation as a whole, and approaches which do this are termed holistic. One of the strongest characteristics of systems thinking is that it is holistic.

Thinking holistically does not mean that one cannot do anything to simplify the issue at hand. Owing to our inability to think of many things simultaneously, it is essential to simplify complex situations in some way like using multiple partial views in Section 3.5. A holistic approach emphasises that the simplification should be accomplished in a way that does not overlook the significant connectedness. There are two conclusions that follow directly from this.

Since in many situations we will not know which the significant connections and factors are, we should not expect our first attempt to analyse the situation to lead us to the best representation or ‘answer’. In general, we should expect to need several attempts at approaching the situation before gaining the confidence that we have identified the important features. This is in contrast to the reductionist approach, which usually presumes that there is one, and only one, right approach and right answer until proven otherwise. The holistic thinker will welcome techniques that generate many approaches, whereas the reductionist thinker will be looking for criteria for reducing the approaches to just one.

In order to simplify the situation without reducing the connectedness it will normally be necessary to reduce the level of detail in the representation. This will usually involve regarding the situation in a more abstract fashion. This is another strong characteristic of systems thinking – that in tackling an issue the first steps are to go up several levels of abstraction; the later stages involve ‘coming back down to earth’ (even using reductionist methods where appropriate) and relating the general conclusions reached to the specific issue in hand.

One way of representing complex issues more simply is by the use of diagrams. The use of diagrams to represent situations is an important theme of systems work, as connectedness can be simply represented and understood. (Text, like this, is essentially linear and emphasises just one order of connection.)

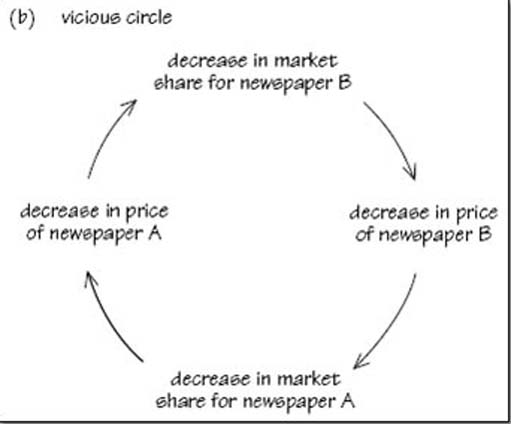

One of the central devices used in facilitating a holistic approach to problems is the representation of an issue or situation as system. Perceiving an issue as a system entails somehow representing the issue in such a way as to capture the essential connectedness of the issue. This requires the identification of boundary that separates the system from its environment and a method or device for representing the system (such as a diagram). Alternatively, it is possible to describe a system by analogy with a ‘standard system’ of some sort. At an abstract level a surprising number of systems seem to work in the same way. A readily understood ‘standard system’ is the ‘vicious circle’. Most of us have experienced vicious circles of one sort or another. For example, if I have an unproductive day, I tend to work late into the night to try and make up lost time. The next day, I'm tired out and even less productive. (Another example is shown in Figure 10(b) Vicious circle.)

It cannot be emphasised too much that the point of using the systems way of describing an issue is not to say ‘this is how it actually is’ but deliberately to generate variety in the way the issue is thought about. This variety is useful, indeed usually necessary, where our conventional or established way of thinking about the issue has not led to a satisfactory outcome.

The point of looking at something as if it were a system is to generate a new, yet adequately rich, representation of the issue so as to make it easy to think about in a new way. The only criterion for deciding whether a particular representation is a ‘good’ one or not, is whether it leads to fruitful insights. With practice, most people start to get the knack of being able to identify quickly two or three representations that all generate insights and new learning (as set out in the learning cycle shown in Figure 1 and an example of a virtuous circle), while beginners take longer and are pleased if they can get more than one.

Perhaps these remarks will make it clear why in this book I talk about ‘tools for thought’ and different approaches to the same issue. Everyone has his/her own ways of thinking about other people, conflict, power issues, organisational politics and so on, and, to the degree that these ways of thinking work, this is fine. The time when we all get stuck is when our usual ways of thinking about the issue totally let us down, when everything we try seems to make the situation worse, when every attempt to reduce conflict seems to increase misunderstandings, and so on. That is the time we need a ‘fresh approach’, a new way of looking at the whole thing, a new set of ideas to bring to the situation – and it is at such times that the systems approach can provide rewarding results. The systems approach to complex situations can also help in less extreme situations; indeed, if consistently used it would enable one to avoid getting into most extreme positions, because maintaining a flexible view of a situation allows one to anticipate and forestall unpleasant surprises sooner than someone who holds a fixed view.