Marsha P. Johnson

24 August 1945 – 6 July 1992 No pride for some of us without liberation for ALL of us.

Marsha P. Johnson was a black trans woman, LGBTQ+ activist and is reported to be one of the central figures (alongside Sylvia Rivera) of the historical Stonewall uprising in 1969. She also advocated for homeless LGBTQ+ youth as well as those affected by HIV and AIDS.

Marsha adopted her name when moving to New York and stated that the P stood for ‘Pay It No Mind’, a phrase that became her motto. Living in New York in the 1960s was difficult, with the state of New York still persecuting gay people and frequently criminalising their activities and presence.

The Stonewall Riots started on 28 June 1969 when police raided the bar in the early hours of the morning and started arresting mainly gay men. The LGBTQ community were fed up of continually being targeted and started to fight back. This protest lasted several days. Many eyewitnesses have identified Marsha as being one of the main instigators of this uprising.

The first gay Pride parade took place in 1970 and a series of gay rights groups emerged from this. Marsha was involved at the beginning of many groups but soon got frustrated by the exclusion of trans and LGBTQ+ people of colour from the movement. She spoke out about transphobia in the early movements and in 1970 with her friend Rivera founded Street Transvestite Actions Revolutionaries (STAR) which was described as ‘an organization dedicated to sheltering young transgender individuals who were shunned by their families’.

In 2019, New York City announced that Marsha along with Rivera would both be 2 out of 7 new monuments being built for NYC to include more historical women.

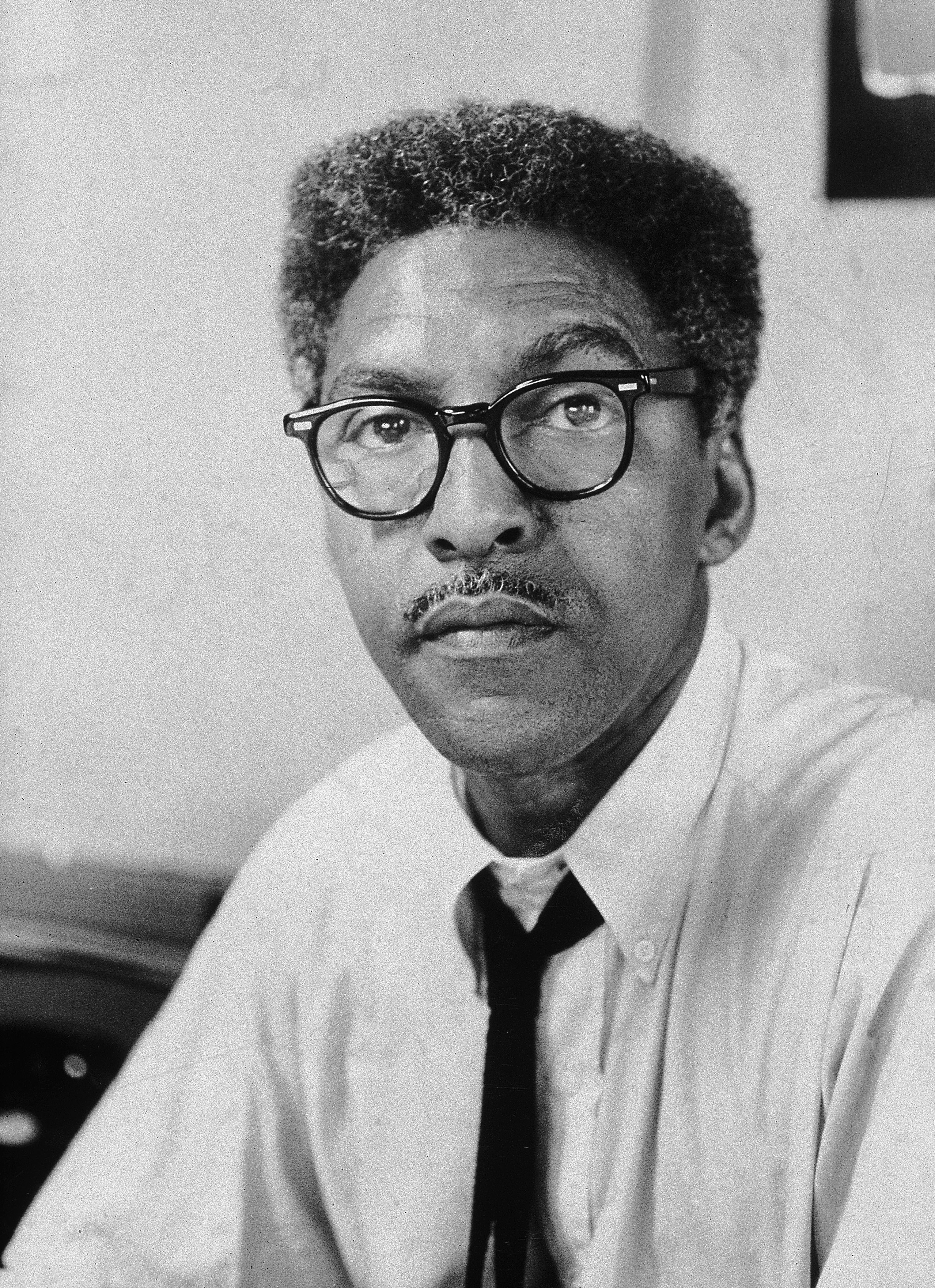

Bayard Rustin

17 March 1912 – 24 August 1987 Let us be enraged about injustice, but let us not be destroyed by it.

Bayard Rustin was a gay African American civil rights activist, who was an adviser to Martin Luther King Jr and the main organiser of the March on Washington in 1963.

Bayard practised non-violence in the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and was a leading activist in the early 1947–55 Civil Rights Movement. In 1953, he was arrested in California for homosexual acts and served 60 days in jail, had to resign from his role in FOR and sign up to the sex offenders’ register. However, despite this he still lived his life openly as a gay man.

This conviction nearly ruined his career, with many civil rights leaders publicly distancing themselves and forcing him to take a more ‘behind-the-scenes’ role.

He became a lead strategist for King between 1955 and 1968 and after the passage of the Civil rights legislation of 1964–5 got involved in other forms of activism and politics.

In 2013 he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama, who described him as ‘an unyielding activist for civil rights, dignity, and equality for all’, and who, as an openly gay American man, ‘stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights’.

In 2020 Bayard was pardoned for his 1953 conviction by California Governor Gavin Newsom, with the pardon describing him as ‘a visionary champion for peace, equality, and economic justice’.

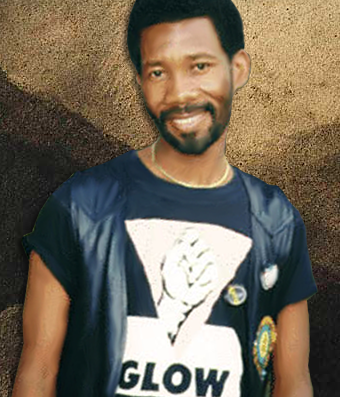

Simon Nkoli

26 November 1957 – 30 November 1998 I am black and I am gay. I cannot separate the two parts of me into secondary or primary struggles … So when I fight for my freedom I must fight against both oppressions. All those who believe in a democratic South African must fight against all oppression, all intolerance, all injustice.

Simon Nkoli was an activist for gay rights, AIDS and anti-Apartheid who strived for freedom and social justice in South Africa during the Apartheid struggle.

Simon had a difficult time coming out to his parents, and while they claimed to support him they attempted conversion therapy by bringing him to various religious leaders and psychiatrists, when he started a relationship with a man. It wasn’t until both families discovered that they had made a suicide pact that they were then permitted to be together.

Simon joined the Congress of South African Studies (COSAS) in 1980 and joined the fights against Apartheid. In 1983 he joined the Gay and Lesbian Association of South Africa (GASA) in an attempt to join up both sides of his activism. However, it was a predominantly white organisation and he found that GASA was firmly ‘apolitical’, disagreed with his anti-Apartheid work and would not support him on issues surrounding race.

He was arrested in 1984 with 20 other political leaders for organising a protest against rent increase, later called Delmas Treason Trial. They all faced the death penalty if convicted and during this time GASA kicked him out and refused to support him. In 1988 he was acquitted and founded the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW). He wanted a group that was not apolitical and was inclusive of non-white communities.

He was the first gay activist to meet with President Nelson Mandela and in 1990 he and Beverly Palesa Ditsie organised South African’s first ever Pride parade. He become one of the first gay men in the public eye to share that he was HIV positive and later died due to complications from illness.

Stormé DeLarverie

24 December 1920 – 24 May 2014

It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil

rights disobedience – it wasn’t no damn riot.

Stormé DeLarverie was a lifelong LGBT activist and drag performer who played an important role in the Stonewall rebellion in 1969, and while no one knows who threw the first punch it is believed it could have been her.

Stormé was never issued a birth certificate because her father was white and her mother was Black at a time when interracial marriage was illegal. She spent the 1950s and 1960s as the only ‘male impersonator’ in that time period, with her being the only woman in a group of 25 men. She was a massive fashion icon for many lesbians who started to feel comfortable wearing masculine clothes after seeing her walk around outside of a show in a suit.

At Stonewall, a scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs, who may have been Stormé, was roughly escorted to a police wagon. She kept escaping repeatedly and fought with many police officers who resorted to violence, using batons and handcuffs that were too tight. This woman was heard shouting ‘Why don’t you guys do something’ to the crowd when this was happening, which sparked the crowd into action.

Stormé was a member of the Stonewall Veterans Association and her role in the movement lasted long after 1969. She appointed herself guardian of lesbians in the Village. She held a state gun permit, patrolled the streets and checked lesbian bars, looking for abuse or harassment and keeping those there safe. She did this up until she was 80 years old.

Jackie Shane

15 May 1940 – 21 February 2019 I really feel that I made a place for myself with wonderful people. What I have said, what I have done, they say it makes their lives better.Jackie Shane was a black trans soul singer, who refused to live any other way than her authentic self, filled nightclubs in the 1960s and got a Grammy-nominated record in her 70s.

Jackie said she identified as a female from the age of 13 but throughout her career in the 1960s was publicly referred to as a man or in some cases mislabelled as a drag queen. Her family and close friends were reported to be very supportive of her gender identity.

During this period of time, when trans people were ‘universally vilified’, she was a courageous trailblazer for trans people, appearing on television in Nashville and Toronto when there were laws that more or less made her an outlaw.

Jackie started singing with Nashville Gospel Groups and performing on the radio when she was just a teenager. She then joined a travelling carnival and her success as a performer led to her sharing the stage with various soul legends and having a rich career in the 1960s.

Jackie only recorded one live album which was released in 1967 and reissued in 2015. She preferred the sound and power that came from live performances to studio tracks. She also consciously avoided the temptation of joining a big record label due to the fear of them trying to make her more mainstream and change her image to be more ‘male’ and therefore at that time more public friendly.

‘Any other way’, Jackie’s first full-length album, was released in October 2017 and was a collection of her previously unreleased hits. It was nominated for ‘Best Historical Album’ at the 61st Grammy Awards.

Gladys Bentley

12 August 1907 – 18 January 1960 It seems I was born different. At least, I always thought I was.

Gladys Bentley (stage name Bobbie Minton) was a top American blues singer and pianist during the Harlem Renaissance and a proud masc-presenting lesbian. She was a pioneer in pushing the boundaries of gender, sexuality, class and race.

She was born in Philadelphia and at age 16 left for New York City. Her big career break came when she became the main performer at Harry Hansberry’s Clam House, which was a popular gay speakeasy in Harlem. She made sure to openly include sexuality in her act with her songs, moves and attire. She was well known for performing in traditionally male clothing, including her signature white top hat and matching tuxedo.

She released eight singles of her music between 1928 and 1929 and the following year she had her own weekly radio programme. By the early 1930s, she was among the best-known black entertainers in the United States, headlining nightclubs and theatres and had created her own show that included men in drag.

The decade of the Great Depression severely impacted Harlem nightlife and forced her to move to LA where she mainly worked in gay clubs over the next decade. The restrictive climate of the 1950s made it very difficult to be a masc-presenting lesbian and in 1952 she published an essay saying that she had been made ‘cured’ of her lesbianism and was now married to a man and started wearing dresses. The validity of this could not be provided and many people believed it was an attempt to help restore her career.

Ernestine Eckstein

23 April 1941 – 15 July 1992 I think it takes a lot of courage. And I think a lot of people who would do it will suffer because of it. But I think any movement needs a certain number of courageous martyrs. There’s no getting around it. That’s really the only thing that can be done, you have to come out and be strong enough to accept whatever consequences come.Ernestine was a Black, lesbian and progressive activist. Born Ernestine Delois Eppenger she adopted the surname Eckstein to protect herself in both her work and personal life from those who might use her sexuality against her.

Her early life is filled with Civil Rights activism while studying for her degree, and after college she moved to New York City where she began attending meetings with one of the earliest gay rights organisations, the New York Mattachine Society. It was this move to New York that allowed her to come out as a lesbian to both herself and others and this in turn fuelled her passion for gay rights activism.

She is best known for being the only Black woman at the first gay and lesbian picket line in front of the White House in 1965. She carried a sign that said ‘Denial of Equality of Opportunity is Immoral’. Many LGBT people at the time opposed public protests.

A year after the White House picket she was the first Black woman to be on the cover of an iconic lesbian magazine called The Ladder, which was published by the lesbian political advocacy group the Daughters of Bilitis. One of the only sources of historical information on Ernestine’s life and her beliefs can be found in an 8-page interview that she did for the magazine. She later became a leader for the New York chapter of Daughters of Bilitis.

Ernestine was also an early activist in the Black feminist movement of the 1970s and was involved with the organisation Black Women Organized for Action.

Justin Fashanu

19 February 1961 – 2 May 1998

Justin was a British football player who was the first professional footballer to come out as gay. He first made headlines as a boxer for reaching two national finals and at the same time he was also making progress in the youth and reserve football teams for Norwich City Football Club, playing as a striker. He made his debut for the club’s first team at the age of 17. He played 103 matches for Norwich, scoring 40 goals. While at Norwich he was chosen for the under-21 England team.

In 1981 he transferred to Nottingham Forest, becoming the first Black footballer to be transferred with a fee of £1million, making him at the time the country’s most expensive Black player. It was a challenging time for him playing, with him encountering lots of homophobic and racist abuse.

Justin played professionally in North America for a short time and in 1990 he did an article for the British tabloid The Sun once he found out that a Sunday newspaper was about to expose his sexuality. It was published with the headline ‘£1m Soccer Star: I am Gay’. His brother John offered to pay him not to come out and described his brother as an ‘utter stranger’ when he did.

Justin then went on to have his most successful period in British football between 1991 and 1994, despite being mocked for being gay by opposing players and fans.

On 25 March 1998, Justin was accused of sexually assaulting a 17-year-old male. He was living in Maryland at the time when the age of consent was 16 but homosexual acts were illegal. The person who reported it said it was not consensual. He was questioned about it but not held in custody. The police later arrives with a warrant to arrest him but Justin had already left for England.

On the morning of 3 May 1998 he was found dead, hanged in a garage that he broke into in Shoreditch. In his suicide note, he denied the charges, stating that it was consensual and he fled to England for fear of not getting a fair trail for being Black and gay.

Reading list

Non-fiction

Modern Herstory, by Blair Imani

It’s About Damn Time, by Arlan Hamilton and Rachel L. Nelson

Wow, No Thank You, by Samantha Irby

Sister Outsider, by Audre Lorde

The Queen’s English, by Chloe O. Davis

Black on Both Sides, A Racial History of Trans Identity, by C. Riley

Snorton

The Days of Good Looks, by Cheryl Clarke

Bad Feminist, by Roxane Gay

Black. Queer. Southern. Women: An Oral History, by E. Patrick Johnson

Poetry

Black Girl, Call Home, by Jasmine Mans

Brown Girl Dreaming, by Jacqueline Woodson

HoodWitch: Poems, by Faylita Hicks

Don’t Call us Dead: Poems, by Danez Smith

Biographies and Autobiographies

Dear Senthuran, by Akwaeke Emezi

Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, by Audre Lorde

The Black Period, by Hafizah Augustus Geter

Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love and So Much More,

by Janet Mock

Fiction

The Good Luck Girls, by Charlotte Nicole Davis

The Broken Earth Trilogy, by N.K. Jemisin

The City We Became, by N.K. Jemisin

Elysium, by Jennifer Marie Brissett

Rainbow Milk, by Paul Mendez

The Stars and the Blackness Between Them, by Junauda

Petrus

Skye Falling, by Mia McKenzie

Vagabonds!, by Eloghosa Osunde

Memorial, by Bryan Washington

The Passing Playbook, by Isaac Fitzsimons

The Prophets, by Robert Jones Jr

Black Leopard, Red Wolf, by Marlon James

I’m So (Not) Over You, by Kosoko Jackson

Romance in Marseille, by Claude McKay

The Deep, by Rivers Solomon

Young adult

The Sound of Stars, by Alechia Dow

If It Makes You Happy, by Claire Kann

Let’s Talk About Love, by Claire Kann

Full Disclosure, by Camryn Garrett

This Is Kind Of An Epic Love Story, by Kacen Callender

Felix Ever After, by Kacen Callender

You Should See Me In A Crown, by Leah Johnson

The Summer of Everything, by Julian Winters

Legendborn, by Tracy Deonn

Cinderella is Dead, by Kalynn Bayron

Blood Like Magic, by Liselle Sambury

Skin Of The Sea, by Natasha Bowen

For children

Hurricane Child, by Kheryn Callender

King And The Dragon Flies, by Kacen Callender

Graphic novel

Bingo Love, by Tee Franklin

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews