Find out more about The Open University's Social Sciences courses.

What makes asking people from Black and minority ethnic communities about their origin so offensive? In recent years this basic expression of interest seems to have been behind a host of conflict, upset and tumultuous argument. Some say the question is simply a harmless expression of curiosity, a basic demonstration of interest borne of good social etiquette. On the other hand, reports suggest the enquiry can be condescending, a racial insult and an underhanded slur, barbed with rejection. While more and more people recognise that probing into racial origin may lead to offence (Harrison & Tanner, 2018), the reasons behind affront are infrequently discussed. Should you never ask people of colour where they come from? Does this apply to conversations with all minority ethnic groups? Why can the question lead to such an eruption of emotion and why is opinion so divided?

Writing as a Black British Psychotherapist, with a background in psychology, I explore the backdrop to these divided perspectives. I draw on knowledge gained in professional training as well as my own personal experience in the hope that insider perspective can illustrate the points and assist reflection.

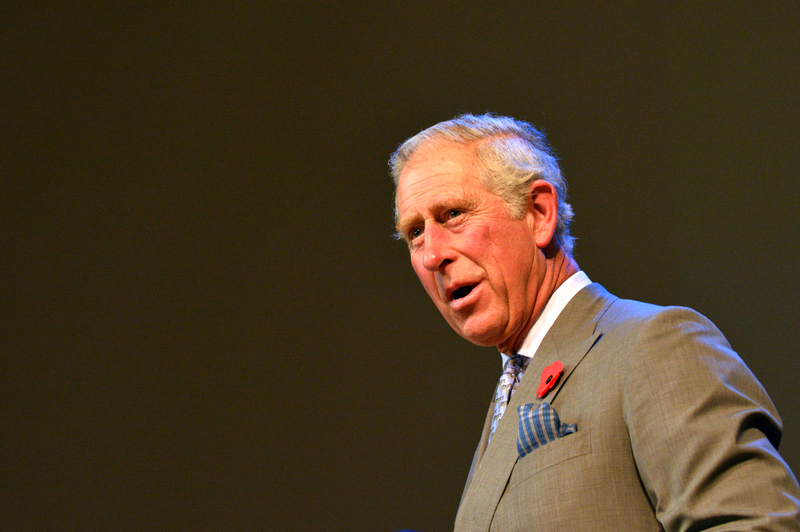

Racism rows reach royalty

King Charles IIIPerhaps the most widely reported incidents around this topic involve the

British Royal Family and Buckingham Palace. In 2017 Prince Charles made media headlines

after asking writer Anita Sethi where she was from at the 2017 Commonwealth People’s Forum in London. When she replied that she was from Manchester, UK, the then Prince chuckled and replied, ‘Well you don’t look like it’. He was hurriedly ushered away and Anita, whose mother came to England from British Guiana to work as a nurse (following ancestral indentureship), and father settled in England after Kenya was decolonised, said she’d felt shocked, humiliated and insulted, stressing that she was in fact very representative of the area in Manchester that she lived and had grown-up in.

King Charles IIIPerhaps the most widely reported incidents around this topic involve the

British Royal Family and Buckingham Palace. In 2017 Prince Charles made media headlines

after asking writer Anita Sethi where she was from at the 2017 Commonwealth People’s Forum in London. When she replied that she was from Manchester, UK, the then Prince chuckled and replied, ‘Well you don’t look like it’. He was hurriedly ushered away and Anita, whose mother came to England from British Guiana to work as a nurse (following ancestral indentureship), and father settled in England after Kenya was decolonised, said she’d felt shocked, humiliated and insulted, stressing that she was in fact very representative of the area in Manchester that she lived and had grown-up in.

On making headlines, journalists questioned the heir to the throne’s fitness for the role of monarch. Branded as out of touch with modern Britain he was dubbed as lacking understanding of UK’s colonial past, including the way that evidence of identity, origin and ancestry had been callously destroyed by colonisers (Sethi, 2018).

Ngozi Fulani (centre left) at a reception at Buckingham Palace, London on 29/11/22.

Ngozi Fulani (centre left) at a reception at Buckingham Palace, London on 29/11/22.

Four years later in November 2022 the monarchy was back in the headlines for a similar event, following persistent questioning on the origin of charity boss Ngozi Fulani by Buckingham Palace Aide Susan Hussey. The palace, hosting the reception in honour of those who work in and around domestic abuse, invited Ngozi who was representing ‘Sistah Space’, a not-for-profit that she had co-founded to support Black women who had suffered from domestic and sexual abuse. Moving Ngozi Fulani’s hair so she could better see her name badge, Lady Hussey began questioning. Responding that she came from Hackney and was born in London all proved to be unsatisfactory answers in a conversation which went like this:

Lady Hussey: Where are you from?

Ngozi Fulani: Sistah Space.

Lady Hussey: No, where do you come from?

Ngozi Fulani: We're based in Hackney.

Lady Hussey: No, what part of Africa are you from?

Ngozi Fulani: I don't know, they didn't leave any records.

Lady Hussey: Well, you must know where you're from. I spent time in France. Where are you from?

Ngozi Fulani: Here, the UK.

Lady Hussey: No, but what nationality are you?

Ngozi Fulani: I was born here and am British.

Lady Hussey: No, but where do you really come from? Where do your people come from?

Ngozi Fulani: 'My people?' Lady, what is this?

Lady Hussey: Oh, I can see I'm going to have a challenge getting you to say where you're from. When did you first come here?

Ngozi Fulani: Lady! I am a British national. My parents came here in the 50s.

Lady Hussey: Oh, I knew we'd get there in the end. You're Caribbean.

Ngozi Fulani: No lady, I am of African heritage, Caribbean descent, and British nationality.

Lady Hussey: Oh, so you're from ...

The furore that followed led to the apology and resignation of Lady Hussey, a longstanding friend of Queen Elizabeth II and Godmother to Prince William. Ngozi Fulani said she felt trapped and abused during the interaction, which seemed like an interrogation and as if Lady Hussey ‘had wanted her to denounce her citizenship’. She explained that although she had later tweeted about the interaction, she had not provided the name of the person who the exchange had occurred with and certainly did not want them to lose their position over it.

The changing face of racism

Lady Susan Hussey (Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Elizabeth II)Events around the case, escalated quickly. Eyewitnesses described Lady Hussey’s questioning as ‘offensive, racist and unwelcoming’. The Palace issued a statement saying the incident was ‘unacceptable and deeply regrettable’ adding that racism had no place in British society. The days that followed saw social media awash with claims that Ngozi Fulani was seeking attention, had been overly sensitive or had deliberately tried to entrap the Palace by wearing her hair in locs and dressing in African costume which would obviously stimulate questions about where she came from. She later reported a week of horrific online abuse, after members of the public slated her for trying to bring down the British monarchy, criticised her for taking an African name over her birth name Marlene Headley and accused her of racism for working specifically with Black women. Ngozi’s critics were Black as well as White, which counters the argument that this was something that White people just didn’t understand. Nana Akua, a Black female presenter on Sky News, for example, condemned Ngozi, deprecating her dress by saying ‘forget where you come from in Africa, more like, what planet, what is going on with her hair, seriously I have some bad wigs that I wear to get a reaction but that is another level’ (Akua, 2022). Just over a week later, Sistah Space was forced to temporarily close, in order to maintain the safety of both staff and service-users. Reports of a later conciliatory meeting between Fulani and Hussey were accompanied by news that the Charity Commission had begun investigating Sistah Space due to queries raised by an anonymous user challenging the way that the Charity used funds.

Lady Susan Hussey (Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Elizabeth II)Events around the case, escalated quickly. Eyewitnesses described Lady Hussey’s questioning as ‘offensive, racist and unwelcoming’. The Palace issued a statement saying the incident was ‘unacceptable and deeply regrettable’ adding that racism had no place in British society. The days that followed saw social media awash with claims that Ngozi Fulani was seeking attention, had been overly sensitive or had deliberately tried to entrap the Palace by wearing her hair in locs and dressing in African costume which would obviously stimulate questions about where she came from. She later reported a week of horrific online abuse, after members of the public slated her for trying to bring down the British monarchy, criticised her for taking an African name over her birth name Marlene Headley and accused her of racism for working specifically with Black women. Ngozi’s critics were Black as well as White, which counters the argument that this was something that White people just didn’t understand. Nana Akua, a Black female presenter on Sky News, for example, condemned Ngozi, deprecating her dress by saying ‘forget where you come from in Africa, more like, what planet, what is going on with her hair, seriously I have some bad wigs that I wear to get a reaction but that is another level’ (Akua, 2022). Just over a week later, Sistah Space was forced to temporarily close, in order to maintain the safety of both staff and service-users. Reports of a later conciliatory meeting between Fulani and Hussey were accompanied by news that the Charity Commission had begun investigating Sistah Space due to queries raised by an anonymous user challenging the way that the Charity used funds.

Defenders

of Hussey, aged 83, argued that many older people were unaware of the social

moirés associated with modern multi-cultural society and that there was no

racism or malintent in her actions. The palace was described as cruel for

removing Lady Hussey from post after longstanding dedication and friendship.

Some of the disparity in views is likely to have something to do with societal shifts over time. It was not so long ago, for example, that accusations of racism equated with blatant, ‘plain to see’ overt prejudice. Physical attacks, verbal abuse, hate speech and legislation bound up in bias and discrimination was commonplace. In the 1950s, for example, Caribbean immigrants invited to the UK were still met with signs clearly stating: No Blacks, No Dogs and No Irish. Far-right politics in the meantime made work, health, and general living as impossible as finding accommodation. It was as recent as 1976 before legislative acts did so much as to encourage equality in basic environments such as the workplace, housing, and public services. The tightening of these equality laws saw attitudes associated with difference and inequality expressed in more subtle ways, however the recency of direct expressions of racism means that many may interpret more insidious acts of racism, such as those experienced by Ngozi, as relatively insignificant.

Birth of microaggression

Chester Pierce coined the term ‘microaggression’ in the late 1960s to describe verbal racial insults and put-downs that were issued by non-White Americans to African Americans via this more subtle expression of prejudice. Sue et al. (2007) later refined the definition and recognised the microaggression as a way of behaving that went beyond race. Sue described microaggression as: ‘the everyday slights, indignities, put downs and insults that people of colour, women, LGBT populations or those who are marginalized experience in their day-to-day interactions with people’ (Sue, 2015). Sue initially identified three broad types of microaggression which go some way in helping to categorise these offences:

Shifts in attitude and tolerance may make it hard for some people to understand the intensity of upset associated with this more subtle form of racism. It may be difficult to accept that another person can hurt without (i) a physical wound which can be seen or (ii) an emotional wound which has never been experienced. It can be difficult to understand that people’s feelings are individual, real and significant.Understanding feelings and emotions

Ngozi was criticised for being oversensitive and attention seeking, but it is worthwhile thinking about what these labels mean. Terms like ‘over-sensitivity’ for example are more about issuing judgement than they are about describing an objective state. An individual who is sensitive to something behaves so for a biological or historical reason; similarly an individual who is attention seeking is doing it to satisfy a need for attention which a broad-brush put-down is likely to make worse. In getting to grips with these labels, society could do a better job at helping us understand the nature of these psychological concepts. Emotions and feelings drive behaviour, are essential to maintaining good relationships and have close connection with mental health and wellbeing. Emotions stem from key structures in the limbic system of the brain and stimulate chemical reactions in our body. They are essentially unconscious processes designed to promote survival in instances where circumstances are too critical to leave responses to conscious decision making. Examples of primary emotions are fear, anger, joy, disgust and surprise. Being key to existence, emotions are universal and part of our essential biological make-up.

Ngozi was criticised for being oversensitive and attention seeking, but it is worthwhile thinking about what these labels mean. Terms like ‘over-sensitivity’ for example are more about issuing judgement than they are about describing an objective state. An individual who is sensitive to something behaves so for a biological or historical reason; similarly an individual who is attention seeking is doing it to satisfy a need for attention which a broad-brush put-down is likely to make worse. In getting to grips with these labels, society could do a better job at helping us understand the nature of these psychological concepts. Emotions and feelings drive behaviour, are essential to maintaining good relationships and have close connection with mental health and wellbeing. Emotions stem from key structures in the limbic system of the brain and stimulate chemical reactions in our body. They are essentially unconscious processes designed to promote survival in instances where circumstances are too critical to leave responses to conscious decision making. Examples of primary emotions are fear, anger, joy, disgust and surprise. Being key to existence, emotions are universal and part of our essential biological make-up.

Feelings on the other hand are the way that emotions are experienced. They relate to the sensations that are felt and develop according to environmental conditions, which mean they differ and create variation between individuals. Feelings emerge as a learned response to emotional triggers in the environment. Family practices, cultural and religious traditions, biological disposition and personal experience all influence how we feel as well as the intensity with which that feeling is felt. We operate in a world where these variations are on display, but we may not stop to think about it, in everyday life. People have different levels of tolerance to pain for example, and while one person may fight in a given situation another will tend to flee.

In basic terms, feelings arise as a result of chemicals, hormones and neurological responses that have been developed to help us navigate the world around us. To that extent, they are less likely to be under conscious control. Although we may sometimes be able to supress or control the behaviour arising from a feeling, we have little control over the emergence or intensity of the feeling itself. American Sociologist Bonilla-Silva writes extensively on racialised emotions, explaining that the process of being racialised or gendered involves a felt reaction to the way others treat you (Bonilla-Silva, 2019). These socially constructed concepts gain life through subjective experience, so pains felt by victims may seem quite innocuous to the perpetrator who may act consciously or unconsciously.

It is all too easy to say that somebody is ‘being silly’ or ‘being over-sensitive’ or ‘attention seeking’ when we don’t have their background, biology or experience.

Belonging, self-identify and inclusivity

Most people recognise that it might be unsettling to be persistently asked where you are from and then to have your response denied and disbelieved, but there is sometimes difficulty in understanding the strength of feeling in reaction to events. This is likely to be behind some of the accusations hurled at sufferers, describing them as attention seeking or overly sensitive. In reporting her experience, Ngozi was portrayed as being petty. Following the Buckingham Palace race row (as it was described by the media), many members of the public took to the internet to declare how pleased they were when asked where they came from. Some said that rather than call racism, Ngozi should have taken the enquiry as a compliment.

These comments take little account of the way that people develop feelings. For many people of Black and minority ethnic origin in white-majority spaces, racial background has been used to highlight variation from the norm resulting in them having to navigate isolating, humiliating, ridiculing and demeaning circumstances over the breadth of a lifetime. Harrison & Tanner, (2018, p. 4) aptly use the analogy of being poked in a particular spot by many people over a stretch of time in order to convey this idea. The person poking may have good reason for their prods or may not even know they are doing it, nevertheless the spot being poked develops a problem through repeated injury, perhaps visible as a bruise or a sore.

Training as a mental health practitioner has helped me understand how repeated small events can accumulate and have a major impact on physical health and mental wellbeing. Society has developed in a way that makes it easier to understand that we need to treat physical wounds with care, but less consideration is given to psychological wounds which, in the main, tend to be invisible. There is significant neurological evidence to suggest that psychological wounds leave mental scars which in essence help make up our personality (Solms, 2018). I describe these psychological wounds as psychic corns, that is, areas of the mind that through repeated injury have developed a protective callus, but which are also sensitive to touch. In the context of the Buckingham Palace Race Row, had Lady Hussey been satisfied with Ngozi Fulaney’s first couple of responses the callus would have protected and minimised hurt. Persistent enquiry however depressed the corn sufficient for Ngozi to feel trapped and abused. Similarly, Anita in conversation with the then Prince Charles at the 2017 Commonwealth Peoples forum, felt shocked, humiliated and insulted.

Group membership, a feeling of belonging and having our feelings recognised are important aspects of psychological wellbeing. If multi-cultural societies are to be effective, marginalised communities need to feel included as well as represented. In many instances this requires re-education, since the views and perspectives of these groups are not well reflected in western society. Like many UK institutions, Buckingham Palace in its efforts to modernise, invited Black and Brown people to events, but need to do much more work on how to ensure their events are inclusive. This involves better understanding of the part that the British Empire played in establishing promoting colonial systems and structures, as well as the part that they continue to play in maintaining and reinforcing its legacy effects.

British national of African heritage and Caribbean descent

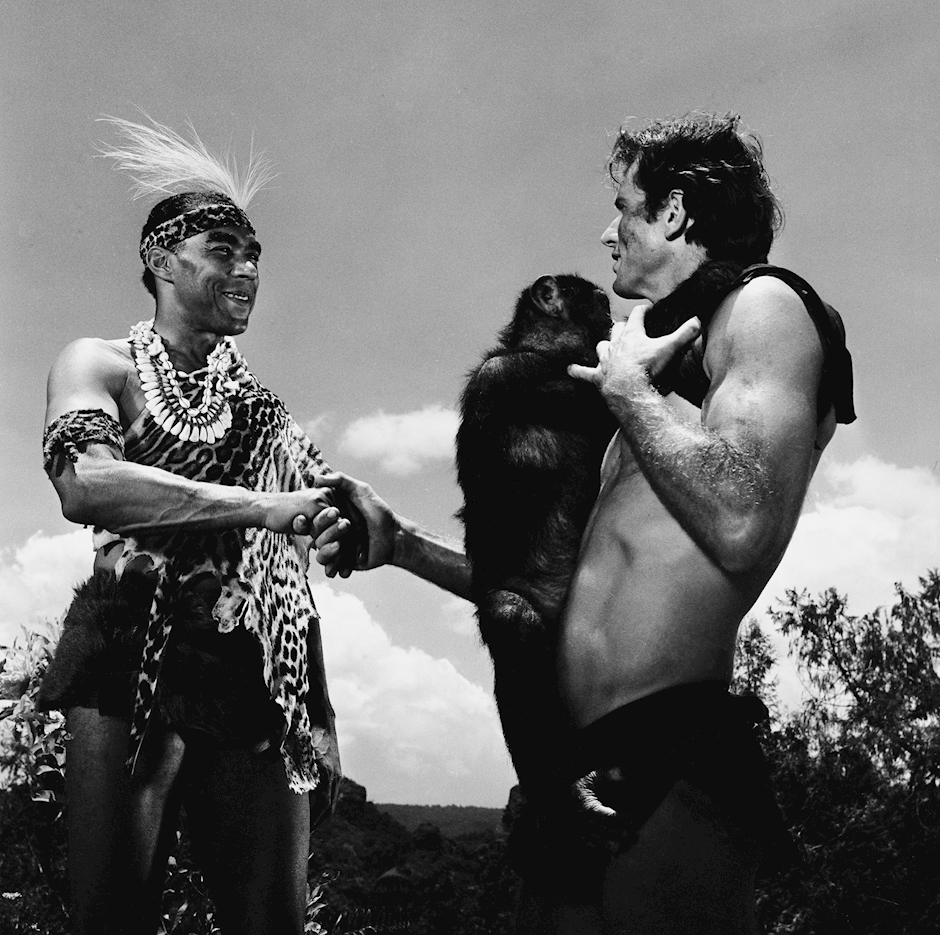

Woody Strode as Jamayo and Ron Ely as Tarzan.Like Ngozi, I am a Black British National of African heritage and Caribbean descent. I identify with the feelings she has expressed. As a White person if humiliated, I imagine I would have blushed at the embarrassment caused by the repeated questioning of my racial origin and this might have given a clearer indication of my growing discomfort, but words have not been coined to describe my inner flush. When it happens, hurt associated with questioning of my racial origin, or touching of my hair by a White person builds on a complex web of feelings. This is despite being married for over 30 years to a White British person. My feelings are coloured by early memories of my White friends in the playground recoiling with revolt, doubling up with laughter and telling me my hair was sticky and greasy or wiry and coarse to the touch. I don’t remember clearly, but it’s possible that after a while I agreed. I do remember being about seven years old and doing a school cultural activity when we were asked to talk about our family background. Stating that I was born in Mother’s Hospital in Hackney in London didn’t go down well. My teacher had said ‘no, where are your family from?’. I’d responded ‘Antigua’ only to be met by a round of laughter and many of my classmates shouting, ‘that’s not a country’. Apparently not many of my White classmates had heard of Antigua in the late 1960s. To tell the truth, I had never seen a photograph, painting or other image and the island was never mentioned on television or in the wider world. Only my family and family friends talked about it. For all I knew it was in their imagination. This place mum lamented on, called Antigua, with its glowing golden sand, crystal water and blue skies, sounded a bit like a Disney cartoon. Perhaps you mean ‘your family come from Jamaica’ my teacher had said, that’s in the Caribbean. Eager to move on, I had agreed, but that left me in a sticky position when a friend with Jamaican parents asked me where about in Jamaica my family had come from. Since I hadn’t been educated on any regions of Jamaica, I wasn’t able to answer and she giggled and called me a liar, which was true. I had realised at this early age, that going forward there was no answer to this question that would ever suffice. Over the next few years, in every white space at least one person would say ‘I know – you’re from – Jamaica’. In most instances I acquiesced, Jamaica was at least a place that people had heard of.

Woody Strode as Jamayo and Ron Ely as Tarzan.Like Ngozi, I am a Black British National of African heritage and Caribbean descent. I identify with the feelings she has expressed. As a White person if humiliated, I imagine I would have blushed at the embarrassment caused by the repeated questioning of my racial origin and this might have given a clearer indication of my growing discomfort, but words have not been coined to describe my inner flush. When it happens, hurt associated with questioning of my racial origin, or touching of my hair by a White person builds on a complex web of feelings. This is despite being married for over 30 years to a White British person. My feelings are coloured by early memories of my White friends in the playground recoiling with revolt, doubling up with laughter and telling me my hair was sticky and greasy or wiry and coarse to the touch. I don’t remember clearly, but it’s possible that after a while I agreed. I do remember being about seven years old and doing a school cultural activity when we were asked to talk about our family background. Stating that I was born in Mother’s Hospital in Hackney in London didn’t go down well. My teacher had said ‘no, where are your family from?’. I’d responded ‘Antigua’ only to be met by a round of laughter and many of my classmates shouting, ‘that’s not a country’. Apparently not many of my White classmates had heard of Antigua in the late 1960s. To tell the truth, I had never seen a photograph, painting or other image and the island was never mentioned on television or in the wider world. Only my family and family friends talked about it. For all I knew it was in their imagination. This place mum lamented on, called Antigua, with its glowing golden sand, crystal water and blue skies, sounded a bit like a Disney cartoon. Perhaps you mean ‘your family come from Jamaica’ my teacher had said, that’s in the Caribbean. Eager to move on, I had agreed, but that left me in a sticky position when a friend with Jamaican parents asked me where about in Jamaica my family had come from. Since I hadn’t been educated on any regions of Jamaica, I wasn’t able to answer and she giggled and called me a liar, which was true. I had realised at this early age, that going forward there was no answer to this question that would ever suffice. Over the next few years, in every white space at least one person would say ‘I know – you’re from – Jamaica’. In most instances I acquiesced, Jamaica was at least a place that people had heard of.

Since I didn’t know what the Caribbean looked like, it didn’t help that Tarzan King of the Jungle featured quite so heavily during my school years. A series of books and films released throughout the 1960s depicted Tarzan as the white skinned aristocrat who, orphaned in Africa as a child, brought civilisation and order to cannibal tribes in the jungle. These were people that boiled their own people in giant pots, depicted as savage and stupid, cartoon cut-outs without a modicum of roundedness or character.

These damaging stereotypes were peak time viewing at a time when there were few people of colour on television. They formed the basis of playground games, with the negative imagery being reinforced by programmes like the Black and White Minstrels where White people blacked up to look like gollywogs, and feature film Westerns in which the Indians were demonised, the White cowboys were the saviours, and the White woman represented the desirable.

September 1931: Minstrel show performers Alexander and Mose.

September 1931: Minstrel show performers Alexander and Mose.

Nothing positive was ever shared with me about Africa so it wasn’t received well when children at school or strangers on the street started telling me to go back there. It sounds strange now, but I wasn’t ever taught about my African ancestry, so these comments initially seemed strange, unfair, and unjust. Connecting with my African past is something I have had to work for in my adulthood. I can’t count the number of times a discussion or argument would end with somebody telling me to ‘go back to where I came from’ and the exchange would be peppered with put downs where I’d be called ‘a jungle bunny’ or uncivilised. For most of my childhood I don’t think I understood where people were telling me to go back to, but there was a definite feeling of never being safe or quite at home. At any moment I could be taunted by the crowd, rejected from a group, or abandoned by peers. As a child, it is not something I associated with race, it is just something that happened to me sometimes. It was only on reflection, after discussions occurred in groups and after I came across books that showed what was happening that I began to understand.

As an adult and psychotherapist, I can see how these situations contribute to post traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) where the nervous system remains prepared for attack in the hope of survival. This type of PTSD falls into the category of complex PTSD where trauma takes place in a variety of ways and is experienced over a long period of time, often commencing in early childhood. Triggers later in life can result in a rush of old feelings, such as dissociation, anger, headaches, dizziness and the need to get away. In this context Ngozi’s description of feeling ‘trapped, shocked and abused’ seem more understandable.

Antigua. Image: courtesy of the author who took it herself on a recent vist.Like Ngozi, I am a British national, of African heritage and Caribbean descent. My Caribbean mother made sure that my siblings and I fully understood the advantages that we had been afforded by being brought up in Britain. Contrasts between my own childhood and hers were never far from mouth. It was surprising to me then that my elder sister who came to the country with my mother during the Windrush period when she was three, was asked to prove her eligibility to live here. She needed to take a citizenship test and conjure up documentation to show that she had lived in the UK for all of the 60 years that she had been here. It was a really stressful time and led many in the Caribbean community to feel that they were not welcome here. Memories of this Windrush scandal return to mind when I pressed on where I am from. Other things that make this question difficult include not knowing where I do come from. Although I’ve spent hours poring over the internet, am registered with three DNA companies and travelled to Antigua to try and find out what part of Africa my ancestors were taken from, or what my family name might have been prior to having it quashed by that of my family’s plantation owners, I am no wiser with regards to where I come from or where I belong.

Antigua. Image: courtesy of the author who took it herself on a recent vist.Like Ngozi, I am a British national, of African heritage and Caribbean descent. My Caribbean mother made sure that my siblings and I fully understood the advantages that we had been afforded by being brought up in Britain. Contrasts between my own childhood and hers were never far from mouth. It was surprising to me then that my elder sister who came to the country with my mother during the Windrush period when she was three, was asked to prove her eligibility to live here. She needed to take a citizenship test and conjure up documentation to show that she had lived in the UK for all of the 60 years that she had been here. It was a really stressful time and led many in the Caribbean community to feel that they were not welcome here. Memories of this Windrush scandal return to mind when I pressed on where I am from. Other things that make this question difficult include not knowing where I do come from. Although I’ve spent hours poring over the internet, am registered with three DNA companies and travelled to Antigua to try and find out what part of Africa my ancestors were taken from, or what my family name might have been prior to having it quashed by that of my family’s plantation owners, I am no wiser with regards to where I come from or where I belong.

National Windrush Monument by Basil Watson, Waterloo Station.

National Windrush Monument by Basil Watson, Waterloo Station.

Psychological wellbeing and mental health

The covert nature of microaggressions can make them seem minor. However, research shows that it is just as important to address covert racism as it is to address overt racism. Contributing to a hostile culture in the classroom as well as the workplace, high instances of microaggressions correlate with poor educational outcome and create barriers to employment, career progression and staff retention (Gordon & Johnson, 2003; Harrison & Tanner, 2018). Further still, microaggressions and other covert forms of racism have been shown to be associated with negative emotional and physical health outcomes, including low self-esteem, depression, suicidality, body mass, hypertension and heart attack (Nadal, 2018; Sue et al., 2007; Williams, 2020).

Microaggressions are part of the integral fabric of modern-day society, with racist thoughts, attitudes and behaviour being inadvertently transmitted through regular day-to-day activity. As a result, it is not unusual for racial microaggressions to be perpetrated by racial minorities as well as White people (Allen, 2010). This is demonstrated in a range of studies, but can also be observed, in the Nana Akua online videos for example or Kemi Badenoch’s denial of White privilege and slamming of critical race theory. Microaggressions are a legacy of both systemic and internalised oppression and are perpetrated both consciously and unconsciously. Making ourselves aware of when and how they can occur is a duty that we all have.

Calling out racial microaggressions and other forms of covert racism often results in victims themselves being further persecuted. Ngozi Fulani is a prime case. Although she had no hand in Lady Hussey’s removal from post, she was subject to a hoard of online abuse and it was her, her organisation and the Black women suffering from domestic violence that were made to pay as a result of her sharing what had happened.

We might ask why Lady Hussey ended up resigning from her voluntary position. Perhaps the palace and newly appointed King had felt that there was a need to show support for stamping out racism after his own blunder with Anita Sethi just a few years before. However, penalising the perpetrator, Lady Hussey in this case, did not gain public sympathy, and sent out what is in essence an unhelpful message about how to address systemic racism effectively. Penalties give rise to hurt, anger and defensiveness, particularly when the perpetrator is uncertain or totally unaware of what they have done wrong. A better outcome would arise from a non-judgemental environment, which is what we strive for in the therapeutic space. This is an environment where both victim and perpetrator perspectives can be considered and where the interaction that takes place can be looked at with an objective lens. This is where understanding can be fostered and learning, and change can take place. A more effective intervention then would have been for the palace to educate its members, staff and associates. The web is littered with organisations that could provide this type of service and Sistah Space themselves could probably recommend or tailor a workshop to suit. Many organisations may then have followed that model.

Those at the head of all our British institutions need to be challenged to explore their own racial identities. The fact that individuals within our organisations tend to challenge the very existence of racism is in itself a microaggression.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews