Reading motivation matters. Far too many young people in our schools can read, but do not choose to do so. They are not motivated to make the time for it in their lives. Perhaps they have had negative reading experiences in the past? Perhaps they were never read to at home? Perhaps they struggled with reading (and still do)? Or perhaps they have simply not yet found what reading is good for – what’s in it for them.

These young people need well informed and reflective Reading Teachers who are determined to inspire and engage every single pupil as a reader. Such educators, who are readers in their personal lives and teachers of reading in their professional lives, constantly reflect on reading and being a reader in order to enrich their provision and more effectively nurture recreational reading (Cremin et al., 2022).

However, even for Reading Teachers, motivating disengaged readers is not easy. Some of these young people will have been demonstrating their disinterest for years, separating themselves from the keen readers – those they may perceive as ‘boffins’ – and adopting an indifferent or negative attitude to reading. Many actively claim and sustain the identity of a disengaged reader. In reading time, these students may be unable to settle, may pretend to read or merely flick through the pages of a text. During reading aloud, they may look as if they are listening, but simply be taking a short break, thinking about their own concerns. Consequently, they will be unable to participate in any related conversations; they are likely to remain on the edge of the classroom reading community.

Concerns about reading enjoyment

Worryingly, recent National Literacy Trust research, drawing on data from 70,403 young people suggests that reading enjoyment is at its lowest level since 2005 (Cole et al., 2022). It declines with age and less than half of the 8 to 18 year olds surveyed reported enjoying it (47.8%). More disturbingly still, the pre-existing gaps between boys and girls and between those on free school meals (FSM) and others, appear to have been aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic (Cole et al., 2022). Boys who received FSM in 2022 were the most likely to report that they never or rarely read; only 1 in 5 reported reading daily, a figure probably amplified by the social desirability bias common to all surveys. Placed alongside international concerns around young people’s attitudes to and engagement in recreational reading (OECD, 2021), these data indicate professional action is urgently needed.

What do we need to know?

To motivate disengaged readers, teachers need very considerable knowledge and understanding. Knowledge of research into reader motivation, knowledge of diverse texts that might tempt the young, and knowledge of each unique young reader. They also need pedagogic knowledge, not a random list of eclectic activities to try, but knowledge of rigorous and research-informed approaches that they can flexibly deploy to encourage their pupils to read recreationally for their own pleasure and information.

Drawing on Bernstein (2000), I suggest that educators need both ‘knowledge reservoirs’, (generated by experience and understanding of theory and research), and ‘knowledge repertoires’ (strategic approaches to utilise in action). Understanding research and reflecting on evidence, enables Reading Teachers to develop principled practice and, through careful monitoring of this, evaluate its impact on young people’s desire to read.

This article, which explores reading motivation and self-determination theory, also considers classroom consequences linked to supporting all readers, but particularly those who Moss (2000) coined as ‘can but don’t read’ pupils – the disengaged. But first let’s turn to our goals for these readers.

What are our intentions?

Do we want these less engaged readers, whose behaviour is sometimes challenging, to participate more positively in school reading activities? Do we want them to contribute more creatively and critically during English teaching? Do we want them to struggle less, to develop their fluency and comprehension? Do we want them to find reading sufficiently absorbing so they choose to read more frequently at home, and, potentially at least, become lifelong readers?

All these interrelated aspirations would be advantageous, but the last is particularly potent. Choosing to read – that is reading for pleasure, regularly and widely and in one’s own time – is positively associated with richer general knowledge and vocabulary, improved spelling, higher reading comprehension and wider school achievement (Torppa et al., 2019). Those young people who report reading regularly outside school also score highly on psychological wellbeing scales (Impact Ed, 2022); additionally, daily reading is linked to better behavioural adjustment at the start of adolescence (Mak and Fancourt, 2019).

Furthermore, OECD data consistently show that ‘engagement in reading is strongly correlated with reading performance and is a mediator of gender or socio-economic status’ (OECD, 2021). So, finding effective ways to motivate and support all pupils to develop the habit of reading is a matter of social justice. It can help address societal inequities and, as the International Reading Association states, is every young person’s right (ILA, 2018). So how might theories of reading motivation help?

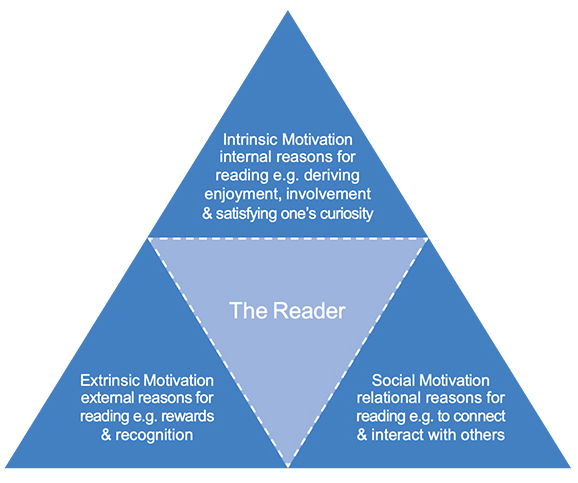

Figure 1: The multi-dimensional nature of reading motivation.

Figure 1: The multi-dimensional nature of reading motivation.

Reading motivation: a multidimensional construct

The relationship between reading motivation, reading engagement, and achievement has been studied for decades, with research indicating a clear correlation between these three strands, often linked to the amount of reading undertaken (e.g., Wigfield and Guthrie, 1997; Hebbecker et al, 2019). Many psychological researchers, viewing reading as an individual endeavor, highlight extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Others, looking through a broader social-cultural lens, view reading as a social practice, and thus draw attention to the context and the motivating influence of friends, peers, parents and teachers (e.g., Cremin et al, 2014; McGeown et al, 2020).

These perspectives on young people’s reasons for reading highlight, for example, that external reasons for reading are often linked to a reader’s desire for rewards and recognition. Internal reasons for reading can be linked to a reader’s desire for involvement in a narrative, a personal passion or interest, and social reasons for reading can be linked to a reader’s desire for interaction and relationships with others. Understanding that reading motivation is multidimensional – influenced by extrinsic, intrinsic and social factors – can help practitioners nurture volitional reading more effectively.

The available evidence indicates that reading for pleasure is far more closely associated with intrinsic than extrinsic motivation (e.g., Hebbecker et al, 2019; Orkin et al, 2018). If young people are only reading for prizes or rewards, then, as this research shows, they are unlikely to persist when the incentives are removed. Additionally, excessive extrinsic motivation can have a detrimental effect on children’s reading comprehension (Schaffner et al., 2013). Whilst this is a complex issue and readers may be intrinsically and extrinsically motivated at the same time, it is very tempting in school to offer rewards as enticements to young, disinterested readers.

The allure of extrinsic motivation

Extrinsic motivation, with the best of intentions, can come to dominate institutional practice. Reading in school is easily made into a competition. Reading thermometers, personal paper bookshelves, reading road tracks and rockets to the moon publicly demonstrate the apparent ‘prowess’ of individual readers or a class’s ‘progress’ in comparison with others.

Yet such competitions and plaudits pay limited attention to the nature or demand of the books that the pupils have read, or to the expertise or commitment of individual readers. Moreover, stickers, stars, certificates, bookmarks and prizes for being the ‘reader of the week’ or a ‘word millionaire’, can constrain children’s conceptions of reading. As one teacher told me, ‘My class equate reading with a competitive test score’, due, she felt, to the online reading system they used.

Whilst much depends on context and the way rewards are given, competitions between classes or between readers across the school can inadvertently serve to demoralise reluctant or weaker readers. Research suggests they either remain detached from such initiatives, or feel they are letting their class down by not reading more books, more quickly (Cremin et al., 2019; Orkin et al., 2018) – as if speed or the number of books read were the intended goal.

In one school, where I was studying disengaged boy readers, a bar graph in the staffroom displayed the number of parents in each class who had signed their child’s home-school reading record at least four times that week (Hempel Jorgensen et al., 2018). Every Friday in assembly, the ‘winning’ class was announced, praised, and given a certificate, popcorn and a choice of film to watch that afternoon. During the previous month, the Year 6 class had won every week. On visiting, the children openly told me that they signed their own reading records: ‘We’re free readers, so why shouldn’t we?’ Why not indeed?

Such examples highlight the need to consider the consequences of our attempts to increase reader engagement. Maybe too we could offer more appropriately proximal rewards, related to the activity we are trying to nurture, such as book tokens, books, credits towards an author visit and so on. Although these rewards will tend only to encourage those pupils who are already self-motivated readers.

Self-determination theory applied to reading

To examine reader motivation, self-determination theory is often used (Ryan and Deci, 2000). This suggests that to motivate ourselves and for wellbeing and growth – that is for optimal human functioning – we are driven by three core psychological needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. Applying this to reading, we can see that to be motivated as readers pupils need a high degree of agency, volition and choice (autonomy), a sense of self-efficacy and a positive reader identity (competence), and that they need to feel part of a network of readers with whom they can connect (relatedness).

This trio of needs are interrelated, such that feelings of competence will not enhance intrinsic motivation unless accompanied by a sense of autonomy. Reading studies show that when these three basic needs are fostered, this not only impacts on pupils’ attitudes to reading, but on the frequency of their reading engagement behaviours, and that it positively influences their language comprehension (Orkin et al., 2018). Let’s explore each in turn.

We cannot require young people to read in their leisure time nor insist they enjoy it. We can and should, however, invite, inspire, model and engage the young in reading for their own purposes.

Autonomy

Reading for pleasure is mandated in England (DfE, 2013) and included in all UK curricula, yet we cannot require young people to read in their leisure time nor insist they enjoy it. We can and should, however, invite, inspire, model and engage the young in reading for their own purposes, supporting their development as volitional readers who can and do exercise their agency, discrimination and choice.

To facilitate the autonomy of young readers requires knowledge of diverse, contemporary, and culturally relevant texts, and knowledge of the pupils as readers – their interests, attitudes, preferences, practices and skills (Cremin et al., 2014; Ng, 2018). With a rich repertoire of diverse texts and an understanding of individual students, teachers can make tailored text recommendations aligned to their interests and skill level, whilst still offering choice and fostering agency. At all costs we need to avoid imposing adult selections upon readers; their right to choose what to read independently must remain sacrosanct.

Gathering formative information about young people as readers enables Reading Teachers to help the young make wise, successful choices that are more likely to satisfy their goals. A range of tools, such as surveys, reading rivers, reader identity drawings, reading detectives and 24-hour reads, can fruitfully lead to informal conversations and conferences that deepen practitioners’ knowledge about each unique reader. This can prevent assumptions being made about what text types pupils of different genders might like; for example, a recent study challenges the discourse around boys preferring non-fiction (Scholes et al, 2020). Wider understanding of the life interests of less motivated readers may also prompt a review of the texts available and lead to the provision of an increased variety of genres that appeal to more pupils (McGeown et al., 2020).

As research indicates that choice and reader interest significantly enhance readers’ intrinsic motivation and engagement, support for browsing and text selection is also invaluable. Young people overwhelmingly report relying on ‘what’s on the shelf’ to select their next book (Cremin and Cole, 2022), so curating and regularly changing themed displays, impassioned text recommendations, reading aloud and ‘book blessings’, as well as opportunities to participate in peer-to-peer recommendations are needed. Otherwise, pupils may become overwhelmed by the choice available and fail to find a text that is personally relevant, speaks to their interests or inspires.

Self-efficacy

We all need to feel effective, as professionals in school and in our home lives. As educators we appreciate the significance of learners having a high degree of assurance and self-efficacy and want all young people to develop a positive attitude to reading, positive reader identities and a strong sense of self-worth. Reading Teachers work to ensure disengaged readers recognise that they can read and make discerning choices, that they have the confidence to voice their views and that their opinions are valued and accepted. These educators often explore the rights of readers – to give up on books, to skip passages, and to read at their own pace and in their own way.

Young people’s perceptions of reading and of their own competence as readers can both power them forwards and hold them back. Deeply disengaged readers in particular need to experience success and receive positive affirmation from their peers and teachers, but such success should not be confined to reading scores or ages. Reading and being a reader encompasses far more than decoding and comprehension, so it is crucial that as adults we get to know individual readers, build personal connections, and give these less motivated pupils our full attention. This will help us notice even the smallest dispositional identity shifts or moments of ‘almost interest and engagement’ and enable us to try and build on these.

However considerable sensitivity is needed: any sense of targeting these ‘reluctant’ readers, who are likely to have low self-esteem, risks making them feel singled out and may further undermine their assurance. Additional provision may well be needed, but such provision will need to be invitational, varied, responsive and predominantly owned and shaped by the readers themselves. It will probably also need to be subtly sustained over time. It is a demanding marathon not a quick sprint for these young people to reposition themselves as potentially interested in reading, especially when they may have spent years determinedly rejecting any notion of themselves as readers in school.

Relatedness

As adults we recognise our need for belonging – we are social animals. Likewise, many if not all of us, find reading satisfying in part because it enables us to interact with and connect to others – our partners, friends, family and work colleagues with whom we discuss and debate much of what we encounter. Reading is both a social and relational experience, but those who are less engaged may never have experienced it as such. Nonetheless, these pupils’ peers, librarians, learning support assistants, parents and teachers can be reading role models who inspire and encourage, explicitly and implicitly. By sharing their pleasures in reading, offering connections, recommendations and opportunities to debate meanings in relaxed non-assessed contexts, adults and peers can influence the attitudes of our least engaged readers (Cremin et al., 2014; Merga, 2017).

‘Works of art’, Oatley argues, ‘are surrounded by orbits of discussion’, and he goes on to argue that ‘to talk about fiction is almost as important as reading it in the first place’ (2011, p.178). Chatting about a ‘book in common’ with trusted others (perhaps one that has been read aloud to the class, or that a few friends have also read), not only deepens pupils’ understanding, but can nurture connections. So multiple copies of texts, book clubs and ‘reading spines’ (the non-required kind) that trigger book blether between readers have the potential to stimulate the social motivation to read.

Additionally, social reading spaces in and around the school, that inspire and invite young people to share the experience of reading are worth developing and monitoring. Relaxed reading times in libraries, outdoor areas, corridors and classrooms often include spontaneous reader to reader conversations and book exchanges, triggering social bonds around reading and a sense of belonging and relatedness. Reading Teachers’ own mini-libraries that encourage dialogue and reciprocal recommendations between them and their pupils, can also lead to stronger relational connections that encourage and support less engaged readers.

In sum

Motivated readers find the experience so engaging that they participate in it frequently at home for their own purposes and share their pleasure with others. These young people have an in-built advantage. By contrast, those who remain disengaged as readers are disadvantaged – academically, personally, and socially. Fostering an intrinsic and social desire to read in young people takes time and talent, knowledge and expertise. It is particularly challenging when pupils who have spent years positioning themselves as ‘non-readers’ in school, have developed an entrenched view that reading is not for them.

Reading Teachers work to make the experience of reading for pleasure less schooled and system-oriented, and far more authentic, real and personally and socially relevant.Such students benefit from being supported by Reading Teachers, who recognise the importance of autonomy, self-efficacy and relatedness, and who, through constantly reflecting upon their own practices and rights as readers, come to re-view reading and the significance of readers’ identities. These teachers shape their practice in responsive ways. They work to make the experience of reading for pleasure rather less schooled and system oriented, and far more authentic, real and personally and socially relevant to each young reader.

Permission given by National Association of Teachers of English who first published this article

For strategies and support on reading for pleasure, see Https://ourfp.org/.

Do consider leading or joining a local OU/UKLA Teaching Reading Group – CPD for RfP to support you and others on your journey as a Reading Teacher

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews