In England, where reading for pleasure is mandated (DfE, 2013), the term is often used interchangeably with ‘reading for enjoyment’ or developing a ‘love of reading’. Such reading can involve any kind of text: novels, magazines, poetry, comics or non-fiction for example, in electronic as well as in printed form.

It

can take place anywhere: at home, at school,

in a café, on a bus (or any form of

transport), on a beach, in a park (or any leisure location) – literally anywhere. At the core of reading for

pleasure is the reader’s volition, their agency and desire to read, their

anticipation of the satisfaction gained through the experience and/or

afterwards in interaction with others. Historically, reading has often been characterised as a personal solitary

experience conducted in privacy, yet more recent research has

revealed the profoundly social nature of reading, of being a young reader and

of reading for pleasure.

Different terms are used internationally to capture the dispositions and motivations of those children and young people who choose to read and do so regularly. Such reading is often described as ‘free voluntary reading’, or ‘independent reading’, in order to capture the reader’s sense of agency and choice (Krashen, 2004). It has also been described as ‘recreational reading’ (Ross, McKechnie and Rothbauer, 2006; Schugar and Dreyer, 2015), reading undertaken for the personal satisfaction of the reader, in their own free time.

Synonyms for pleasure include desire, preference, wish, choice and liking – all of which speak to the reading for pleasure agenda and young people’s agency as readers.

Exploring the notion of ‘pleasure’

Reading for pleasure as a concept within education is potentially problematic; it is open to multiple interpretations and can create confusion for educators who work to make all the reading undertaken – in English lessons, in projects and in cross curricula and extra curricula contexts – pleasurable. But in order to foster reading for pleasure in schools, homes and community contexts, conceptual clarity is essential, alongside awareness of the subtle differences between reading for pleasure, pleasure in reading and their synergies. Children and young people’s perceptions of reading for pleasure also deserve attention.

Reading for pleasure is increasingly recognised as a ‘purposeful volitional act with a large measure of choice and free will’ (Powell, 2014). Whereas pleasure in reading refers to pleasure in the experience, regardless of whether the reader was able to exercise agency in the context. For instance, listening to a bedtime story read by a parent may well be a highly enjoyable and valuable experience, although it will not necessarily lead to the child choosing to read in their own time, that is reading for pleasure. Likewise, finding pleasure in school-led extrinsically set reading tasks may or may not lead to children choosing to read in their own time.

Conceptual clarity over reading for pleasure, is essential for fostering it in schools, homes and communities.

As discussed more fully in a later section of the review, intrinsic reading motivation (reading for its own sake), is more positively associated with reading for pleasure, with reading frequency and enhanced reading outcomes than extrinsic reading motivation (e.g. Scheifele et al., 2012; Troyer et al., 2019). The latter refers to reading for recognition, for reward or to please teachers/parents. Research also indicates that the relationship between intrinsic motivation and reading skills develops at the early age of 6 years (McGeown et al., 2015) and that children can be both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated at the same time (McGeown et al., 2012).

The positive connotation of the word ‘pleasure’ also deserves nuancing when examining young people’s volitional engagement in reading. The experience itself may evoke a wide range of feelings and responses, including for example, sadness, irritation, anger, and discomfort as well as joy. Nonetheless if the reader sustains their engagement, they are likely to be reading for some form of satisfaction, in response to their own goals. While it has been suggested that reading for pleasure can be defined as ‘Non-goal-oriented transactions with texts as a way to spend time and for entertainment’ (BOP consulting, 2015), children do choose to read for diverse personal purposes and goals, consciously and unconsciously. Their own goals and motivations shape their reading choices and may lead them to read different text types (McGeown et al., 2015, 2020). For example, they may read in order to satisfy their curiosity and understand more about dinosaurs, space, their football team, or women in history, or may read in order to relax, or may seek the enjoyment of revisiting familiar characters in a book or comic series. Many will also value the opportunity to connect to and experience others’ lives (fictional and real), and in the process find emotional succour in reflecting upon their own. As Sanacore observes, when individuals read for pleasure frequently, they ‘experience the value of reading for efferent and aesthetic processes, thus, they are more likely to read with a sense of purpose’ (2002:68).

Some studies focus on the nature of the pleasure experienced by those young people who choose to read in their own free time. Several of these studies draw on data from the OECD Programme of International Student Assessment (PISA), which regularly assesses the reading attitudes and attainment of 15 year olds. In one such study, Cheung (2016) claims that fondness for reading (defined in his work as readers who follow their hearts), aspiration for reading, and being good at reading are seen as salient elements of readers’ engagement which affect their reading performance.

In a study of the reasons for reading offered by 9–10-year-old readers (n:33), the dominant drivers the children reported linked to their affective engagement in texts; the feelings and emotions triggered by reading and the opportunity to become immersed in texts (McGeown et al., 2020). Another study of avid adolescent readers’ perceptions of free reading (n:29), suggests that such choice-led reading, including the reading of genres typically marginalised in school (e.g., romance, fantasy, vampire, dystopia and horror) offers teenagers five distinct kinds of pleasure (Wilhelm, 2016). These include:

- The immersive pleasure of play: e.g., getting lost in a book and living through the text.

- Intellectual pleasure: e.g., finding out about issues of interest in the world and solving problems in narratives.

- Social pleasure: e.g., belonging to a community of readers and connecting to others through reading as well as identifying as a reader.

- The pleasure of functional work: e.g., using reading to learn, think, and act in different ways, and using reading to shape one’s writing.

- The pleasure of inner work: e.g., using reading to learn about oneself, to imagine oneself in different situations and consider options.

However, this study of the young people’s perceptions, indicates that only their intellectual pleasure was directly fostered in school. Wilhelm (2016) urges educators to recognize the central role of pleasure and its linked compatriot – choice – in developing lifelong readers. It is surely a professional responsibility to nurture readers who engage deeply, creatively and critically with the meanings and possibilities offered.

Reading engagement and reading for meaning

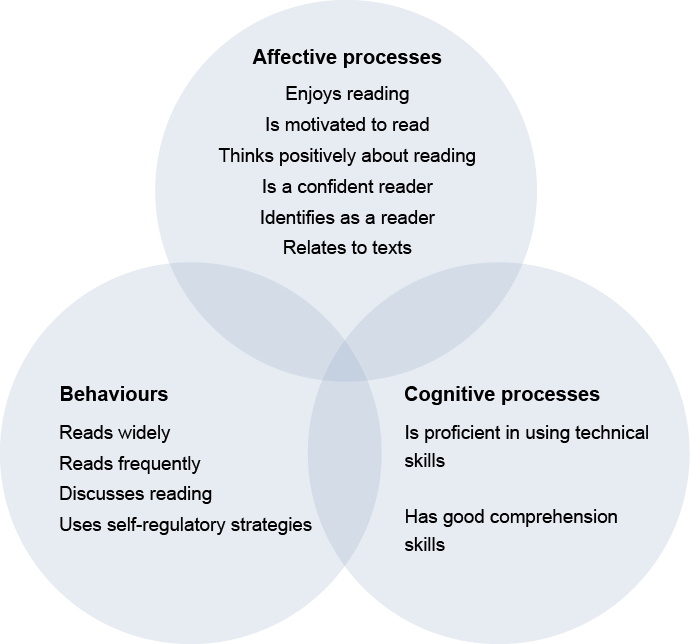

Reading engagement, a multidimensional construct studied in settings such as home, school, and the workplace is frequently associated with the concept of reading for pleasure. Engaged readers are those who want to read, who regularly make time for reading, and who find satisfaction through the process of thinking about the text’s meaning. Such readers tend to be motivated, display positive attitudes to reading, are sufficiently assured to make in-depth meanings and are likely to want to discuss texts with others. This summary aligns well with the OECD’s (2016) broadened conception of reading which acknowledges that there are motivational and behavioural characteristics of reading, as well as cognitive ones. Their re-conceptualisation of reading, first used in the 2019 PISA survey, complements the OECD’s current definition of reader engagement.

A person who is literate in reading not only has the skills and knowledge to read well, but also values and uses reading for a variety of purposes. It is therefore a goal of education to cultivate not only proficiency, but also engagement with reading.

Engagement in this context implies the motivation to read and comprises a cluster of affective and behavioural characteristics that include an interest in and enjoyment of reading, a sense of control over what one reads, involvement in the social dimension of reading and diverse and frequent reading practices. (OECD, 2019, p.29)

A depiction of this developed by the National Literacy Trust (see Figure 1) summarises some of the key affective processes and reading behaviours of readers who not only can, but who do choose to read and read regularly.

Figure 1: Top-level tripartite conceptualisation of what we mean by “reading” (Clark and Teravainen, 2017, p2)Three circles overlapping. Top circle says: Affective processes - Enjoys reading, Is motivated to read, Thinks positively about reading, Is a confident reader, Identifies as a reader, Relates to texts. Bottom left says: Behaviours - Reads widely, Reads frequently, Discusses reading, Uses self-regulatory strategies. Bottom right says: Cognitive processes - Is proficient in using technical skills, Has good comprehension

Figure 1: Top-level tripartite conceptualisation of what we mean by “reading” (Clark and Teravainen, 2017, p2)Three circles overlapping. Top circle says: Affective processes - Enjoys reading, Is motivated to read, Thinks positively about reading, Is a confident reader, Identifies as a reader, Relates to texts. Bottom left says: Behaviours - Reads widely, Reads frequently, Discusses reading, Uses self-regulatory strategies. Bottom right says: Cognitive processes - Is proficient in using technical skills, Has good comprehension

Through the motivated process of finding, making and thinking about meaning, engaged readers develop their understanding and capacity to reflect upon and evaluate what they read, and at the same time they nurture their desire to read. Engaged readers are not only motivated to make connections, which might be intra-personal (within person), inter-personal (between people), or inter-textual (between texts) (Smith, 2005), but are often socially interactive and keen to discuss their views and understandings with others – friends, family, teachers and peers. This deep engagement in the processes of making, sharing and developing meaning through reading and discussion, is intrinsically motivating, and affords many benefits to young people who choose to read for pleasure regularly in their own time. It is to the myriad benefits associated with reading for pleasure which this review now turns.

To reference this article: Cremin,

T. Hendry, H. Chamberlain,

L and Twiner, A. (2022)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews