As a PhD design student at The Open University, I have been exploring ways to teach anti-racist forms of fashion design. In my research many lessons can be learned from the seminal 1971 book Design for the Real World by designer and educator Victor Papanek, which argues that designers must think about their moral responsibilities and the ‘real world’ to design in more equitable ways. Exactly fifty years later, such issues are as urgent as ever in the context of climate change, increasing social inequalities and racial injustice as highlighted by the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet recent calls to decolonise design highlight how design continues to be shaped by patriarchal, Eurocentric and neoliberal thinking, especially through design education.

In October 2020 I was invited by The Open University to give a presentation on my PhD research, as part of ‘Black History Month’.

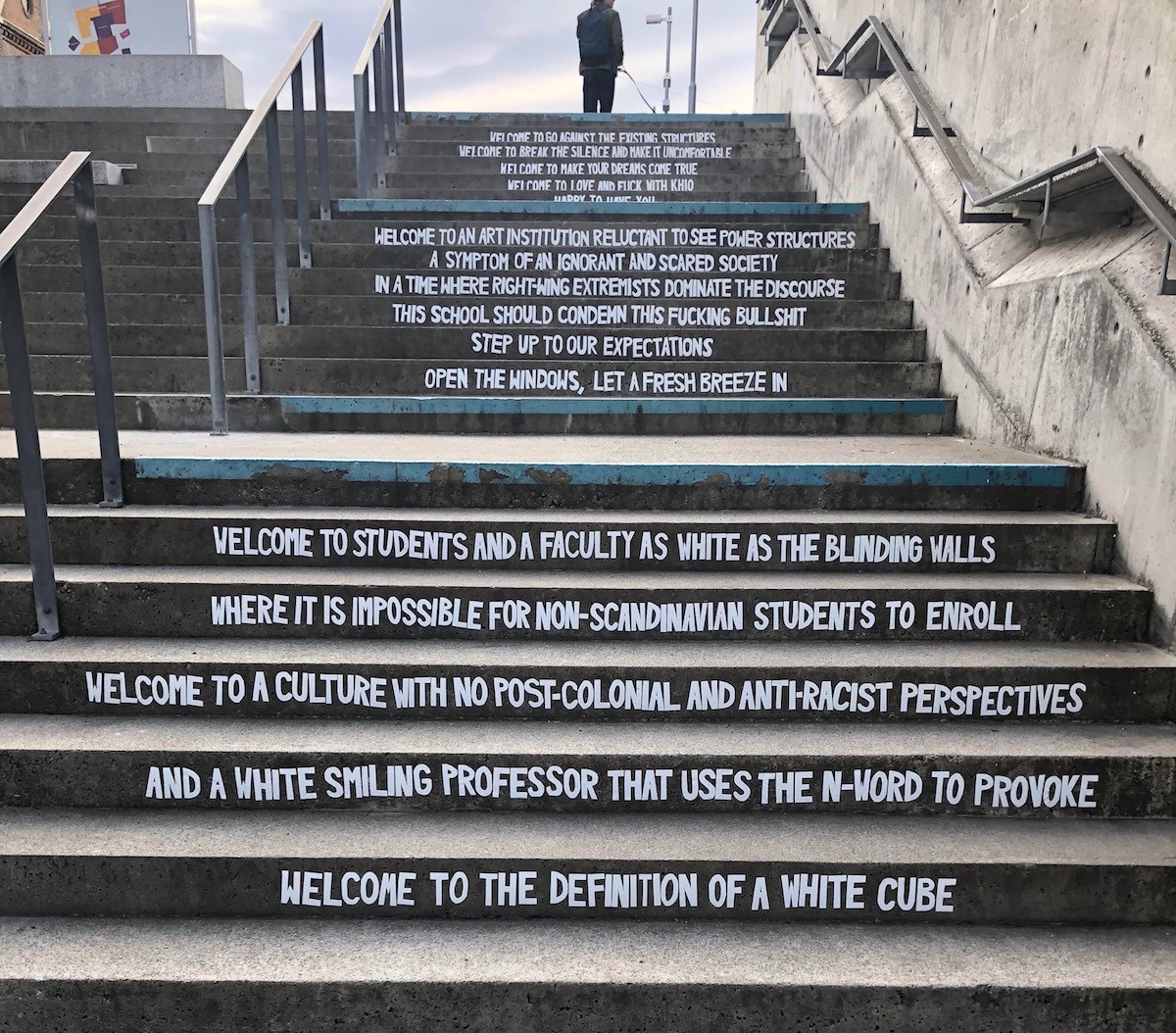

I began by discussing student-led campaigns to decolonise art and design in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in the UK and beyond. These campaigns have drawn attention to racist design practices such as the use of stereotypical images of Black bodies, cultural appropriation, the devaluing of non-western art and design and the underrepresentation and exclusion of people of colour – especially women – in art and design HEIs. These include: Royal College of Art, University of the Arts London, and Glasgow School of Art.

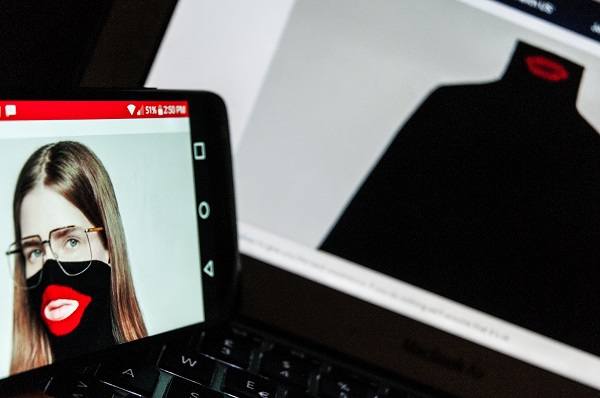

Stereotypical images of black bodies: 'Blackface' jumper by fashion label Gucci, 2019

Stereotypical images of black bodies: 'Blackface' jumper by fashion label Gucci, 2019

In many design HEIs staff remain predominantly white, and most women of colour – and especially Black women – are underrepresented (see Gabriel and Tate, 2017).

... I was taught a dominant Eurocentric fashion design education, and worse, began to teach the sameThis is also true of how I experienced design education in the UK, where I was taught a dominant Eurocentric fashion design education by mainly white educators, and worse, began to teach the same: for example, using fashion history books which mainly focus on European male fashion designers; using resources from the Victoria and Albert Museum which show cutting edge fashion as the domain of Europe and exclude most fashions from beyond Europe, for example no displays of African fashions; and, teaching pattern cutting with mannequins and pattern cutting blocks which reproduce heteronormative body size and ableist norms. My PhD research now aims to challenge such dominant Eurocentric thinking and create spaces for inclusive and democratic forms of fashion design education that re-think fashion with a more plural narrative, rather than with a singular, dominant European and Anglo-American/western/global north narrative. To do this I have been influenced by Black and women of colour feminist theories which have helped me better understand how hierarchical value systems continue to structure fashion cultures so that non-European fashion knowledges are excluded and erased from the classroom.

Black feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “the matrix of domination” in her classic book Black Feminist Thought to explain how systems of structural and historical oppression – class, race and gender, as well as disability, sexuality and others – work together to structure people's life chances. These different forms of oppressions do not operate independently, rather they are inter-related so that racism is not independent of capitalism, patriarchy is not independent of bias against people with disabilities, and so forth. Recently, design activist and theorist Sasha Constanza-Chock has argued that designers must recognise how the “matrix of domination” functions in the design process (Constanza-Chock, 2019). Constanza-Chock argues that designing things like garments or buildings or products, often reproduces existing societal structures resulting in access for certain types of people, such as white, male, heterosexuals, and exclusions – and worse, harm – for others, such as those who are black or brown, female and LGBTQ+.

To help me challenge how the “matrix of power” creates racist and sexist inequalities in fashion design education I have turned to Black and women of colour feminist writings that show the value of personal experiences. This has given me legitimacy to draw on my South Asian Indian heritage and value the fashions that my family has worn, such as my mother’s saris, valuing Indian clothing as a legitimate source of fashion knowledge, rather being used as a superficial motif or tokenistic symbol for design appropriation. I now teach students to think about their own biographies and value the clothing that their own mothers and grandmothers might have worn and question why these forms of everyday clothing are excluded from design education. I have also experimented with encouraging fashion students to design a garment for someone they love, rather than an imaginary size 8 female body. And I have explored ways to teach design beyond the boundaries of design disciplines through a women of colour feminist reading group that allows students of colour to collectively discuss ways to challenge the “matrix of power” in art and design education.

A group of fashion students use 'love' as a starting point to design for a grandparent

A group of fashion students use 'love' as a starting point to design for a grandparent

My hope is that re-imagining the design process through an understanding of the “matrix of power” might contribute to new forms of design practices that interweave different histories, economies and politics. In my PhD I have been testing whether this alternative design process might offer a space to counter the dominant hetero-normative, gendered, racialised, and ableist contexts prevalent in mainstream fashion cultures, and in doing so decolonise the practice of fashion design.

This alternative design process is not straightforward, sitting uncomfortably within conventional fashion design education departments, for students and tutors, for the disciplines of art and design and for HEIs too. This is because Black and women of colour feminist thinking in design education challenges the idea of the white male European designer as genius and problem solver. To address the crisis in design now requires students to lead the way, rather than the conventional top-down curricula from tutors. In this way a decolonised fashion design education has the potential to contribute to more socially responsible design practices which we can agree are now needed more urgently than ever.

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews