3 Social mobility

A key indicator of a meritocracy is the extent to which a society enables social mobility. Social mobility implies a more level playing field and fairer opportunities for individuals to change social or economic class or to achieve different status and outcomes than might otherwise be predicted for someone with their particular geographical, cultural or parental background. The education system could, for example, be used to this end. However, despite being a UK government priority, sustained and widespread social mobility remains elusive.

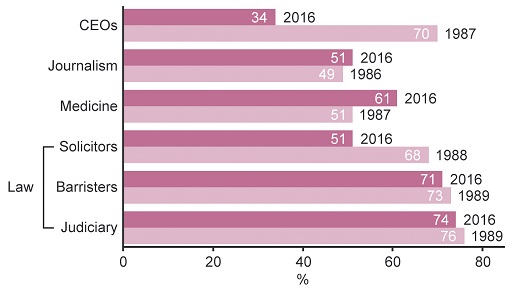

One way of measuring social mobility is to examine attained professional status in relation to an individual’s educational background. In the UK, it is important to bear in mind that private (also referred to as independent) schools tend to be used by families on high incomes to educate their children. High incomes are also commonly found in specific professions. Therefore a cycle of privilege occurs, with high income professionals sending their children to private schools and privately educated pupils going on to become high income professionals. This correlation between high income professionals and private school education can be observed statistically. The following graph is taken from the Social Mobility Commission report (Social Mobility Commission, 2017, p. 79) and shows the percentage of people at the top of a sample of professions who went to independent schools, at two points in time, the late 1980s and 2016.

The graph provides a mixed picture in terms of social mobility. CEOs of companies come from a wider range of educational backgrounds (one factor may be that the number of companies has increased since 1986). There has been, however, an increase in the proportions of privately educated individuals entering journalism and medicine and only minimal change in barristers and the judiciary. The next activity looks at a real world example involving a person from a non-private school background who defied the odds and became a barrister.

Activity 3 Adventures in social mobility

Hashi Mohamed came to the UK as a refugee aged 9. His identity as a poor Muslim Somalian could place him in a position of multiple disadvantages. During his childhood in the UK, he lived in crowded housing and didn’t achieve anything remarkable within school. However, Hashi now works as a barrister, considered to be an elite profession mainly occupied by people from privileged, privately educated backgrounds. Listen to Audio 1 in which Hashi discusses his change in situation.

Transcript: Audio 1 Adventures in social mobility

Discussion

Hashi offers an individualised explanation for his success that he describes as ‘social confidence’. One of the young people in the audio recognises and affirms that social confidence is a quality that many people she has met from private schools possess. Hashi explains how his social confidence emerged in part by reflecting on the possible life he might have lived and the opportunities presented to him as a refugee in a new country. Another of the young women talking with Hashi in the audio casts some doubt on his self-confidence message and argues that in fact adversity can cause some people to lose confidence.

Hashi also refers to ‘character’. This is a subjective concept that Hashi links to the skills and attitudes developed by people who face adversity. Although he doesn’t use the term, this would appear to have similarities with the concept of ‘resilience’ or ability to bounce back in the face of adversity. Far from being an inherent individual quality, ‘resilience’ is conventionally understood to emerge as the product of social relationships and experiences.

Finally, one of the young women identifies ‘adaptability’ as a quality that can help with social mobility. Hashi affirms that there is a requirement to be like a chameleon and adapt one’s behaviour to the context. This appears to have some similarities with ‘cultural capital’. ‘Cultural capital’ essentially involves possessing and applying a certain type of legitimate knowledge to a specific context. So, for example, to do well in the legal profession, it would be useful to have an awareness of the legal language, as well as the cultural and social topics, that many barristers share. Such legitimate knowledge may help build rapport and trust, which in turn may open up opportunities.