Find out about The Open University's Languages, cultures and communication courses.

In 2020, crime fiction overtook general and children’s fiction to become the best-selling literary genre in Britain (The Guardian, 2020). In 2021, two novels from Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series occupied first and fourth place in the UK’s best-seller list (Good e-Reader, 2022). In France in 2018, almost one in five of all books sold was in the crime fiction category (BePolar, 2019).

In 2020, crime fiction overtook general and children’s fiction to become the best-selling literary genre in Britain (The Guardian, 2020). In 2021, two novels from Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series occupied first and fourth place in the UK’s best-seller list (Good e-Reader, 2022). In France in 2018, almost one in five of all books sold was in the crime fiction category (BePolar, 2019).

For a literary form to achieve this degree of popularity, it must have a profound resonance with its readership, speaking to their subjective needs, their beliefs, wishes and fears. Moreover, literature not only reflects society but helps to shape how it sees itself, so the study of crime fiction constitutes an invaluable tool for understanding the development of the ideology and social imagination of a society in any given period.

European crime fiction since 1945

In 1945, most of Europe lay in ruins. The US government proposed a programme of economic reconstruction which, along with the prestige the US had gained from its role in the defeat of Nazism, led to an interest in the ‘American way of life’ in broad sections of the European public. In France, this influence was seen in the publication of the popular Série Noire crime fiction series. Initially, these were translations of American hard-boiled detective stories, but publishers soon realised that there was a market for original fiction in a similar style written by French authors.

Reconstruction was accompanied by a long economic boom in Western Europe, and the workforce in Europe’s growing economies benefited from higher incomes and more leisure time than previous generations. The new economic conditions led to changes in the world of crime fiction publishing, with a move from hardback lending libraries to the mass production and sale of cheap paperback editions.

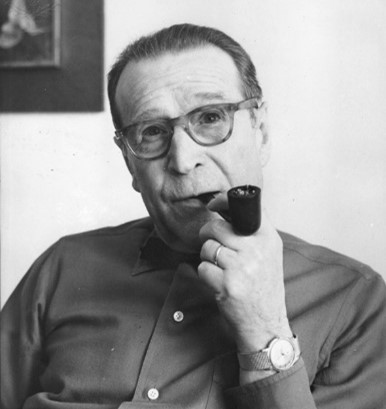

In the immediate post-war period and the early 1950s, crime fiction tended to be dominated by many of the same authors who had been popular in the 1930s. For example, Georges Simenon (pictured right) had written numerous Maigret novels before the war, and continued to write prolifically. In addition to huge domestic sales, the Maigret series was widely translated throughout Europe. Agatha Christie continued producing novels featuring her two iconic detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, and her nostalgic portrayal of an imagined lost past resonated both with a wide British middle-class readership and, simultaneously, in translation, with other European readers’ stereotypes of British life.

In the immediate post-war period and the early 1950s, crime fiction tended to be dominated by many of the same authors who had been popular in the 1930s. For example, Georges Simenon (pictured right) had written numerous Maigret novels before the war, and continued to write prolifically. In addition to huge domestic sales, the Maigret series was widely translated throughout Europe. Agatha Christie continued producing novels featuring her two iconic detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, and her nostalgic portrayal of an imagined lost past resonated both with a wide British middle-class readership and, simultaneously, in translation, with other European readers’ stereotypes of British life.

The increase in television ownership during the 1950s and 1960s provided a new medium for European crime fiction. Leading the way was Simenon’s Maigret, many of whose cases were adapted for the small screen in the UK, Italy and the Netherlands. In West Germany, the Jerry Cotton stories were mass produced in magazine format from 1954, leading to a popular TV series.

Crime fiction also began to turn in new directions. Boileau-Narcejac and Sebastien Japrisot in France devised complicated, suspense-filled plots which broke from the classic formats of cops, private eyes and upper-class amateur detectives. These elements would prove to have a major influence, crossing over into domestic cinema and even Hollywood.

Yet, despite the continuing economic prosperity, in the late 1960s, a wave of pan-European popular protest was developing. This student movement was accompanied by an increase in trade union militancy, notably in France, Italy and Britain. The pioneers in applying these new attitudes to crime fiction were the Swedish authors Maj Sjöwall (pictured left) and Per Wahlöö, whose series featuring the Stockholm detective Martin Beck began appearing in 1965. Over ten novels, Sjöwall and Wahlöö developed the idea that rather than condoning the status quo, detective stories could serve as a vehicle for social criticism.

Yet, despite the continuing economic prosperity, in the late 1960s, a wave of pan-European popular protest was developing. This student movement was accompanied by an increase in trade union militancy, notably in France, Italy and Britain. The pioneers in applying these new attitudes to crime fiction were the Swedish authors Maj Sjöwall (pictured left) and Per Wahlöö, whose series featuring the Stockholm detective Martin Beck began appearing in 1965. Over ten novels, Sjöwall and Wahlöö developed the idea that rather than condoning the status quo, detective stories could serve as a vehicle for social criticism.

In 1974, massive increases in the price of crude oil had an immediate impact on the economies of Europe, and with the onset of an economic recession, an increasing number of European writers began to question the capitalist order, producing stories which were highly critical of police corruption, links between business, politics and organised crime, and racism. Writers such as Fruttero and Lucentini (Italy), Didier Daeninckx (France) and Jakob Arjouni (Germany) opened a path that many others would follow.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, leading to the reunification of Germany and the collapse of the former Soviet bloc. Capitalism seemed to have triumphed, contrary to the expectations of many left-leaning writers. However, the social problems in European societies that these authors had highlighted remained unresolved.

The further economic and political integration of Europe, following the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 and the expansion of the European Union, led to greater cultural and literary exchanges. The phenomenon of so-called ‘Scandi noir’ was increasingly present, including in Britain with the success of TV crime dramas such as The Killing from Denmark and the Danish-Swedish co-production The Bridge.

There was also an assertion of regional identities in this time. The Rebus novels of Ian Rankin are Scottish, rather than generically ‘British’, Jean-Claude Izzo’s Fabio Montale trilogy is rooted in the specificities of Marseille, and Andrea Camilleri’s Montalbano series draws heavily on the culture of Sicily. (Andrea Camilleri pictured to the right.)

There was also an assertion of regional identities in this time. The Rebus novels of Ian Rankin are Scottish, rather than generically ‘British’, Jean-Claude Izzo’s Fabio Montale trilogy is rooted in the specificities of Marseille, and Andrea Camilleri’s Montalbano series draws heavily on the culture of Sicily. (Andrea Camilleri pictured to the right.)

The year 2008 saw a return to economic crisis following an international banking collapse. Governments across Europe implemented austerity measures, impacting further on a range of social issues. In addition to themes of professional crime, political, financial and police corruption, authors paid increasing attention to a wider range of topics. Racism, violence against women, homophobia, child abuse and environmental issues may have been addressed occasionally in earlier crime fiction, but these issues began to receive a more sustained treatment, reflecting their greater prominence in the minds of readers.

As the second decade of the twenty-first century ended, it would have been difficult to identify a single dominant trend in European crime fiction. Karim Miské’s Arab Jazz was an example of French crime fiction recognising the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country, while Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train placed the concerns of physical and mental violence against women at its centre. At the same time, the commercial success of Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series, released during the Covid-19 pandemic, seemed to indicate a yearning among many readers for the cosy crime fiction of an earlier age. The next twists in the ongoing plot of European crime fiction remain a mystery.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews