2.3 Evolutionary layers of the brain

A well-known model for understanding the basic structure of the human brain was developed by Paul MacLean in the 1960s (see Maclean, 1990). He called it the triune brain and suggested that three distinct brains emerged successively in the course of evolution and now coexist in the human skull. (It was mentioned earlier that evolution could not start building a structure from scratch – this is a good example!). We suggest that if you are not already familiar with the basic anatomy of brains then you spend a few moments exploring the brain using the interactive brain resource associated with this course [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] before you examine MacLean’s three brains model below. (Note that you need to sign in to the website to use this resource.)

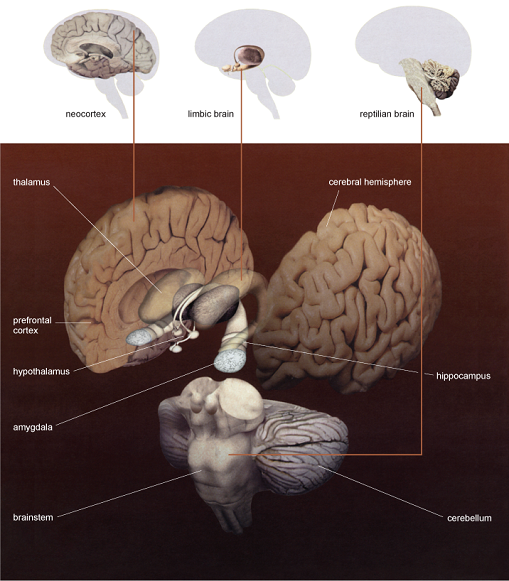

The ‘three brains model’ proposed by MacLean (Figure 4) were:

- The so-called reptilian brain, the oldest of the three in evolutionary terms, which controls the body’s vital functions such as heart rate, breathing, body temperature and balance. The main structures here are the brainstem and the cerebellum. One characterisation of the reptilian brain calls it ‘reliable but somewhat rigid and compulsive’.

- The limbic brain. This is also an evolutionarily ancient part of the brain and is found in mammals (such as rats, cats, dogs, monkeys, etc.). In the so called ‘limbic brain’ there is the amygdala, which registers unconscious memories of behaviours that produced pleasant or frightening experiences, and is closely linked to emotions, along with the thalamus, hypothalamus and hippocampus. The limbic brain has been characterised as ‘the seat of the value judgments that we make, often unconsciously, that exert such a strong influence on our behaviour’.

- The neocortex (the ‘new cortex’) evolved more recently in primates such as monkeys and apes, our closest relatives. It constitutes most of the cerebral cortex, which is highly developed in humans, with two large cerebral hemispheres. The neocortex, is thought to underlie language, abstract thought, imagination, consciousness and the development of culture and has been characterised as ‘flexible, with almost infinite learning abilities’.

Some neuroscientists find the ‘triune’ brain model simplistic and misleading. Certainly, it should not be taken literally. For instance, the ‘reptilian’ brain is not a distinct entity, identical to that of reptiles, within our own human brains. And our so-called ‘three brains’ do not operate independently of one another – we have one, highly interconnected brain, with different areas communicating with and influencing one another continually.

However, the triune brain concept is helpful in understanding that the influence is not always fully reciprocal – ‘older’ parts of the brain such as the limbic brain appear to have a stronger influence on the ‘newer’ parts than vice versa. For instance, neural pathways sending messages from the amygdala to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) which is part of the neocortex are extensive, but pathways sending messages in the opposite direction are relatively sparse.

As you will see if you look at the related OpenLearn course Understanding depression and anxiety, this has significance for the conscious control we can exert over our emotions.