Find out more about The Open University's Psychology courses and qualifications

What is neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity is the diversity of human minds and the fact that brains and neurocognition vary among all individuals. All these variations are ‘normal’ and ‘valuable’ with neurodiversity being the concept that neurological differences are to be recognised and respected as any other human variation. The term ‘neurodiversity’ was coined by the Australian sociologist Judy Singer in 1998, and stands in opposition of viewing people as ‘suffering’ from deficits, diseases or dysfunctions in their mental processing, suggesting instead that we speak about differences in cognitive functioning.

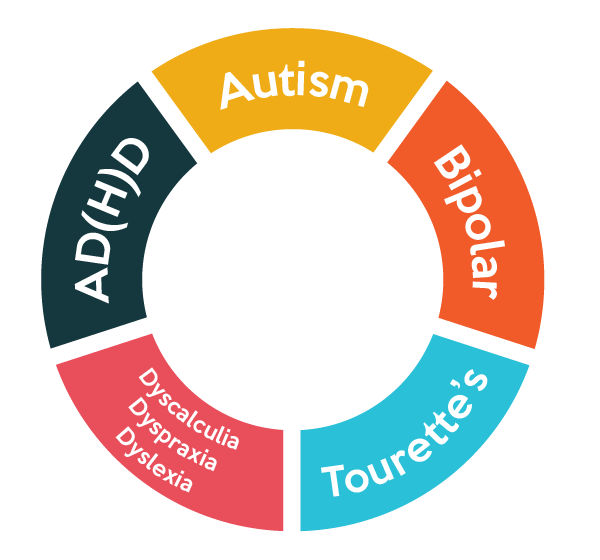

Proponents of the neurodiversity movement want to make it easier for all neurodiverse people to be able to contribute to society as they are rather than how society would want them to.The term ‘neurodiverse’ led to the neurodiversity movement, which was developed from the Autism rights movement; this initially meant only autistic people were viewed as neurodiverse. However, this has since expanded to include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyscalculia, dyslexia, dyspraxia, various mental health issues such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety issues, acquired memory losses, Tourette’s and other neurominorities.

Rooted in the social model of disability, neurodiversity sees disability as entrenched in society rather than the individual, and proponents of the neurodiversity movement want to make it easier for all neurodiverse people to be able to contribute to society as they are rather than how society would want them to. This means looking at the strengths of difference; someone who is dyslexic may have high levels of empathy and be more able to see the big picture when problem solving as well as struggle with reading. Having dyspraxia and having difficulties with coordination, movement, balance and organisation abilities may also provide a person with better soft skills such as active listening.

However, those who advocate the concept of neurodiversity do not disregard the struggles and difficulties that those people with ADHD, dyslexia, autism, bipolar disorder and other conditions will experience and need to overcome. Instead, while acknowledging these, they also recognise and celebrate the strengths and positive experiences these conditions can bring too.

Why do views of neurodiversity change depending on ethnicity?

Across the world, there are different views about how neurodiversity is understood and therefore defined. Some cultures are yet to accept the paradigm of neurodiversity and believe that experiences of ADHD, autism, etc are all forms of mental health disorders. Behaviours that are classed as different or a difficulty vary widely because of the different expectations of social behaviours and social norms.

One of the principles of neurodiversity is the idea of human competence being defined by the values of the cultures to which you belong.Diagnoses of neurodiverse conditions vary greatly in different countries. For example, in Oman, studies have shown that 1 in 1,000 people are on the autistic spectrum whereas in the UK, it is believed to be 1 in 90. Are we to believe that there are more autistic people in the UK or is there another explanation?

One of the principles of neurodiversity is the idea of human competence being defined by the values of the cultures to which you belong; dyslexia, for example, is based upon the social value that everyone should be able to read. One hundred and fifty years ago, this was not the case, and the ability to read had more to do with your socio-economic advantages than your neurological ability. Similarly, a diagnosis of autism requires presenting with issues within social interactions; this reflects the cultural value that suggests a preference toward relationships rather than an enjoyment of being alone.

Implications of racial differences in experiences of neurodiversity

The implication of the differences in value sets can be felt when diagnosing individuals. A lot of the diagnostic tools for assessing whether a person has a disability are based on Western norms. From a cultural approach, what is defined as ‘abnormal’ will depend on expectations and standards of the society and the cultures the individuals belong to. For example, in some Asian and African communities, giving eye contact to an adult or to someone in authority is considered to be rude and children are actively taught not to do this. Yet, not maintaining eye contact is widely considered to be an autistic trait and something most, if not all, professionals will be looking out for when offering a diagnosis of autism.

In the UK, it has been found that Asian school pupils (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and other Asian) are half as likely to be identified with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) as white British pupils. Linking this to the use of westernised diagnostics, it is possible to argue that cultural differences may explain this low incidence of Asian representation in the autistic community, as some of the features of these diagnostics are based on the norms for white British children and are not necessarily transferable to all children or young people.

If you are already being oppressed by society due to your ethnicity, it makes sense that you would avoid being identified as being neurodiverse.Also in the UK, black Caribbean and mixed white and black Caribbean pupils are twice as likely as white British pupils to be identified by their teachers as exhibiting Social, Emotional and Mental Health (SEMH) needs – a category within which ADHD falls. It has been suggested that this disproportionate representation is linked with the high likelihood of children and young people from Black And Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities living in stressful situations or to suffer from post-traumatic stress, meaning they are at greater risk of diagnosis/mis-diagnosis with ADHD. A research paper by Race On the Agenda (ROTA) in 2013 stated that ‘a disproportionate number of ethnic minority families live in highly stressful environments, thus making their children more vulnerable to hyperactivity’.

Yet it has also been argued that this over-identification could be linked to socio-economic disadvantages within these communities or, further still, this misrepresentation could be due to inherent biases and low expectations of teachers with regards to their black pupils, and a failure of schools to provide quality instruction or effective classroom management to non-white children.

Even when the parents, families and/or caregivers are aware that their child may have difficulties, fear of social stigma may deter them from seeking appropriate help and support. For instance, in South Korean culture, some consider autism to be a ‘genetic taint’, which diminishes the marriage prospects of other children in the family – this is similar to other cultures, which may view autism as a ‘curse’. Pre-existing stigmas within ‘othered’ communities play a part in avoidance of acknowledging difference – if you are already being oppressed by society due to your ethnicity, it makes sense that you would avoid being identified as being neurodiverse.

Final thoughts

The neurodiversity movement recognises that there is no one correct way of perceiving the world and the individuals within it. However, when there are dominant perspectives and beliefs placed on ethnicity globally, it is easy to see why this movement has yet to become universal. The dynamics around neurodiversity are similar to those which manifest for other forms of human diversity and these include the unequal distribution of social power. In attempting to find ways for neurodiverse people to live in harmony, we need to be mindful of racial and cultural differences and how these may affect identification of neurological difference.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews