2 A prince at the seaside

In this section we will take a closer look at the life of George IV and what brought him to Brighton.

The Prince of Wales (see Figure 2 ), known familiarly to his friends as ‘Prinny’, was born in 1762 and destined to become Prince Regent in 1811 following the onset of the madness of his father, George III. He finally became George IV in 1820, but reigned as such for only a decade, dying in 1830 at the age of 68. He is remembered as a great connoisseur and collector of art (setting a precedent for subsequent Princes of Wales to take an interest in architecture), most especially through his patronage of John Nash, who at his behest redesigned Buckingham Palace and created the elegant London developments still known as Regent Street and Regent's Park. Handsome, intelligent and accomplished, the prince was also highly emotional, duplicitous, painfully susceptible to flattery, wildly extravagant, greedy for excitement and personally theatrical. The Princess Lieven, wife of Tsar Alexander I's ambassador and a notable judge of character, described him as he was in the 1820s, as having ‘some wit, and great penetration’:

he quickly summed up persons and things; he was educated and had much tact, easy, animated and varied conversation, not at all pedantic. He adorned the subjects he touched, he knew how to listen, he was very polished … also affectionate, sympathetic, and galant. But he was full of vanity, and could be flattered at will. Weary of all the joys of life, having only taste, not one true sentiment, he was hardly susceptible to attachment, and never I believe sincerely inspired anybody with it.

(Temperley, 1930, p.119)

In early life the prince was also breathtakingly indiscreet, both in his youthful politics (he was a hard-core oppositional Whig rather than favouring the establishment party, the Tories, supported by his father) and in his youthful love affairs (which were many and various, culminating in the scandal of his private, unacknowledged, unconstitutional and therefore unlawful marriage to the Roman Catholic widow, Mrs Fitzherbert). As a result, and as so many heirs to the throne have done, during his twenties and thirties the prince enjoyed a strained relation with his father's court, which he found staid and stifling. His form of rebellion was to combine spendthrift dissoluteness (hence the anonymous print of 1787 depicting the prince as the Prodigal Son; see Figure 3 ) with the life of an aesthete, which found expression in the court he held at Carlton House. His set of associates included dandies such as Beau Brummell (who affected beautiful, consciously urban clothes and a pose of bored languor as he strolled up and down the Mall), sporting rakes like the Duke of Queensberry, and high-class courtesans such as Harriette Wilson. These were blended with society literati such as the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the millionaire connoisseur William Beckford (author of the torrid Oriental fiction Vathek: An Arabian Tale (1786), who purchased the famous statue of Napoleon pulled down from the Vendome Column, and the best-selling poet Thomas Moore, shot to fame by the success of his long Oriental romance poem Lalla Rookh (1817).

Carlton House, sumptuously decorated in the height of fashionable Francophile taste in line with the prince's Whig sympathies by the important architect Henry Holland (1745–1806), was the setting for a series of the extravagant parties which the prince so loved to give, culminating in the famous Carlton House fete in 1811 on his appointment as Regent. The dazzled Thomas Moore wrote to his mother about this fete, detailing the delights of the indoor fountain and the artificial brook that ran down the centre of the table, and concluding, ‘Nothing was ever half so magnificent. It was in reality all that they try to imitate in the gorgeous scenery of the theatre’ (quoted in Hibbert, 1973, p.371). Byron's friend and fellow radical poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, by contrast, was predictably outraged by the cost (see Hibbert, 1973, p.374). In the event Carlton House, with its rival court, did not prove far enough removed from his father to suit the young heir. Instead he would lure his raffish and brilliant society, with its love of extravagance and theatricality, out of the capital and down to the margins of the nation, to a place then called Brighthelmstone, some eight hours away by stage-coach (although in 1784 the prince achieved the journey in four and a half hours for a bet).

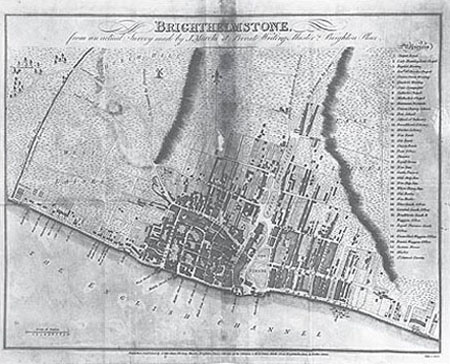

The Prince of Wales first visited Brighton (short for Brighthelmstone) in 1783, aged 21, staying with his uncle at Grove House on the Steine (or Steyne), a broad street that led from the seafront into the heart of town (see Figure 4 ). He was prompted partly by his ever-lively desire to escape the disapproving eyes of his father's court, and partly by the recommendation of his physicians, who suggested that sea water might ease the glandular swellings in his neck. This sea-water cure had been the original cause of the rise in the popularity of Brighton as a watering place, which had started around 1765, courtesy of a Dr Richard Russell of Lewes who had publicized the health-giving properties of bathing in, and drinking, sea water in his A Dissertation: Concerning the Use of Sea Water in Diseases of the Glands, etc . (1752). Sea water taken one way or another, according to Russell, would cure almost any disease, including ‘fluxions of redundant humours’, rheumatism, madness, consumption, impotence, rabies and childish ailments. Among the early visitors was Dr Johnson, but it was soon to become a resort for the fashionable as well. As one wag was to put it, high society ‘Rush'd coastward to be cur'd like tongues/By dipping into brine’ (unattributed, quoted in Roberts, 1939, p.3), or turned out to spy through telescopes on ‘mad Naiads in flannel smocks’ as they emerged briefly from their bathing machines (Pasquin, 1796, p.5).

Click below to view a larger version of the Map of Brighthelmstone.

These health treatments, generally undertaken after the rigours of the London season which ran from March until June, were much sweetened by the other pleasures that Brighton had on offer besides the beauties of nature. They included a racecourse, hunting, circulating libraries, promenading and ogling along the Parade, donkey-rides on the beach, balls and assemblies at the Old Ship and the Castle Inn, and the theatre, where you might have seen the celebrated actresses Mrs Siddons and Mrs Jordan. (The new Theatre Royal at Brighton was soon able to attract such London celebrity performers not just during the summer, when the London theatres were closed, but over the Christmas season too.) This landscape came complete with figures – rakes, parvenus, the frail lovelies of the so-called ‘Cyprian corps’ (a Regency euphemism for prostitutes, derived ultimately from the classical myth that Venus was born naked from the waves at Cyprus) and officers from the nearby military camp. The army came under the prince's personal command in his capacity as commander-in-chief, and many officers were his intimates; the arrival of the military therefore sealed the glamorous image of the resort. As Jane Austen was to write in Pride and Prejudice (1813):

In Lydia's imagination a visit to Brighton comprized every possibility of earthly happiness. She saw with the creative eye of fancy, the streets of that gay bathing-place covered with officers. She saw herself the object of attention to tens and scores of them at present unknown … she saw herself seated beneath a tent, tenderly flirting with at least six officers at once.

(Austen, 1967, p.232)

This invasion of London raffishness prompted the occasional fierce satire. Anthony Pasquin's poetic The New Brighton Guide (1796) describes Brighton in a note as

one of those numerous watering-places which beskirt this polluted island, and operate as apologies for idleness, sensuality, and nearly all the ramifications of social imposture … where the voluptuary [seeks] to wash the cobwebs from the interstices of his flaccid anatomy.

(Pasquin, 1796, p.5)

The painter Constable sourly described Brighton as ‘Piccadilly or worse by the sea’ and ‘the receptacle of the fashion and off-scouring of London’ (quoted in Leslie, 1951, p.123). But the prevailing view of Brighton was that, unlike more established resorts, it offered a picturesque, even a virtuously Rousseauesque, rustic informality, allowing visitors to escape the constrictions and excesses of life in town to partake of ‘pure air, rational amusement, and sea-bathing’ (Fisher, 1800, p.viii). As Mary Lloyd put it in her Brighton: A Poem,

it was a pleasing gay Retreat,

Beauty, and fashion's ever favourite seat:

Where splendour lays its cumbrous pomps aside,

Content in softer, simpler paths to glide.

This agreeable vision owed a good deal to the Prince of Wales himself, who both set the seal of fashionability upon Brighton (relegating its rivals, Bath and Tunbridge Wells, to middle-class dowdiness) and did much to exploit and reinforce this cult of Romantic love-in-a-cottage – to begin with, at least. Having rented a picturesque farmhouse on the Steine in 1784 for a couple of years, he determined in 1786 to reform, retrench and retire to Brighton, installing his new wife Mrs Fitzherbert just around the corner, there to live a life of simple, if self-dramatizing, poverty (see Figure 5 ). Strict economy notwithstanding, he commissioned his then favourite architect Henry Holland to convert the farmhouse into a gentleman's residence with good views of the sea and the Steine. Rebuilt in the early summer of 1787, it would come to be called the Marine Pavilion.

Exercise 3

Look carefully at the two prints which show the Marine Pavilion in 1787 and 1796 (Figure 6 and Plate 12 ), at the ground-floor plan of Holland's Marine Pavilion (Figure 7), and at the watercolour which shows the interior decorative scheme of the Saloon c.1789 (Plate 13). I should like you to make some notes along the following lines:

Describe some of the architectural features (both exterior and interior) that strike you.

Make a stab at identifying the architectural styles that this building evokes.

Consider the house's relation to its setting.

Consider what your observations might tell you about the young prince's vision of his life in Brighton.

Speculate on what the prince may have been intending to suggest by calling his newly modelled house a ‘pavilion’. (Here you might find it illuminating to consult the Oxford English Dictionary.

Click below to view the four images refered to in the exercise.

Discussion

Holland's Marine Pavilion is notably symmetrical in conception. The original farmhouse has vanished into the left-hand wing of the new structure, which is now mirrored by an identical right-hand wing with matching bays. The composition is centred on a domed rotunda fronted by slender Ionic columns. The building is whitish, unlike the surrounding brick buildings. The same symmetry is visible in Thomas Rowlandson's depiction of the interior of the Pavilion ( Plate 13 ). Mirror is balanced by mirror, seat by seat and fireplace by console. The plasterwork is uniform, and repeated in panel after panel and in the coffering of the ceiling.

The rotunda (and its columns) make clear reference to classical civilization. It is Roman in its evocation of the Pantheon and Greek in its Ionic columns. This Neoclassicism is further underlined by Holland's decision to clad the whole building in cream-glazed Hampshire tiles, mimicking the paleness of marble. The symmetry visible in the interior of the rotunda is similarly neoclassical. This scheme is also derived – via the interior designer Robert Adam (1728–92) – from the coffered interior of the Pantheon.

The Pavilion is orientated very strongly towards the main street on which it is located (the Steine) and therefore to taking part in the social display that was such a feature of this area. The house combines both modesty and grandeur: it is almost aggressively modest in height in relation to the other buildings around it, but at the same time it makes no effort to blend in with them.

The building suggests that the prince saw himself while sojourning in Brighton as passing incognito, disguised as a commoner. But at the same time it also suggests that the prince's disguise was meant to be penetrated; he might have been living in virtuous poverty, but this was poverty in the most sophisticated taste, poverty as fashion statement, poverty as a holiday from inborn and inalienable royal importance.

There is much to be deduced from a name. By calling his house a ‘pavilion’ – a term, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, which at this period (the 1780s) meant exclusively an Oriental tent, a temporary and moveable outdoor dwelling – the prince was invoking a striking series of connotations: of temporariness, of holiday and of fantasy escape. (In fact, the rotunda does have something of the appearance of a tent-like structure, and the architect Humphrey Repton (1752–1810) compared the interior effect to that of a marquee (see Dinkel, 1983, p.20).)

On the one hand, then, this building is thoroughly conventional. This sort of neoclassical architecture was an eighteenth-century Enlightenment shorthand for belonging to a well-heeled, cosmopolitan Whig landowner. The whole – dignified, sumptuous, but quite subdued in effect – is depicted by Thomas Rowlandson as populated with figures engaged in the polite and formalized conversation of good society (see Plate 13 ). On the other hand, the prince's retreat was founded in a fantasy of ‘dropping out’. The restless owner would not long remain content with this version of his Pavilion; but at its core through all its transformations lay a notion of self-dramatizing metamorphosis and of temporary, alternative and essentially irresponsible experience undertaken incognito. (An incident from the prince's early life is particularly telling here; in his twenties he fell for the beautiful actress Mary Robinson in the role of Perdita in Shakespeare's late romance The Winter's Tale. Perdita is apparently a shepherdess but is actually a lost princess; she meets and falls in love with Florizel, seemingly a shepherd but in fact a prince in disguise. Not for nothing were the couple promptly dubbed by London society and by the caricaturists ‘Florizel and Perdita’ – the prince clearly loved romantic slumming from very early on.)