3 From Enlightenment to Romantic?

In 1800, having divorced Mrs Fitzherbert and contracted a disastrous marriage with Princess Caroline of Brunswick, forced on him by the necessity of persuading the king to clear his vast debts, the Prince of Wales fled back to Brighton with his court. In 1801 he whiled away his time (and squandered Caroline's dowry) dreaming up extensions and changes to the interior decor of the Pavilion.

Of these, certainly the most interesting and prophetic was his development of the interior into a Chinese fantasy between 1802 and 1804, a development perhaps suggested by his fantasy of a ‘pavilion’ – a term that by now was being applied to small garden buildings of a Chinese style. He hung his newly decorated rooms with genuine Chinese wallpaper sent from that country's imperial court and crammed them with a collection of imported items supplied by the firm of Frederick Crace & Sons. These ranged in promiscuous profusion from model pagodas and carved ivory junks to birds’ nests, Chinese razors, silks and pieces of fine porcelain. Like Soane, he seems to have been taken with the idea of displaying a collection of curiosities, mounting the rare and the bizarre in witty and deliberately heterogeneous juxtaposition. Lady Bessborough wrote of the effect in 1805: ‘I did not think the strange Chinese shapes and columns could have looked so well. It is like Concetti in Poetry, in outre and false taste, but for the kind of thing as perfect as it can be’.

By ‘Concetti’ Lady Bessborough meant the elaborate ‘conceits’ (strained and conspicuously witty metaphors that yoke unlikely things together) of the sort characteristic of the lyrics of the seventeenth-century English poet John Donne.

It is important to understand, however, that the prince's liking for things Chinese was not especially innovative. The rage for Chinese imports had gone in and out of fashion throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as French and British traders had penetrated the huge Chinese empire. The rich and aristocratic, leaders of fashion, had typically amassed rare and beautiful objects from the Chinese export market, most especially porcelain and silks, which embodied superior technological skills that to date had baffled the West. So important did Europe become as a market for these wares that the Chinese invented a special export market, designing on vases and bowls painted scenes purportedly of European life but in a distinctively Chinese style. This English liking for Chinese products spilled over into a variant of Rococo style around the 1740s. Known as chinoiserie, this influenced the design of textiles, furniture and gardens in courts and great houses across Europe, including one belonging to the Russian empress, Catherine the Great (1729–96). The 1780s and 1790s saw in particular a fad for Chinese gardening in a ‘ grotesque ’ style. This resulted in the famous pagoda designed by Sir William Chambers (1726–92) for London's Kew Gardens, in Frederick the Great's Chinese-style tea-house at Sans-Souci in Germany, and in the similar Chinese tea-house in the grounds at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, all of which can still be seen if you care to visit them. Like the pleasures of the Gothick folly (exemplified in the building of Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire by the prince's vastly rich friend, William Beckford), this sort of ‘Chineseness’ bore witness to a rebellious undercurrent that ran counter to, and in parallel with, established Neoclassicism, although for the most part safely located outside the house in the grounds. As John Dinkel puts it:

Those essentially ornamental eye-stoppers, the innumerable sham Gothic ruins, pyramids, Turkish tents, pagodas, and Chinese teahouses that sprinkled gentlemen's estates, were all fashionable expressions of the impulse to break the established rules of classical taste.

(Dinkel, 1983, p.7)

Yet escaping into Chinese fantasy was, to the eighteenth-century mind, not an escape into the barbaric. The Chinese appeared to an Enlightenment eye to offer an alluring model of imperial stability, of gracious ritual and strict hierarchy, of wit, charming illusion, and the pleasures of narratives in miniature. The Chinese were supposed to be eminently civilized. This was one reason why Oliver Goldsmith's novel satirizing the follies of British society, The Citizen of the World (1762), took as its central figure a Chinese philosophic gentleman residing in London writing home in some bewilderment at the habits of the natives, and why Voltaire took the view that China was a sophisticated land of admirable stability peopled by philosophes. The connotations of China in the prince's day were, in short, those of luxury, gaiety and the trappings of rank (Dinkel, 1983, p.33), although increasingly towards the end of the eighteenth century this view was tempered by a sense that Chinese civilization was stagnant by comparison with the vigour of Enlightenment Europe.

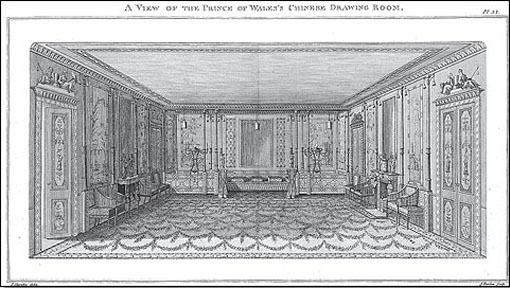

The prince himself was not new to the pleasures of connoisseurship in this area; by 1790 Carlton House already boasted the famous Yellow Drawing Room in the Chinese style (see Figure 8 ). At this time, Chinese taste was all the rage in ‘advanced’ circles. None the less, it was one thing to collect the occasional piece of beautiful china and the odd strip of hand-painted wallpaper, setting them in ‘exotic’ colour schemes, and quite another to collect pagodas, birds’ nests, razors and vast amounts of china. The one was an exercise in graceful allusion, the other a demonstration of a witty taste for the grotesque and the bizarre, increasingly characteristic of turn-of-the-century Romantic taste.

Click below to a larger version of A View of the Prince of Wales's Chinese Drawing Room.

Exercise 4

I'd like you to look carefully at Figure 8 and compare it with:

Rowlandson's sketch of the original interior of the Saloon in the Marine Pavilion (Plate 13) and;

the illustration of the Long Gallery, which shows a rather later decorating scheme designed by Frederick Crace around 1815 (Plate 5).

What, if anything, does the Yellow Drawing Room have in common with each of these schemes?

Click on 'View document' to see plate 13, interior decorative scheme of the Saloon.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 5, illustration of the Long Gallery.

Discussion

Clearly, all three designs do have in common an underlying concern with symmetry and balance, a thoroughly neoclassical and Enlightenment trait. But my own sense is that the Chineseness of the Yellow Drawing Room is more akin to the spirit of the sketch of the Saloon. It speaks of a cultivated taste, backed by plenty of money and leisure; it is decorative and witty, polite and, most important, formal, as befits a royal London residence. (The Saloon seems a little less formal in Rowlandson's conception – but then, it is part of a holiday house in a seaside resort.) By contrast, Crace's designs for the Long Gallery seem much more invested in alternative, exotic experience, perhaps straying outside the strictly polite. You may have noticed how the underlying neoclassical symmetries of the Long Gallery are broken, distorted and unsettled by the quite violent diagonals of the bamboo on the wallpaper, by the tiles that line the coving, mimicking a Chinese roof, and especially by the consciously ‘foreign’ lines of the cast-iron dragon columns that stand at each side of the passage. The colours are brilliant, and flamboyantly and unconventionally combined. The effect is akin to the idea of the picturesque: it privileges a roughness, a serpentine line, ‘variety’ and the power of a framed perspective. It is a theatrical experience – which perhaps is not so very surprising given that the Long Gallery (unlike the Saloon) was for looking down and walking through rather than sitting in.

What the differences between these interior schemes suggest to me is that by 1815 the prince's earlier ‘Enlightenment’ taste for chinoiserie had metamorphosed into something more ‘Romantic’, something less congruent with neoclassical order, balance and symmetry. That slight but definite tinge of the bizarre suggested by the collection of birds’ nests in 1802 would be much elaborated by the prince and his designers over the first two decades of the nineteenth century.

At the turn of the century, the governing idea of a ‘man of taste’ was changing. Whereas during the eighteenth century such a man would have been concerned to display his genealogy, his wealth and his classical education topped off with Grand Tour souvenirs in his house, he now invented himself by creating something strange and personal; hence the fantasy-world interiors of Beckford and Soane, ‘hungry for thrilling sensations evoked by ancient and Eastern artefacts’ (Dinkel, 1983, p.8). This intensely personal and sensational fantasy would become a hallmark of Regency, and Romantic, style. Dandyism in taste, and the ascendancy of the most famous dandy of them all, Beau Brummell, for several years the prince's boon-companion, was only just around the corner. The Pavilion's Chinese interiors, therefore, were to the prince an expression of Romantic subjectivity, a crystallization of his sense, shared by many contemporaries (including, for example, Soane), that he was a uniquely sensitive and involuted soul. As he was to write in 1808 to Isabella Pigot, Mrs Fitzherbert's companion:

I am a different Animal from any other in the whole Creation … my feelings, my dispositions, … everything that is me, is in all respects different … to any other Being … that either is now … or in all probability that ever will exist in the whole Universe.

(Quoted in Dinkel, 1983, p.9)

But although the prince's Chinese interiors clearly satisfied his desire for distinctiveness, the Chinese style was conspicuously unfashionable by comparison with the rage for the Egyptian or the Greek (mostly inspired by Nelson's victorious Nile campaign and the researches of Napoleon's invading archaeologists), or even the picturesque Gothic.

The Chinese was, frankly, vulgar at this juncture, associated with London's famous public pleasure-grounds, Vauxhall and Ranelagh. Although it promptly came back into fashion, that was because the prince had espoused it. Two explanations for this surprising choice can be advanced. One is personal: that the style satisfied George's nostalgia for ‘the forbidden masquerades and the festive amusements of his youth’ (Dinkel, 1983, p.30).

The other possible explanation is that the dream of enlightened despotism and secure hierarchy so encoded in eighteenth-century aristocratic views of the Chinese may have been peculiarly congenial to a prince now leaning towards Toryism in the troubled aftermath of the French Revolution. At the exact moment, then, that Napoleon was playing with images of authority in his efforts to invent himself as emperor, the prince was also playing with representations of his power.

A sharpened nostalgia for the endangered and perilous splendours of absolute monarchy could be played with and played out in games of defiantly extravagant style, sourced from accounts of Lord Macartney's embassy to the Emperor Ch'ien Lung in 1792, lavishly illustrated by William Alexander.

The effect seems, however, to have been ambiguous if we are to believe one of the prince's slightly puzzled visitors: ‘All is Chinese, quite overloaded with china of all sorts and of all possible forms … the effect is more like a china shop baroquement arranged than the abode of a Prince’ (Lewis, 1865, vol.II, p.490).

‘Baroquement’ signifies ‘in a Baroque fashion’: the commentator means that the china is piled up in an elaborate, ornate and rather overpowering arrangement, very different from neoclassical simplicity, symmetry or elegance.

In the next section we'll look in more detail at how the illusion of Chineseness is created in these interiors, and at the evolution of the prince's Chinese interiors from Enlightenment chinoiserie to a full-blown, stage-set, Romantic version of the East.