3 Britain in the 1790s

A problem that has exercised historians for many years is, put in its most concise form: why was there no revolution in Britain in the 1790s? The question is a significant one here, because religious factors have formed an important strand in the answers that have been given. The intellectual trend was set by the publication in 1913 of England in 1815, in which the French historian Elie Halévy (1870–1937) argued that the growth of Methodism in this period was a key factor in the British avoidance of revolution. Later scholars gave their attention not only to Methodism but also to the role of the wider Evangelical movement, including Wilberforce and Evangelicals within the Church of England (e.g. V. Kiernan, 1952, ‘Evangelicalism and the French Revolution’, Past and Present, pp. 44–56). In 1984 the view was again advanced that ‘evangelicalism… may, at least for some, have averted a potentially dangerous build-up of frustration and political discontent’ (I.R. Christie, 1984, Stress and Stability in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain: Reflections on the British Avoidance of Revolution, Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 213–14). The scholarly debate here is too complex and protracted to develop here. Nevertheless, some points are worth highlighting with respect to the discussion of Wilberforce’s writings.

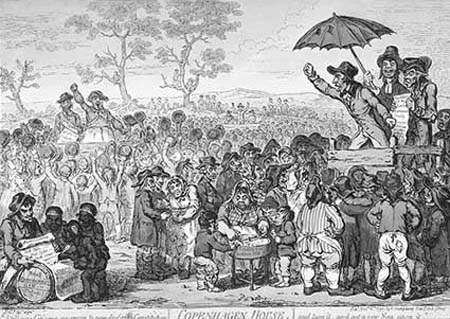

The 1790s were indeed a period of substantial social and political stress. At just the time the French Revolution broke out, the so-called ‘Industrial Revolution’ was gathering momentum, with associated rapid population growth, over-crowded and squalid living conditions, and reorganisation of traditional patterns of work and daily life. Supplies of food were sometimes erratic, giving rise to riots in 1795–6 and again in 1800–1. The outbreak of war led to substantial depression and unemployment because of the loss of export markets. Those in traditional industries such as handloom weaving, whose livelihoods were being threatened by the growth of new and more efficient technologies, experienced particular hardship. There were also significant ideological and organisational rallying points for those discontented with the existing order. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) advocated the foundation of society on an Enlightenment conception of ‘natural rights’ rather than on the basis of historical patterns and precedents. Paine believed that such a vision was currently being realised in France. Radical Dissenters campaigned for civil equality with Anglicans. During the early 1790s there was a substantial movement of popular radical societies campaigning for political reform, centred on the London Corresponding Society (Figure 2) and, at its peak, having a presence in more than 80 English towns and cities. North of the border a General Convention of the Friends of the People in Scotland met in 1792. Apart from an extreme fringe, this was a movement for peaceful constitutional change rather than violent revolution.

It was also strongly and effectively opposed at a popular level by loyalist’ organisations that upheld the existing social and political structure. Nevertheless, conservatives were alarmed by the mere existence of popular radicalism, given the backdrop of revolution and war on the Continent and occasional instances of riot and unrest at home. Pitt’s government responded vigorously, prosecuting some radical leaders and in 1794 suspending habeas corpus, enabling them to hold suspected agitators without trial. In late 1795 it rushed through legislation extending the definition of treason to include any attempts to intimidate the government or Parliament, and banning ‘seditious’ meetings of more than 50 people. Wilberforce himself made a dramatic dash to York at the beginning of December 1795 to speak at a Yorkshire county meeting in defence of the government’s policy, arguing that it was not repression but a necessary safeguard of true balanced liberty.

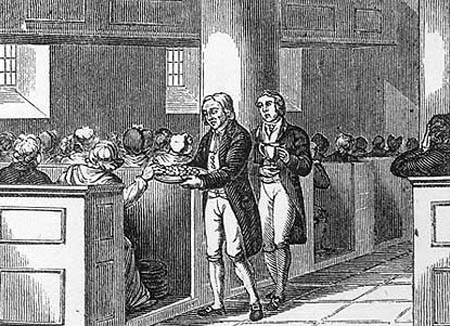

The 1790s also saw a rapid growth in Evangelicalism. Methodist membership increased from 56,605 in 1791 to 91,825 only a decade later. These figures almost certainly substantially understate the numbers of those influenced by Methodism by attending meetings, worship and preaching but not formally becoming members. Although there were some radical leanings within Methodism, as reflected in a split leading to the formation of the Methodist New Connexion in 1797, the great majority of the movement was conservative or at least apolitical (Figure 3). In his Making of the English Working Class (1963) E.P. Thompson emphasised the role of Methodism both in reconciling the poor to industrial work discipline and in deflecting them from revolution by turning their hopes for a better world towards the next life rather than this one.

Evangelicalism was also expanding elsewhere. The numbers of Baptists and Congregationalists (two of the main groups of Protestant Dissenters whose forbears left the Church of England in the seventeenth century), many of whom were influenced by the movement, grew by more than a third between 1790 and 1800. Although Evangelicals remained a small minority within the Church of England, they were nevertheless gaining ground. Wilberforce was one of a small but influential circle of prominent lay converts, who provided respectability and substantial financial resources. Moreover, even before the publication of A Practical View, a substantial Evangelical literary contribution was coming from the pen of Hannah More (1745–1833), a Bristol-based writer and teacher (Figure 4). Her Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great (1788) anticipated Wilberforce by criticising the elite for their failures of morality and social responsibility. In a series of tracts directed at the lower classes beginning with Village Politics (1792), she diffused an anti-revolutionary message extolling the virtues of a well-ordered society. These publications were very widely distributed during the 1790s.