4 Wilberforce’s A Practical View

4.1 The impact of A Practical View

A Practical View is significant both as a kind of ‘manifesto’ by a prominent figure in a religious movement of rapidly expanding influence, and as part of an ongoing process of reflection on the state of British politics and society in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Wilberforce had been working on it intermittently for four years before its eventual publication on 12 April 1797. As a busy politician he struggled to find the time for sustained writing. He had initially had a pamphlet in mind, but the project grew in the making, and the book when it appeared was a substantial one of 491 pages. It has a somewhat rambling style: Wilberforce was prone to write as he talked, offering much eloquent rhetoric and lively insight, but he had neither the time nor the inclination for systematic and tightly structured thinking. Wilberforce’s underlying concern was to communicate what he believed to be the essential features of biblical Christianity to his contemporaries, first inspiring a commitment to ‘real Christianity’ in them, and thereby transforming the moral, political and social state of the nation. The work was an immediate success, selling 7,500 copies and being reprinted five times within six months of its publication. It went through nine English editions by 1811 and 18 by 1830. It was published in the United States in 1798, and translated into French in 1821 and Spanish in 1827.

In the opinion of Daniel Wilson, a prominent Evangelical clergyman in the next generation, ‘Never, perhaps, did any volume by a layman on a religious subject, produce a deeper or more sudden effect’ (‘Introduction to Wilberforce’s Practical View 1829, p. xvii). Its appeal was attributable in part to the prominence of its author, both as politician and as Evangelical leader, and in part to its offering of a vision for personal and national salvation at a time of considerable insecurity. In the spring of 1797 Britain found itself completely isolated in the war against France. Then, within a few days of the publication of A Practical View, a series of naval mutinies broke out in the fleets stationed in Spithead off Portsmouth and in the Thames estuary. In 1798 there was a rebellion in Ireland. These years were perceived by some at the time and since as a moment of real danger of revolution. In this context any book that offered a diagnosis of underlying national difficulties and a possible solution to them was likely to attract considerable interest.

Click to view The Introduction to A Practical View [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Exercise 1

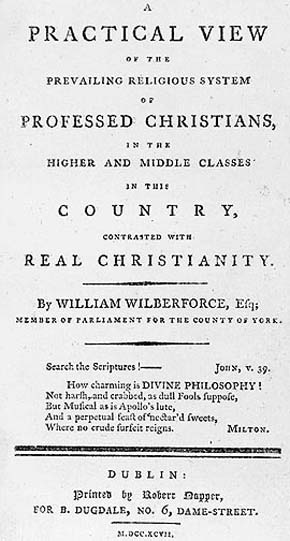

Look at the illustration of the frontispiece, including the full cumbersome title (Figure 5), and read the Introduction to A Practical View in the attached pdf (above), then write answers to the following questions:

-

What image of himself do you think Wilberforce wanted to project through the book?

-

What further insights do you gain into his motives for writing it?

Discussion

-

Wilberforce is consciously trying to portray himself as both seriously concerned about religion and as an active public figure. His name and his position as ‘Member of Parliament for the County of York’ boldly appear on the title page. He is not sheltering behind the anonymity common among authors at this period, but deliberately using his own name, status and reputation as a means to arouse interest in the book. He is apologetic that ‘busyness’ deprives him of the opportunity for ‘undistracted and mature reflection’, but makes a virtue out of his lay status, which means that he cannot be accused of having a professional interest in promoting religion. His ‘view’ of the state of religion in the country is to be that of a ‘practical’ man, distinguished from the abstract theology written by the clergy.

-

The title immediately establishes Wilberforce’s central – and characteristically Evangelical – preoccupation with the dichotomy between ‘real’ and nominal Christianity. It also identifies his target as the ‘higher and middle classes’: while Wilberforce was worried about the spiritual and social state of the lower classes as well, he is not primarily concerned with them in this book. His overriding motivation is a spiritual one, calling his contemporaries to respond to the call of ‘real Christianity’ in this life before they have to face the judgement of Christ in the next. At the same time, though, he also believes religion to be ‘intimately connected with the temporal interests of society’, and accordingly that his work has an immediate relevance to the current political situation.