1 Reading the English Bible

By Bob Owens

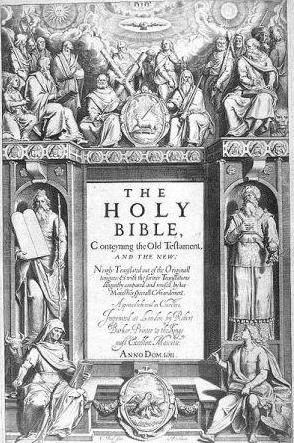

The year 2011 marks the 400th anniversary of the publication of the most widely-read book in the English language: the translation of the Bible published in 1611 that has come to be known as the ‘Authorised Version’ or the ‘King James Bible’.

For more than 300 years this was the Bible people heard read in church every Sunday, and indeed it remained the best-selling Bible in the United States right up to the 1980s. It was not the first translation of the Bible into English. William Tyndale’s pioneering translation of the New Testament had appeared in 1526, but before he could complete the Old Testament he was hunted down and put to death as a heretic. In the sixteenth century, religious and secular authorities were very nervous about the idea that ordinary people should be allowed to read the Bible freely for themselves, and it was only in the Elizabethan age that Bible reading became at all widespread.

Vast numbers of copies of the authorised version of the Bible circulated from the seventeenth century onwards, in all kinds of formats – large and small, expensive and cheap. But how exactly did people read this most important of all books? And what impact did Bible reading have on them? There are many records in the UK RED site of Bible reading – nearly 1000 in total, and the number grows all the time. These enable us to explore the many different ways in which readers engaged with the Bible over the centuries.

Diaries are a prime source of evidence. In the diary kept by Puritan clergyman Isaac Archer from 1641 to 1700, he records that as an undergraduate at Cambridge he was ‘diligent in reading the scriptures every day’, and had read through the whole Bible each year for three years in succession, ‘according to Mr Byfield’s directions’ (UK RED: 22125 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ).

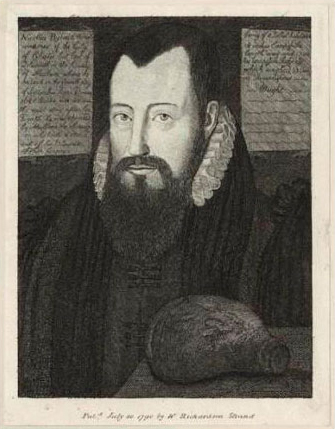

The ‘Mr Byfield’ here is Nicholas Byfield, author of Directions for the Private Reading of the Scriptures, first published in 1617, which included a calendar setting out which chapters are to be read each day, so that the entire Bible can be read from beginning to end over the course of one year. This piece of evidence shows how reading behaviour could be influenced by the advice given in books of instruction such as Byfield’s. Archer’s devotion to Bible reading was by no means unique. The diary of William Upcott, a bookseller’s assistant in the nineteenth century, reveals that he read about ten chapters of the Bible every morning and every evening (UK RED: 5917 and UK RED: 5918), and many similar examples can be found.

The most famous diarist on the UK RED site is Samuel Pepys. He is a wonderful source of evidence about reading, mainly because the information he gives is so precise. In his diary for Sunday 5 February 1660 (UK RED: 11620), to take just one example, he describes how, sitting beside his wife among the congregation in St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, London and feeling bored, he took up the Bible and ‘read over the whole book of the story of Tobit’. Pepys was evidently reading the text silently, but in public, among company. Although full of detail about the reader, the location, and the text being read this entry leaves many questions unanswered. Why did Pepys choose this particular part of the Bible? How exactly did he engage with the text: was he reading it purely for the story, or was he discovering deeper meanings in it? We can make some guesses in attempting to answer these questions. The Book of Tobit is included in the Apocrypha, the collection of books which up to the early nineteenth century was always included between the Old and New Testaments in the Authorized Version. It is an entertaining tale, with a fast-moving and eventful plot, and a cast of vividly drawn characters. It seems like just the thing to take Pepys’s mind off ‘a poor sermon’, and we might guess that he was reading Tobit more for literary pleasure than spiritual edification.

Bible reading was by no means only an activity for adults, and indeed in the past it was often the first book a child was given to read. In her Autobiography, written in 1855 and published in 1877, the feminist writer Harriet Martineau recalls her incessant early reading and study of the Bible (UK RED: 6622), describing how she made ‘Harmonies’ of the four gospels, and how much she was influenced by ‘the moral beauty and spiritual promises I found in the Sacred Writings’.

By contrast, it was the illustrations in the huge family Bible that sparked the imagination of the young Thomas Jackson: ‘There was one of Joshua’s army storming a hill fortress – with the great iron-studded door crashing down before the onrush of mighty men with huge-headed axes – that never failed to thrill’ (UK RED: 11442). What this entry reveals is how, even in a book as important as the Bible, features such as illustrations may be as important as the words themselves in determining the impact books make on readers.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.