2 Charles Dickens and his readers

By Mary Hammond

Love him or hate him, it is widely accepted now that Charles Dickens was one of the giants of Victorian literature, far outselling his rivals and thus – so the story goes – exceptionally far-reaching in his power and influence. But how much influence did he really have, and on whom? Do healthy sales figures always equate to widespread enjoyment by readers? Evidence from the UK RED site gives us some diverse and often surprising answers.

Some entries support the common claim that working-class readers were particular fans of Dickens. East-Ender George Acorn was punished by his parents for wasting 3½d on a second-hand copy of David Copperfield, but later changed their minds by reading the saddest passages aloud to them (UK RED: 2368 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ). Arthur Harding, a Victorian professional criminal, enjoyed A Tale of Two Cities and Dombey and Son when he read them in prison (UK RED: 5220), and another inmate, a fruit seller turned petty crook, was a Dickens expert who could perform any one of his characters on demand (UK RED: 12545). Similarly, while imprisoned in Reading Gaol in 1901, labourer Stuart Wood cried himself to sleep every night with ‘fellow sufferer’ David Copperfield in his arms (UK RED: 12644).

But the UK RED site also shows us that not all working-class readers felt the same about Dickens. One group of schoolboys being read A Christmas Carol by their teacher in the depressed steelworks town of Merthyr Tydfil between the two World Wars could not understand why Bob Cratchit was supposed to be hard done by when he had a perfectly good job (UK RED: 5222). And Norman Nicholson, son of a tailor, reading The Old Curiosity Shop and The Chimes in the 1920s, felt that ‘they were enough to sour a boy against the novels for the rest of his life’ (UK RED: 11378).

Women readers prove equally divided. Mary Russell Mitford, reading The Chimes in 1844, wrote to her friend Elizabeth Barratt Browning that she didn’t like it at all (UK RED: 17605), and received a letter in return in which Elizabeth claimed it had ‘touched me very much! I thought it and still think it, one of the most beautiful of [Dickens’s] works’ (UK RED: 17606).

Further, despite the common claim that he united Victorian families in the practice of shared reading, Dickens actually sometimes divided them. The mother of Thomas Jackson despised Dickens and suggested that her son read Thackeray as an antidote to the novels recommended by his Dickens-mad father (UK RED: 11444).

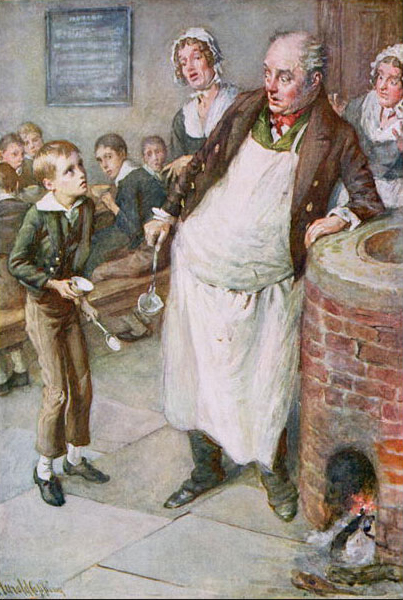

Children themselves had mixed opinions. The Victorian critic Andrew Lang recalled that as a child he used to be a swot, but being introduced to Dickens made him drop dull text-books for good (UK RED: 3213). Growing up in New Zealand in the late 1890s, Katherine Mansfield claimed with some pride that she could make the other girls cry when she read Dickens’s novels aloud in sewing class (UK RED: 3831). Several writers claim that it was reading Dickens as children that set them on their literary paths (UK RED: 3203; UK RED: 11249; UK RED: 17006), and his works had the still worthier effect of making the young R. L. Stevenson want to ‘go out and comfort someone’ (UK RED: 17574). But Vera Brittain was never able to read Dickens again after being read aloud to by her mother (UK RED: 20890), and when A. A. Milne, the future author of the Pooh stories, read Oliver Twist at the age of nine it gave him nightmares (UK RED: 3206).

As well as recording disagreement among readers, entries in RED demonstrate the many different ways in which people read and the different needs reading can fulfill. In the 1850s novelist Elizabeth Gaskell read a bit of Little Dorrit over the shoulder of a fellow passenger on the bus and was frustrated that she had to get off before her companion turned the page (UK RED: 19152). In 1901 Newman Flower, later head of Cassell’s publishing house, rose at 4am to watch the funeral procession of Queen Victoria pass by and whiled away the hours of waiting by reading Bleak House, then got so engrossed in his book that he totally missed the cortege (UK RED: 3202). Victorian girls Mary Paley Marshall (UK RED: 4711) and H. M. Swanwick (UK RED: 4727) were both forbidden Dickens’s novels by their parents, but read them in secret anyway. Lady Charlotte Schreiber could only read him in small doses (UK RED: 7788), but Donald Hankey, an Army Subaltern, found that Dickens cheered him up no end when he was ill (UK RED: 10305). Virginia Woolf likewise found the ‘magnificent’ David Copperfield helped her headaches (UK RED: 7862), while her husband Leonard found Pickwick amusing while riding through the wilds of Ceylon (UK RED: 19790). Katherine Mansfield found reading Dickens in bed refreshed her after a hard day’s writing (UK RED: 3786).

Some readers changed their minds about Dickens. The novelist Elizabeth Bowen ‘devoured’ Dickens as a child but found she could not read him as an adult (UK RED: 18770). Sir Walter Raleigh, Professor of English Literature at Oxford during the early part of the twentieth century, re-discovered Dickens years after he’d stopped teaching him and was caught up anew ‘in a flame of love and admiration’ (UK RED: 3229). But some were never admirers at all. For John Ruskin in 1874, American Notes was ‘dreadful beyond words’ (UK RED: 26067) and ten years later he still thought Dombey and Son ‘abominable’. Arnold Bennett, writing in the early twentieth century, agreed; ‘Nicholas Nickleby wasn’t so bad in its crude, posterish way’ (UK RED: 19221), he admitted, but The Old Curiosity Shop was ‘rotten vulgar, un-literary [and, biggest insult of all] . . . Worse than George Eliot’ (UK RED: 13036).

A best-seller Dickens certainly was, but the remarkable evidence in RED shows us the complexity and variety of his readers far beyond the story book sales can tell. And as a bonus, it reminds us how many habits and opinions we share with readers of the past.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.