4 A famous novel and its readers: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847)

By Rosalind Crone

‘Reader, I married him…’ These four words have become one of the most famous phrases in the English-speaking world, and many will be able to identify them as the opening to the final chapter of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Over the last 150 years, Jane Eyre has enjoyed a firm place in the English literary canon. Not only does it remain on the best-selling list, but in many schools children are required to read Jane Eyre as part of their literature studies. For those young readers, the description of the infamous Lowood School no doubt captures their attention; but for adults, its gothic overtones and poignant love story are truly evocative. Yet the publication of Jane Eyre was marked by controversy; not all readers foresaw that the novel would become one of the great classics of the nineteenth century.

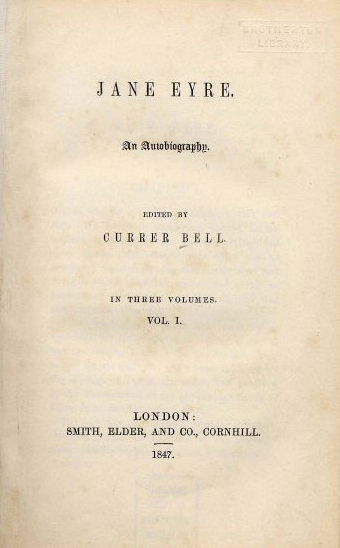

Although the first manuscript Charlotte Brontë sent to the publishers Smith, Elder & Co. was rejected, the encouraging comments from the editors convinced her to send in a second, ‘Jane Eyre: an Autobiography’, under the pseudonym ‘Currer Bell’. In his memoirs, George Smith, a partner in the firm, remembered receiving the manuscript:

The MS. of “Jane Eyre” was … brought it to me on a Saturday ... after breakfast on Sunday morning I took the MS. of “Jane Eyre” to my little study, and began to read it. The story quickly took me captive. Before twelve o’clock my horse came to the door, but I could not put the book down ... Presently the servant came to tell me that luncheon was ready; I asked him to bring me a sandwich and a glass of wine, and still went on with “Jane Eyre” ... before I went to bed that night I had finished reading the manuscript. (UK RED: 4370 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] )

Needless to say, Jane Eyre was published, as a three-volume work on 19 October 1847, and quickly became a best-seller. Its rise to fame was, in part, driven by the tremendous curiosity it provoked among readers as to its authorship. Who was Currer Bell? And was Currer Bell in fact a woman? Lord Morpeth, for instance, wrote in his private papers, ‘very powerful & interesting, in parts very fine, not altogether pleasing — some striking delineation of character; it is said to be by a woman, but it is not feminine — I should certainly say by a Socinian — not by Miss Martineau’ (UK RED: 28531). And he was certainly right about that, as Harriett Martineau herself wrote to Fanny Wedgwood in February 1848, ‘Can you tell me about “Jane Eyre”, – who wrote it? I am told I wrote the 1st vol: and I don’t know how to disbelieve it myself, – though I am wholly ignorant of the authorship … it is surely a very able book (outside of what I could have done of it) and the way in which the heroine comes out without conceit or egotism is, to me, perfectly wonderful’ (UK RED: 9171).

Great fame produced a demand for reviews. After receiving a copy of the book from the publisher, George Henry Lewes wrote to Elizabeth Gaskell that ‘the enthusiasm with which I read it made me go down to Mr Parker, and propose to write a review of it for Fraser’s Magazine’ (UK RED: 28478). But Lewes’s enthusiasm was not shared by all. Several reviewers condemned Jane Eyre, mainly because they saw in the character of Jane, and her relationship with Rochester, a challenge to societal norms regarding the place of women and morality. For instance, the critic for the Quarterly Review declared that the novel exhibited that ‘tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine’. It would only be natural that an author reading such reviews of their work would feel disheartened, and Charlotte Brontë wrote to her publisher on 17 November 1847, ‘The Spectator seemed to have found more harm than good in Jane Eyre, and I acknowledge that distressed me a little’ (UK RED: 28479). But for the most part, Brontë accepted the criticism in good humour, responding to critics’ comments on her identity with wit and strength: ‘The literary critic of [the Economist] praised the book if written by a man, and pronounced it “odious” if the work of a woman. To such critics I would say, “To you I am neither man nor woman – I come before you as an author only. It is the sole ground on which you have a right to judge me – the sole ground on which I accept your judgement’ (UK RED: 28652).

Controversy also emerged over the autobiographical content, promised on the title-page, and in part delivered as Brontë drew upon some of her own experiences to shape the story. As she wrote to the publisher in January 1848, ‘Jane Eyre has got down into Yorkshire; a copy has even penetrated into this neighbourhood: I saw an elderly clergyman reading it the other day, and had the satisfaction of hearing him exclaim “Why – they have got ––– school, and Mr ––– here, I declare! And Miss –––’ (UK RED: 4376). But if Brontë delighted in their recognition of the connections, it also sparked a long running dispute in the press as the son of Mr Carcus Wilson, founder of Cowan Bridge School, the inspiration for Lowood, desperately tried to clear his father’s name.

But despite these flash points in its reception history, for the majority of readers Jane Eyre provoked pleasure, not outrage, and it inspired Brontë’s literary peers to speak of her in the same breath as Austen, Edgeworth, Trollope and Dickens. And its appeal has proved timeless. Just as the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray declared in 1847 that the book ‘made me cry, to the astonishment of John who came in with the coals’ (UK RED: 4371), so Hilary Spalding, a young girl, wrote in her diary in 1927, ‘am reading Jane Eyre, and adore it’ (UK RED: 6644).

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.