2.2 Unity and conflict

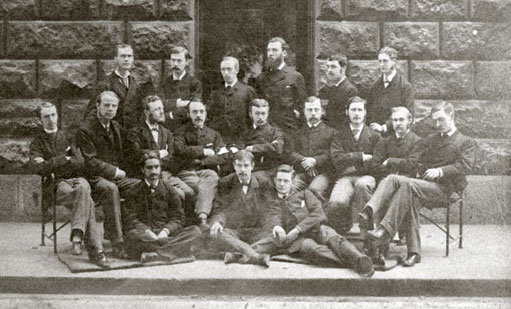

In the nineteenth century, licensing reform and developments in medical education brought a new unity to the profession. Students had a similar education, trained in large groups and developed a strong sense of allegiance to their institutions and to their teachers (see Figure 1). Links formed at medical school were maintained after graduation, with former students keeping in contact, calling on each other for help with operations and consulting each other or their former teachers on difficult cases.

This sense of a collective identity – of belonging to a body of practitioners with similar patterns of work and common interests – was greatly strengthened by the many new medical societies and journals founded in the nineteenth century. Medical journals were most popular in Britain, where more than 400 new titles were launched during this period. One of the first and most successful was the Lancet, founded in 1823 by Thomas Wakley (1795–1862), a general practitioner with a real flair for firebrand journalism. The Lancet served as a model for many other journals, including the London Medical Gazette (1827) and the Provincial Medical and Surgical Journal (1849), which became the British Medical Journal in 1857 (Bynum et al., 1992). Medical journals were founded in rather smaller numbers in Europe at the same time – in France, Germany and Belgium, where the Scalpel (surely in homage to Wakley's Lancet) appeared. Even in Russia, twenty-three new journals were established around the middle of the century.

Nineteenth-century medicine had a form and character that was unique to its time. By the end of the century, there is a stronger case for seeing medicine as a profession. Practitioners formed a more cohesive group, sharing the same forms of education, qualifications and codes of ethical behaviour. They enjoyed the status of experts, and had greater (though by no means total) control over licensing. However, they still had no monopoly of practice.

Did these changes come about through a process of professionalisation or reform? There is no clear answer. On the one hand, nineteenth-century practitioners wanted to be seen as members of a profession, distinguished by gentlemanly codes of behaviour. This may have encouraged the development of medical ethics. On the other hand, change was also driven by economics. The key attribute of modern professions – the possession of a body of specialist knowledge – was also a means by which individual students could ensure that they would succeed in practice. However, as the experience in many European countries shows, governments also had an interest in driving up educational standards in order to ensure that their populations had access to well-trained practitioners. The role of social, cultural, economic and political contexts in shaping the development of the medical profession remains poorly understood. Professionalisation occurred right across Europe – from Russia and Norway to Britain, France, Holland, Belgium and Germany – and in each nation, licensing standards were pushed up, practitioners developed a strong collective identity and they were concerned with their low status. Why this should have happened at the same time under widely differing political regimes and against different cultural backgrounds remains a puzzle for future historians.