The history of ‘othering’ and lesbianism in Britain

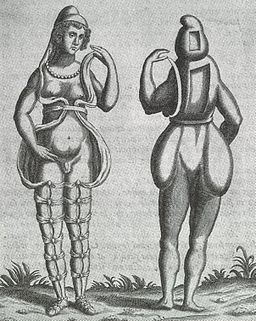

Engraving representing contemporary ideas on hermaphroditism, circa 1690.

In her book Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668-1801, the Irish novelist Emma Donoghue has written a lively account of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British lesbian culture. Unsurprisingly, she couldn’t find a single subjective account of British black lesbian experience. However, what she does show is that in the past, medical treatises, anti-masturbation manuals, cases brought to law courts, popular ballads, erotica and travel writing had a persistent tendency to ascribe lesbianism to ‘other’ nations. This is certainly clear from the writings of seventeenth-century poets (including Alexander Pope) and prose writers, who often drew on Ovid’s epistles to suggest that the Greek poet Sappho was the ‘inventor’ of lesbian sex. Further than this, though, medical texts like Jane Sharp’s The Midwives Book (1671) called lesbian sex ‘a hermaphrodites’ practice’, and claimed there were many hermaphrodites in Asia and Africa, though Sharp herself ‘never heard of but one in this country’.

Engraving representing contemporary ideas on hermaphroditism, circa 1690.

In her book Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668-1801, the Irish novelist Emma Donoghue has written a lively account of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British lesbian culture. Unsurprisingly, she couldn’t find a single subjective account of British black lesbian experience. However, what she does show is that in the past, medical treatises, anti-masturbation manuals, cases brought to law courts, popular ballads, erotica and travel writing had a persistent tendency to ascribe lesbianism to ‘other’ nations. This is certainly clear from the writings of seventeenth-century poets (including Alexander Pope) and prose writers, who often drew on Ovid’s epistles to suggest that the Greek poet Sappho was the ‘inventor’ of lesbian sex. Further than this, though, medical texts like Jane Sharp’s The Midwives Book (1671) called lesbian sex ‘a hermaphrodites’ practice’, and claimed there were many hermaphrodites in Asia and Africa, though Sharp herself ‘never heard of but one in this country’.

Most of all, there was an early and strong association of lesbian sexuality with Orientalism. In 1684, the French baron J.B. Tavernier’s Collections of Travels Through Turkey into Persia and the East-Indies was translated into English. Tavernier’s account of Turkish ‘seraglios’ – as European works of this time called the women’s quarters in Middle Eastern homes – explicitly situated lesbian sexuality as a ‘vice’ of the East. (It is also framed simply as a reaction to male homosexuality: in the absence of virile heterosexual men, women turn to each other, rather than this being a normal sexual desire in its own right.)

The Fabulous Story, which is related of their [the women] being served up with Cucumbers cut into pieces, and not entire, out of a ridiculous fear least they should put them to indecent uses …. But it is not only in the Seraglio, that that abominable Vice reigns, but it is predominant also in the City Constantinople, and in all the Provinces of the Empire, and the wicked Example of the Men, who, slighting the natural use of Woman-Kind, are mutually inflam’d with a detestable love for one another, unfortunately inclines the Women to imitate them.

(quoted in Donoghue, 1993, p. 256)

Displacing anxieties about sexuality to the east reinforced pseudo-scientific theories about the inferiority and animal nature of women of colour: racism and lesbophobia reinforcing each other.There were many popular anecdotes during this time of women passing as men in order to marry women, and again they often drew on tropes of the East. One example is A.G. Busbequis’s Travels into Turkey, translated into English in 1744. Egypt was a particularly popular location for stories about ‘hermaphrodites’. Donoghue describes accounts of Spanish and Irish women, commenting on the way that displacing anxieties about sexuality to the east reinforced pseudo-scientific theories about the inferiority and animal nature of women of colour: racism and lesbophobia reinforcing each other.

We can see clearly the tangled vilification of sexuality, race and other nationalities depicted in the eighteenth-century satirical text, William King’s The Toast. Members of the Irish aristocracy are derided here, including the Duchess of Newburgh, portrayed as ruling ‘a social circle of tribades in Dublin’. Someone thought to be Lady Allen is described through xenophobic slurs: ‘a little Dutch Frow’, ‘a Jewess and a Dwarf’, with ‘the Locks of a Negress half-mingled with Grey, / And a Carcase ill-moulded of dirty red Clay’.

A rare case from the Victorian era

Examples from the records continued to be extremely rare even in Victorian times. However, in 1810 a libel case was brought by two Scottish schoolteachers: Miss Wood and Miss Pirie. They sued Dame Helen Cumming Gordon who had told other parents with daughters at their school that her grand-daughter had been kept awake in the night by the two teachers. (Dame Cumming Gordon’s grand-daughter shared a bed with Miss Pirie in one of the dormitories – a normal practice in boarding schools at the time.) Dame Cumming Gordan’s grand-daughter was sixteen at the time, the daughter of Dame Cumming Gordon’s deceased son and an Indian woman to whom he was not married. The case was decided in the teachers’ favour. The young girl’s race and illegitimacy clearly influenced the outcome of the case. Faderman (1981) says: ‘The judges suggested that Miss Cumming, having been raised in the lascivious East, had no idea of the horror such an accusation would stir in Britain’ (p. 148). One of the judges (Lord Meadowbank) insisted that no woman in the United Kingdom would have a big enough clitoris for the penetrative tribadism he had heard was common in India.

Very real fears about the dangers of a combination of racism and homophobia mean that even if there had been collective celebratory black and gay events before the 1970s, these couldn’t have been documented. Even Donoghue’s twentieth-century historical account is unusual in the efforts she made to consider issues of race and sexuality in an appropriate way. As late as the 1970s, it was normal for historians of an emerging discipline of gay studies to use a racist and orientalist tone, as this extract from Rowse’s Homosexuals in History (1977) shows:

Three years in Algeria opened his eyes – Algeria was a Mecca for all this circle: no Protestant obfuscations there. Gide [nineteenth/twentieth century French novelist] fell for a voluptuous native boy, Athman, who must have been very satisfying in contrast to Madeleine, and got his fellow-traveller, Henri Ghéon … to bring this morsel of humanity back to Paris.

(p. 186)

It is hard to imagine a serious historian writing in this way today. (The use of Mecca as a trope here is particularly inappropriate.)

Black lesbian sexuality in the 1960s/70s

One account of black lesbian sexuality during the 1960s is provided in the white writer Val Wilmer’s autobiography about her life as a photographer of jazz musicians, Mama Said There’d Be Days Like This: My Life in the Jazz World. She makes no mention of any black lesbian community or organisation. (Her account suggests there might have been small informal groups, but as a white woman these would not have been open to her.)

In 1964, Wilmer had a lesbian encounter at a party with someone she calls Yvonne, a nurse who had come over from the Bahamas. Wilmer had a more serious affair with a woman she calls Stevie Tagoe: a dancer and musician, a mixed-heritage British woman whose grandfather was a Ghanaian jazz musician. It’s worth noting that even when writing much later on, Wilmer was still not able to give Stevie’s real name. Although the ‘relationship’ lasted several years, neither of them appear to be able to take it seriously. They both had affairs, sometimes with men. They found this difficult but it seems as if in a relationship they had no means of establishing as formal or official, it wasn’t possible to talk with each other about this. Yet when Stevie went to Turkey and Ghana, or Wilmer to the States, they would travel together.

In 1969, the two women travelled to Turkey, and found a world where although lesbian relationships were scandalous, they were surreptitiously talked about:

One of the first words we learned was seviçi. Farah [the mother of the dancer with whom Stevie performed] had guessed our relationship and we soon realised this translated as ‘lesbian’. She loved to share gossip and scandal and would tell us, nudge-nudge, that this one or that one was seviçi, having us constantly in stitches.

(Wilmer, 1989, p. 195)

The Gateways club door in Chelsea, London 2007

Wilmer gives this description of the famous lesbian club, Gateways, which featured in the film The Killing of Sister George:

The Gateways club door in Chelsea, London 2007

Wilmer gives this description of the famous lesbian club, Gateways, which featured in the film The Killing of Sister George:

From time to time a few other Black women appeared, a couple of whom had the same complexion as Stevie and, I assumed from their East London accents, similar backgrounds. I noticed them eyeing her with suspicion, however, and when we did try to strike up a conversation, they made it quite clear that this was their patch and anyone in their company not for sharing.

(p. 164)

This short account vividly demonstrates the difficulties of living in a society that combined homophobia and racism, and how hard it would have been to come together in any kind of black lesbian or gay community as late as the 1960s.

The art historian Kobena Mercer has argued that during the 1970s, feminist initiatives ‘radically politicized the issue of sexual representation’ (1994, p. 133). The feminist struggle revised black politics as a project of plural identities, rather than only for black heterosexual men (what Kimberley Crenshaw would later call intersectionality). This led to an upsurge of collective action and opened up social scenes which had been primarily white, or primarily heterosexual before.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews