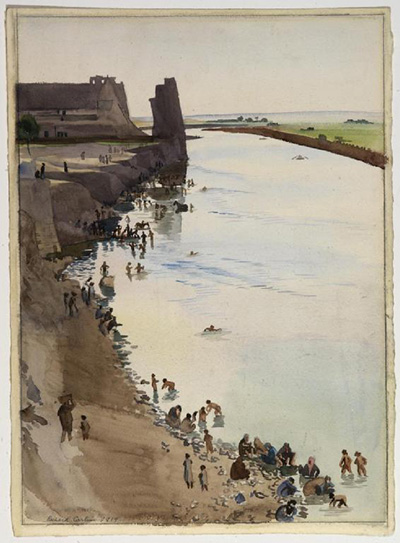

The River Tigris at Mosul, 1919

In Europe, the Armistice between Germany and the Allies began at 11.00am on November 11th 1918. Germany was the last of the Central Powers to conclude an Armistice with the Allies, as their military situation became increasingly hopeless from the summer of 1918. On 29th September 1918, Bulgaria signed the Armistice of Thessalonica. On October 30th 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed an Armistice on board the Royal Navy ship H.M.S. Agamemnon in Mudros harbour, on the island of Lemnos. On November 3rd 1918, Austria-Hungary signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti. On the Western Front, fighting continued right up until 11.00am on November 11th, as the Allied Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch refused to accept Germany’s request for a ceasefire and truce. American soldier Henry Gunther was the last man to be killed on the Western Front, being cut down by machine-gun fire at 10.59am. Despite the Armistices, the war continued in some places. Soldiers who had transferred their allegiance to newly-declared independent nation states such as Czechoslovakia switched their efforts to creating ‘facts on the ground’, attempting fix the borders of their new nation through force. In the Middle East, the Allies sought to create new political realities by taking advantage of the vacuum left by the collapse of the Ottoman armies, the most significant example being the British ‘dash’ for Mosul, after the Armistice with the Ottomans had been signed.

The River Tigris at Mosul, 1919

In Europe, the Armistice between Germany and the Allies began at 11.00am on November 11th 1918. Germany was the last of the Central Powers to conclude an Armistice with the Allies, as their military situation became increasingly hopeless from the summer of 1918. On 29th September 1918, Bulgaria signed the Armistice of Thessalonica. On October 30th 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed an Armistice on board the Royal Navy ship H.M.S. Agamemnon in Mudros harbour, on the island of Lemnos. On November 3rd 1918, Austria-Hungary signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti. On the Western Front, fighting continued right up until 11.00am on November 11th, as the Allied Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch refused to accept Germany’s request for a ceasefire and truce. American soldier Henry Gunther was the last man to be killed on the Western Front, being cut down by machine-gun fire at 10.59am. Despite the Armistices, the war continued in some places. Soldiers who had transferred their allegiance to newly-declared independent nation states such as Czechoslovakia switched their efforts to creating ‘facts on the ground’, attempting fix the borders of their new nation through force. In the Middle East, the Allies sought to create new political realities by taking advantage of the vacuum left by the collapse of the Ottoman armies, the most significant example being the British ‘dash’ for Mosul, after the Armistice with the Ottomans had been signed.

The war in the Middle East began when the Ottomans joined Germany and her allies in November 1914. It was fought on a number of fronts. Huge Ottoman armies clashed with the Russians in the Caucasus; errors by the Ottoman leaders and problems with supplying the armies led to many deaths. Ottoman forces tried and failed to take the Suez Canal, a vital waterway and strategic artery for the British empire. The British Empire’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force pushed the Ottomans out of the Sinai Peninsula, and invaded Palestine then Syria, reaching Aleppo in late October 1918. In the Hijaz, in western Arabia, Sharif Hussein of Mecca launched the Arab Revolt, aided by British officers such as T.E. Lawrence. Further south, Ottoman troops pinned down a British force in Aden until the end of the war.

The original objective of what became known as the Mesopotamian Campaign was to secure Basra and the oil refinery at Abadan, in adjacent Persia. On November 6th 1914, a British Indian Expeditionary force landed in southern Iraq. The original objective of what became known as the Mesopotamian Campaign was to secure Basra and the oil refinery at Abadan, in adjacent Persia. But ‘mission creep’ set in, and the army continued northwards. At Kut, after a series of military blunders, a British Indian force was besieged, and surrendered in April 1916. It was one of Britain’s worst military setbacks in the war; some 13,000 men became prisoners of war, and many died. The disaster at Kut led to a commission of enquiry being established that was critical of the way the British Indian army had ran the campaign. After extensive reorganisation and reinforcement, British forces resumed their advance northwards, and captured Baghdad on March 11th 1917. It was the first major British military success of the war.

After the fall of Baghdad, British forces continued a steady advance northwards, although the rapid advances of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force under General Allenby in Palestine and Syria had greater strategic and military importance. By October 30th 1918, British troops had reached al-Qayyara, 35 miles south of Mosul. In Baghdad, British administrator Gertrude Bell wrote to her mother on November 1st that “we have struck the final blow this week with an advance up the Tigris”. General William Marshall received news from the War Office that the Armistice with the Ottomans had been signed on November 1st, but only received the detailed terms the next day. Bell framed Britain’s dash for Mosul as an internal security issue: “if there is no strong hand there I fear there will be looting and massacre”, a view reflected in the campaign’s Official History. Marshall ordered his troops to push on to Mosul on the evening of November 1st. But the previous day, the commander on the spot, General Cassels, had received a letter from his Ottoman counterpart, Ali Ihsan Pasha, requesting him to return to the position he held on October 30th. Ali Ihsan’s small force held the road to Mosul. The British political officer Colonel Leachman met Ali Ihsan early in the morning of November 2nd in Mosul. Leachman told Ali Ihsan that Cassels had orders to advance and occupy Mosul, but Cassels hoped to avoid fighting the Ottomans. Negotiations continued between Ali Ihsan and the British. General Marshall then sent further orders, stating that according to the Armistice the Allies had the right to occupy any “strategical points”, and the War Office had ordered the occupation of Mosul. On November 3rd, talks continued with Ali Ihsan, complicated by the fact that the Ottoman government and the British held differing interpretations of the Clauses of the Armistice as they related to the situation on the ground in Mosul. Discussions between Admiral Calthorpe, one of the British signatories to the Armistice, and the British government in London, produced a clear response to Ottoman objections to Mosul’s occupation under the Armistice terms: the occupation was going to happen, and if the Ottoman government did not agree with this, it was going to happen “by force of arms”. General Marshall himself travelled to Mosul on November 7th, and ordered Ali Ihsan to evacuate his troops from the whole of Mosul province by November 15th. Ali Ihsan agreed to do this under protest, as he had not received orders from the Ottoman government to this effect, although these eventually arrived on November 9th. Ali Ihsan’s force began their withdrawal, and the British occupied Mosul on November 10th 1918. For those living in Mosul, the war only ended with the arrival of British troops in their city on this date.

It was only after the war that the British began to fully appreciate the extent and value of the province’s oil reserves.Why did the British occupy Mosul? A common answer to this question is because there were oil deposits in the province. However, it was only after the war that the British began to fully appreciate the extent and value of the province’s oil reserves. British wartime government files do not mention oil as a reason for the decision to occupy Mosul. The decision was made as part of a broader strategy to alter the terms of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France, which carved up a large area of the Ottoman Empire’s territories between them. Sykes-Picot assigned Mosul province to an Arab state under French protection, but what this would mean in practice was a form of French imperial rule. Having spent much blood and treasure in the Mesopotamian Campaign, British statesmen, especially Prime Minister Lloyd George and Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, did not want to simply hand Mosul over to the French. By occupying Mosul after the war had ended, British forces created ‘facts on the ground’ which would be impossible for the French to overturn during discussions around the peace treaties, which is indeed what happened.

Both the Ottoman government and its successor Turkish government under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk believed that Mosul vilayet (province) was theirs. During the negotiations with the Allies over the 1920 Treaty of Sevres and its successor the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Ottoman and later Turkish officials consistently maintained that the province had been illegally occupied and controlled by Britain. The League of Nations appointed a commission to investigate the issue, and recommended that Mosul should remain part of Iraq. This was unsurprising given Britain’s influence in the organization. A frontier treaty signed between Iraq and Turkey in 1926 formalised this decision and gave Turkey a 10% royalty on Mosul’s oil deposits for 25 years.

Britain’s actions as a result of its desire to create ‘facts on the ground’ had immense consequences for the region and its inhabitants. Mosul became part of Iraq, not Turkey. Had Mosul remained part of Turkey, the successor state to the Ottoman empire, its history would have been very different indeed.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews