1 What is art?

We need to think about how to define art before we begin to look at it more closely. It is notoriously difficult to pin down a clear definition of art, so in this course we'll be considering some fresh approaches to its study rather than providing a definitive answer to the question ‘what is art?’ Considering many different interpretations when studying texts also applies to the study of paintings, sculptures and installations. So, although I'll often follow the activities in this course with interpretations of the art works that you'll be studying, this is not intended to provide you with an answer that is better than your own. Rather, I am simply offering another interpretation which you may be able to contrast with your own. Let's start by looking at two art works.

Activity 1: Looking at two art works

Look at Plates 10 and 17 below, and make some notes for each one in response to the following questions.

Do you like it?

How does it make you feel?

Is it art? Briefly explain the reasons for your answer.

Don't spend more than a minute or two responding to each question. Questions 1 and 3 require a simple ‘yes' or ‘no’ answer and some brief explanation for question 3. For question 2 you could record your immediate feelings about the works represented, using one word answers (for example ‘happy’ or ‘confused’) rather than complete sentences.

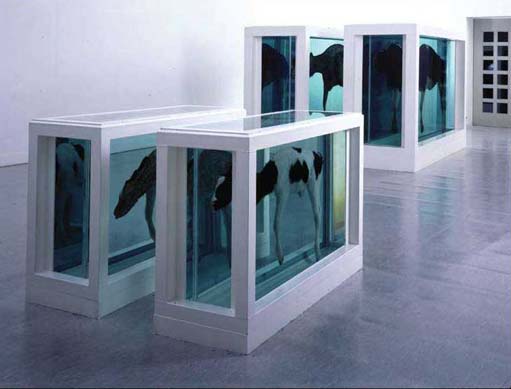

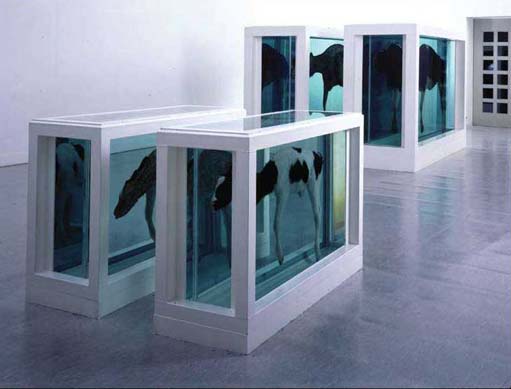

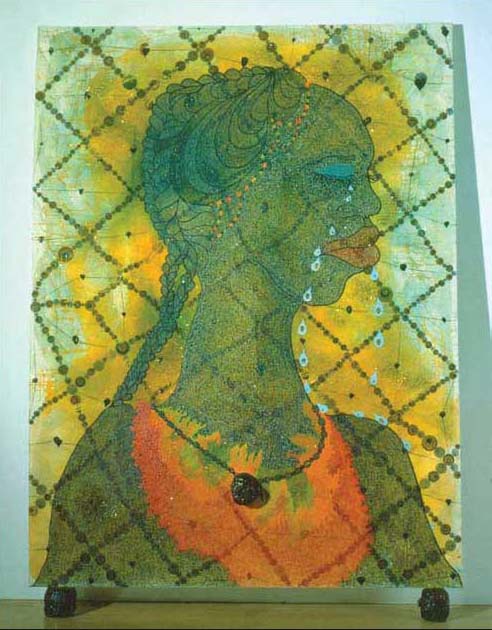

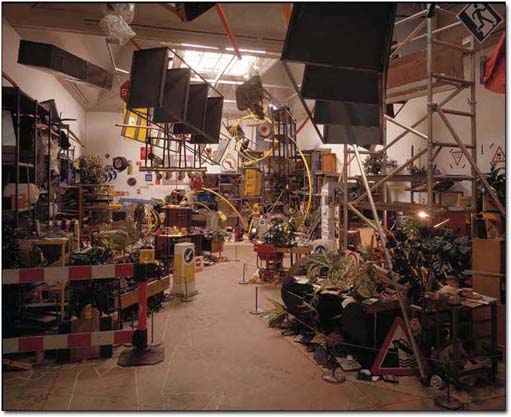

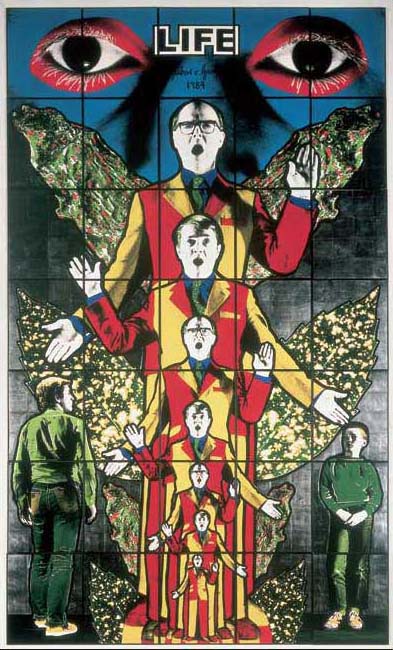

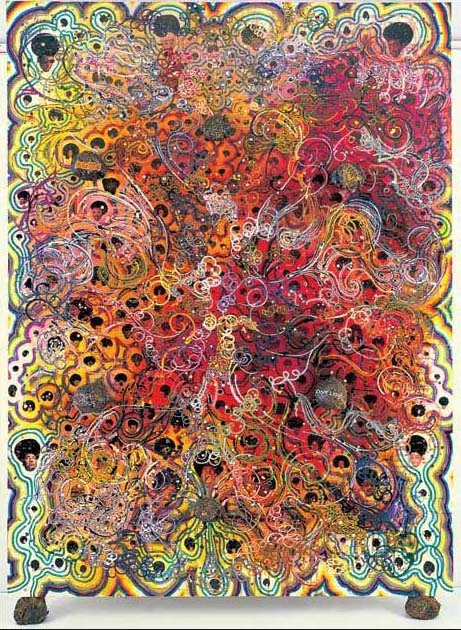

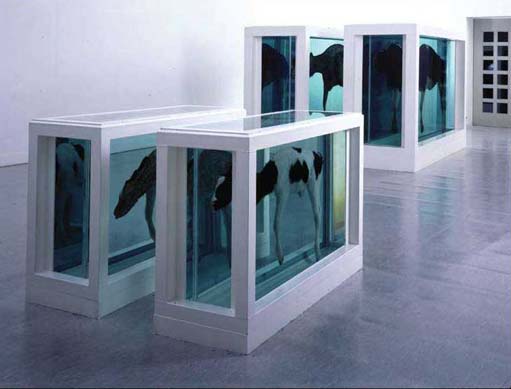

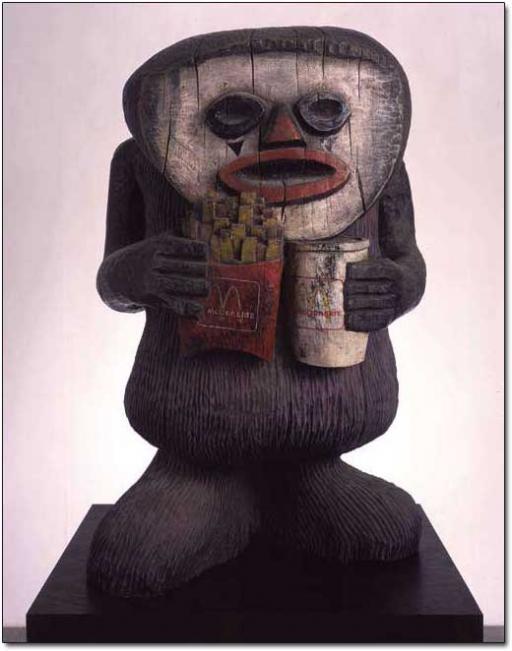

Plate 10

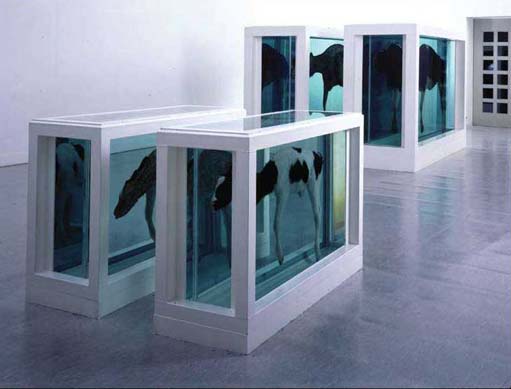

Plate 17

Discussion

Your own response to each activity will largely depend on your taste, background and personal experiences. I'm guessing, however, that for this activity, Damien Hirst's Mother and Child Divided will prompt more people to answer ‘no’ for questions 1 and 3 than will Raphael's Madonna of the Meadow. The range of answers for the second part of question 3 is likely to be particularly wide. Personally, while I feel that Madonna of the Meadow is quite peaceful and seems to convey a feeling of warmth and tenderness, I find Mother and Child Divided to be pretty disturbing and I feel uncomfortable about looking at it closely.

I tried this activity on a colleague and she confessed that Mother and Child Divided summed up all her fears about not being able to understand contemporary art. She said, 'I don't know whether I'm supposed to like it or not but don't really like to say so'.

You may already have your own feelings about contemporary art and if you have, the next activity will allow you to get them down on paper. You'll also get a sneak preview of the art works that you'll be exploring in this course.

Activity 2: Thinking about studying contemporary art

Skim through the art works below and then make some notes in response to the following question.

What are your feelings about the prospect of studying contemporary art?

Be as clear as possible here; later in the course you'll return to the notes that you've made to see whether your feelings have changed.

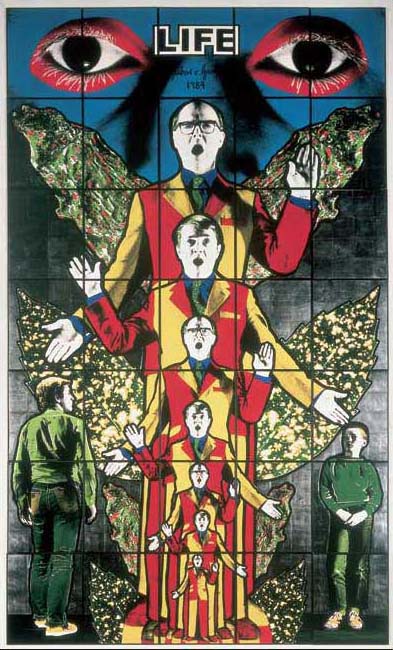

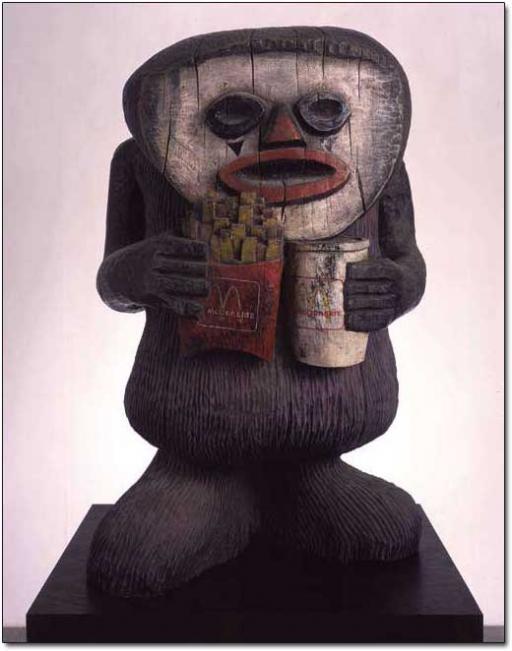

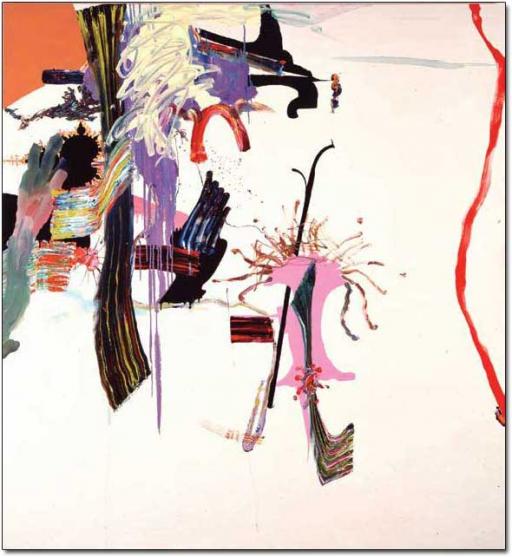

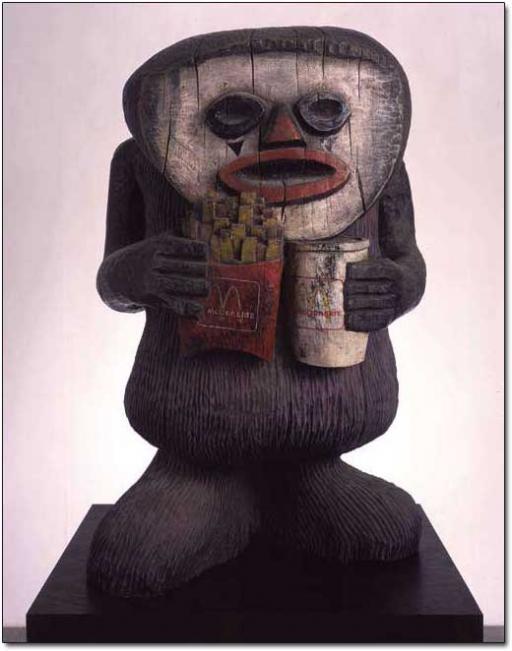

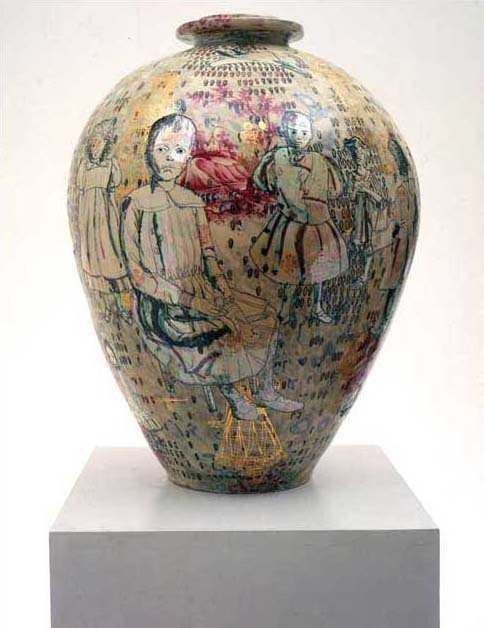

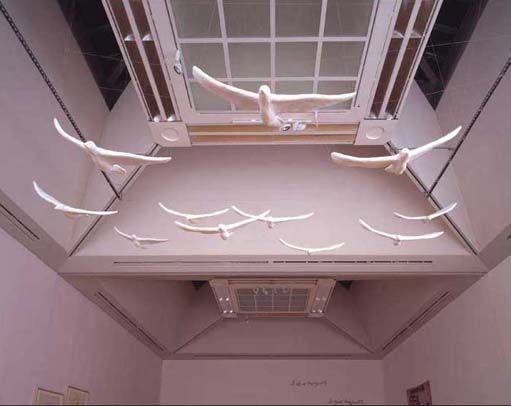

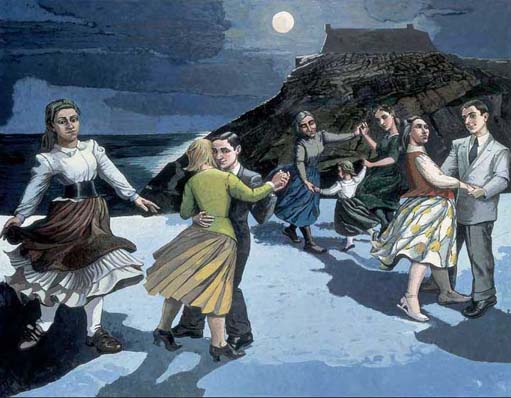

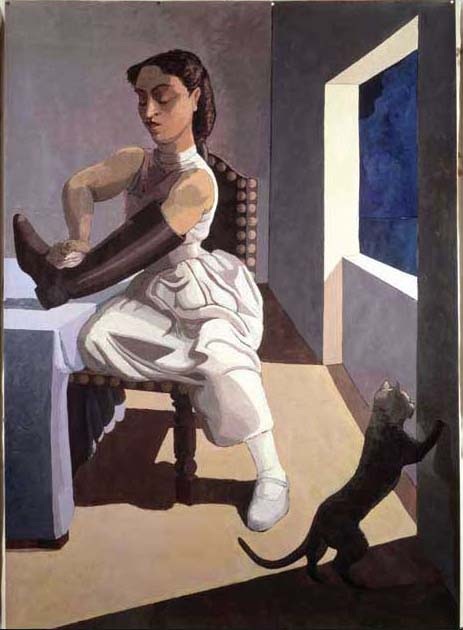

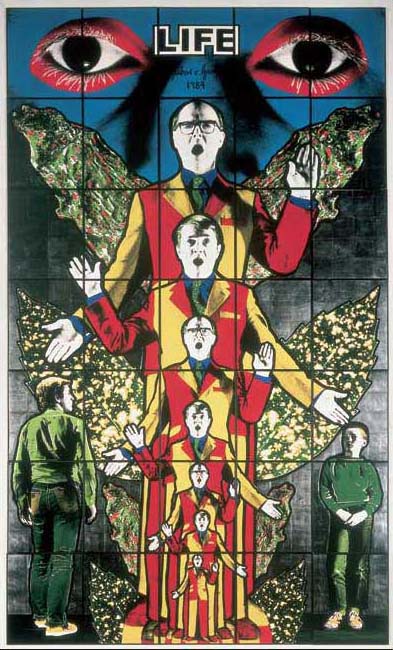

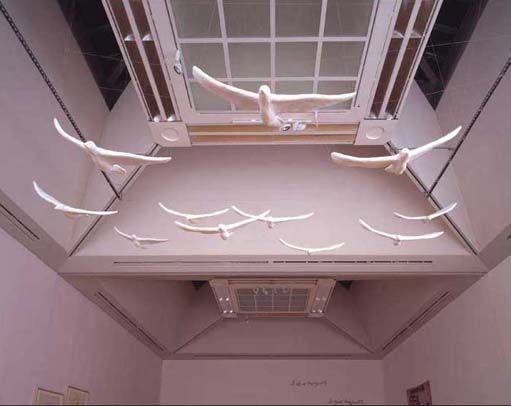

Plate 1

Plate 2

Plate 3

Plate 4

Plate 5

Plate 6

Plate 7

Plate 8

Plate 9

Plate 10

Plate 11

Plate 12

Plate 13

Plate 14

Plate 15

Plate 16

Plate 17

Discussion

Of course, since this activity is about recording your own feelings, once again there's no right or recommended answer. Maybe you're entirely comfortable about approaching contemporary art. If so, then hopefully this course will introduce some fresh ways of looking at art works produced since the 1980s. If you're in any way uneasy about studying contemporary art then I hope your study of this course will give you some pointers about how you might approach art works that seem to offer no easily identifiable meaning at first glance.

A common response to contemporary art is to query whether art works such as those reproduced in the Plates are actually art at all. This can be seen in the following comments, posted in the ‘Have Your Say’ section of the BBC News website. These comments followed a fire in a London art handlers' warehouse, in which over one hundred works were destroyed, including works by Tracey Emin (see Plates 1, 13 and 16) and Damien Hirst (see Plate 10).

Plate 1: Turner prize artists

Plate 10

Plate 13

Plate 16

I can't imagine how anyone can call a tent or a shed art. I can only assume it's because they can't paint, sculpt or turn a clay pot. This fire is no great loss to the art world …

[Gareth Dunn, Edinburgh]

Couldn't have happened to a better collection, the works of Emin and Hirst in particular. I have always thought the rubbish produced by these people would make a good bonfire. We are continually insulted by these people who tell us that if we don't love and appreciate these works then we must be stupid. I, for one, remember the fairy tale of the Emperor's new clothes …

[Kate Rodgers, West Midlands]

… I've got a few unmade beds for sale to interested bidders. In fact for the right price I'll throw in the stroppy teenage occupant. He can reduce any tidy room to the state of Tracey's bedroom if left to his own devices for a day or two.

[Karen Wood, Lincolnshire] (BBC News website, 2005)

You'll remember that in Activity 1 you were asked to consider whether Damien Hirst's Mother and Child Divided is art. If you decided that it isn't art, then you're not alone in thinking in this way. When Hirst won the Turner Prize in 1999, the prominent art critic Brian Sewell was unimpressed, commenting:

I don't think pickling something and putting it into a glass case makes it a work of art. It is no more interesting than a stuffed pike over a pub door.

(Channel 4 website, 2005)

If you concluded that Mother and Child Divided is art, then you're also not alone. Hirst has many fans, one of whom acclaimed the work as having:

The integration of thought and feeling and the combination of complexity with visual and emotional power that is characteristic of major art.

(Socialist Review website, 2005)

One reason for this difference in opinion is likely to be that the writers differ in what they think makes something art. The question ‘What is art?’ has been the subject of hot debate by art historians for many years and in the next activity you'll attempt to answer the question yourself.

Activity 3: What is art?

Make some notes about the sort of things that you consider to be ‘art’.

Make a list of any common characteristics that these ‘art works’ have. (For example, are they already exhibited in galleries, do they display technical skill, do they have the power to move you emotionally?)

Try to write a one sentence answer to the question ‘What is art?’ using your notes from Activity 1 as a basis for your response.

Discussion

Did you find this activity difficult? If so, then you're not alone. For hundreds of years people have been asking the question ‘what is art?’ and as yet no universally agreed answer has been reached. In fact, it's quite likely that there is no right answer. It's possible, though, that you might have identified some of the following as characteristics that art works tend to have in common:

being displayed in galleries

being produced by a recognised artist

showing evidence of technical skill

expressing an emotion or a point of view

being the result of a creative process by an artist

being unique

being labelled as ‘art’ by the person who created it.

The Collins Paperback English Dictionary defines art as:

'The creation of works of beauty or other special significance' and, 'Human creativity as distinguished from nature'.

(Collins, 2000)

How far does this reflect your own views? If you want to amend your own definition in the light of this, do so now.

At the end of this free course you'll revisit the question ‘What is art?’ to see if your answer to it has changed as a result of your studies. The question is also relevant to your work in the next section, where you'll begin exploring the wide range of reactions to the Turner Prize and to the art works that have been nominated for it.