1.4 The Colosseum and its meaning through time

The previous activities have given you a very brief glimpse of how studying the ancient world involves looking at different kinds of sources together. The surviving evidence from antiquity is often fragmentary, and any attempt to gain a fuller understanding of these distant cultures will usually resemble a jigsaw puzzle, as we put together different pieces of evidence and work out how they fit together. We also have to be aware of how ancient places and cultures change over time. Martial’s poem and the coin were both evidence for how the Colosseum might have been regarded when it was first built, but the meanings of the amphitheatre, and interpretations of the events that took place within it, are far from stable.

One of the most significant shifts in how the Colosseum and its games were viewed accompanied the rise of Christianity in the Roman empire. Though its spectacles remained hugely popular for a long time, objections to the violence and the way in which it transfixed an audience were registered by authors such as Tertullian who, a century or so after the Colosseum’s inauguration, condemned the arena for its dangerous incitement of passions, and the way in which it made audiences complicit in brutal punishments. Later, in the fourth century, Saint Augustine described what happened when his friend Alypius, who previously ‘held such spectacles in aversion and detestation’, was persuaded to go to the amphitheatre in Rome.

Activity 3

Read the following extract from Augustine’s Confessions. What happens to Alypius?

He said: ‘If you drag my body to that place and sit me down there, do not imagine you can turn my mind and my eyes to those spectacles. I shall be as one not there, and so I shall overcome both you and the games.’ […] When they had arrived and had found seats where they could the entire place seethed with the most monstrous delight in the cruelty. He kept his eyes shut and forbade his mind to think about such fearful evils. Would that he had blocked his ears as well! A man fell in combat. A great roar from the entire crowd struck him with such vehemence that he was overcome by curiosity. Supposing himself strong enough to despise whatever he saw and to conquer it, he opened his eyes. He was struck in the soul by a wound graver than the gladiator in his body […] As soon as he saw the blood, he at once drank in savagery and did not turn away. His eyes were riveted. He imbibed madness. Without any awareness of what was happening to him, he found delight in the murderous contest and was inebriated by bloodthirsty pleasure.

Discussion

Augustine paints a powerful picture of how Alypius’ confidence in his ability to stand firm against the cruelty of the games is swept away by the febrile atmosphere in the amphitheatre. As soon as he opens his eyes, Alypius is transfixed by the violence; nor is it simply grim fascination, but rather, as Augustine describes it, he becomes almost drunk on the pleasure of watching the bloodshed, such that he loses any sense of himself.

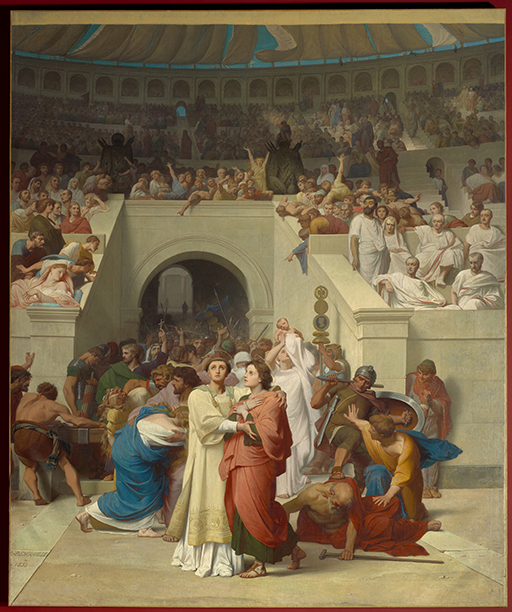

As well as motivating the moral critique of the games by writers such as Tertullian and Augustine, the Colosseum assumed another important role in the development of Christian culture and identity as a site strongly associated with the persecution of its followers. Although the execution of Christians by various means in the arena was sporadic, and in no way limited to this group, the martyrdom of Christians became strongly associated with the Colosseum, and a dominant feature of many modern recreations of the site – such as the nineteenth century painting in Figure 3. From this brief consideration of the Colosseum’s history in later antiquity, then, we can start to see how different layers of meaning attach themselves to ancient places and practices. What was initially a symbol of Roman greatness quickly became, from a different perspective, a symbol of Roman immorality and cruelty. After the Roman empire fell and the Colosseum collapsed into ruin, it took on additional meanings as a symbol of how even the greatest empires perish.