4.3 Characterisation and sexual stereotyping

The choice of pose was also intended to echo the limited positive characterization of the expression. Distinctions were inevitably drawn between poses regarded as suitable for males and those considered appropriate for females. Men were allowed greater variety of poses than women.

The pose of a lady should not have that boldness of action which you would give a man, but be modest and retiring, the arms describing gentle curves, and the feet never far apart.

(Wall, 8 March 1861, p. 110)

For both men and women it was routine practice to find head and body set at slightly different angles. This prevented a wooden appearance by introducing a slight suggestion of movement into the composition. In portraiture in general it was normal for the gaze to follow the direction of the head.

Activity 9

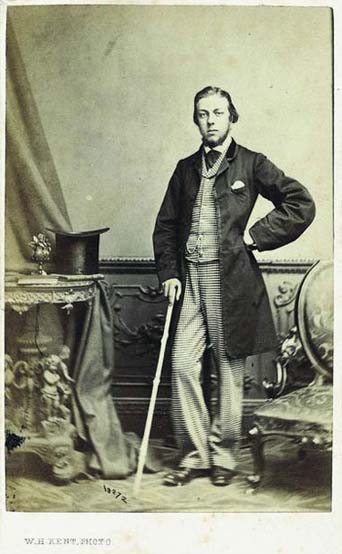

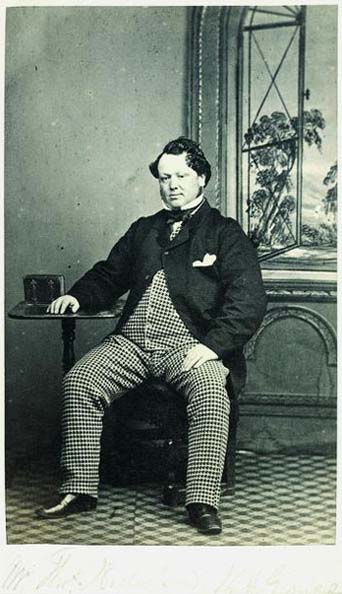

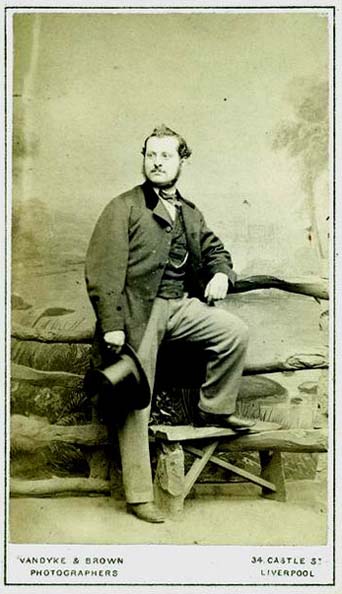

Spend at least 5 minutes comparing these portraits of men and women. Look in particular at the position of arms and legs, the set of the head and the direction of the eyes.

What differences in pose can you identify between the men and the women? Make a note of your findings. Do you think that these differences help to suggest different qualities? If so, what qualities can you identify?

Answer

The poses of the women are characterized by a relative lack of exertion or activity. The lack of movement can convey repose, calmness, quiescence or even passivity. The slight variation in the angle of head and body, allied with their inactive poses, adds grace. Whether standing or seated women normally keep their arms close to the body. This suggests self-containment and little interaction with the outside world.

It is less common (though certainly not unknown) to find women gazing directly at the viewer. The frontal gaze can project strength, courage and engagement. It can also be perceived as confrontational. Women usually have their gaze averted. If they are looking downwards, the pose can suggest meekness, modesty and docility. In general, however, gaze has to be interpreted in relation to other elements of the image.

In marked contrast with the women, the men can cross their legs, set them apart or stand with one foot higher than the other. These poses can suggest a sense of ease with the world, alertness, energy and activity. The different angle of head and body in males can sometimes be used to emphasize the suggestion of action conveyed by arms and legs. Men can convey notions of authority, assurance, assertiveness and engagement with the world by projecting arms, knees, elbows, walking sticks, umbrellas and top hats into the space around them.