6 Portraits in the open air

6.1 The rise of the itinerant photographer

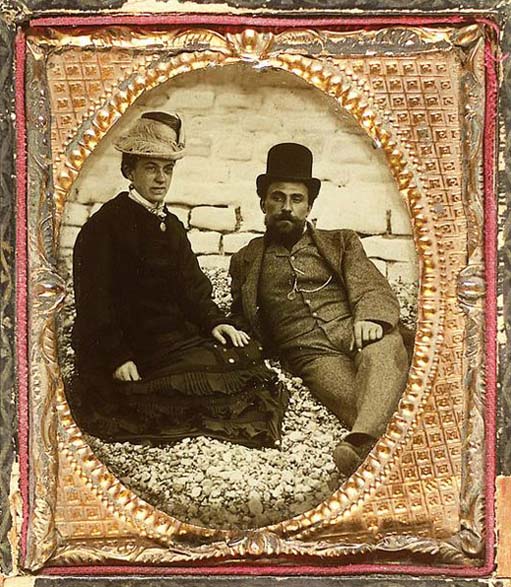

Happily, not all early family photographs were taken inside conventional studios. Sitters were frequently photographed in the open air or in temporary, makeshift studios. Portraits were taken in the street, at the fairground, at the seaside, at local beauty spots and in the parks and commons where town dwellers went for relaxation and entertainment on Sundays and holidays. Itinerant photographers who worked these venues would set up shop for the day, the week or longer, depending on situation and circumstance.

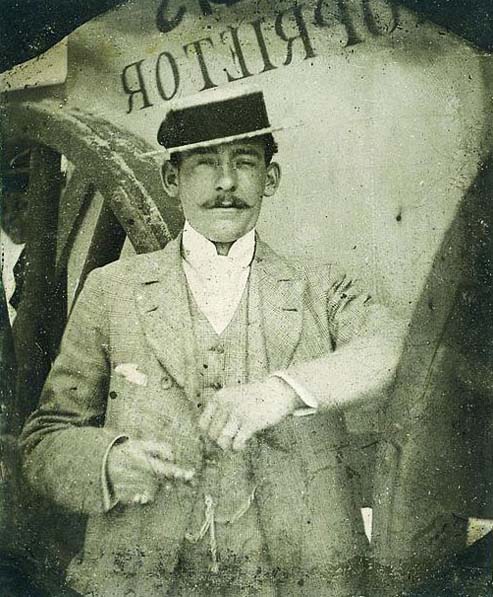

Photographers could exploit a clientele of day-trippers and temporary visitors by offering a while-you-wait service. For this they employed a process known as the wet collodion positive. A sheet of glass was coated with sticky collodion, immersed in the light sensitive silver nitrate and exposed in the camera while still wet. (It remained sensitive only while it was wet.) The exposed plate was chemically processed and then bleached. When placed against a black background (or coated with Bates's Black Varnish) the image appeared positive. The absence of the need for daylight printing speeded up and simplified the process. For a small additional charge, the glass plate was housed in a case or frame. The whole procedure took about 5 minutes from beginning to end. In Britain these images became known as cheap glass positives; in America they were called ambrotypes. Image 76 is an example of this.

The glass positive was gradually supplanted by the ferrotype (also called tintype). In the ferrotype the glass base was replaced by a thin sheet of enamelled iron. The ferrotype was cheaper and less liable to break but also generally poorer in quality since the highlights were rarely white. Since there was no negative involved in the process the ferrotype images were usually laterally reversed. However, ferrotypes could be produced in multiple copies using cameras with multiple lenses and scissors to cut the thin sheets of iron after exposure and processing. The ferrotype became popular in Britain from the 1870s.

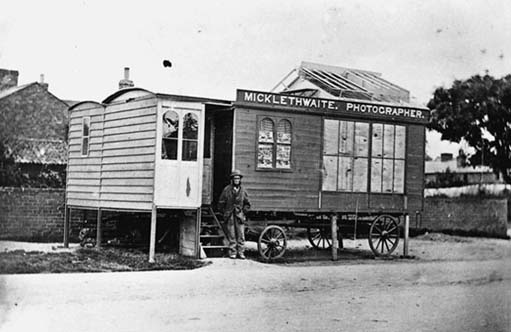

There was great variation in the equipment used by different itinerants. Basic necessities included a camera, tripod and some form of dark box (usually on wheels) in which to sensitize and process the negative. Dark boxes could be crude adaptations of prams or market barrows, or neat, purpose-designed, business-like constructions.

Some itinerants could afford to invest in horse-drawn caravans which combined living accommodation with glazed studios and darkroom facilities. These vans were moved from venue to venue by horses hired for the journey. The wooden structure to the left of the steps into Micklethwaite's studio (Image 79) was a temporary extension which would have been dismantled and stored while the van was on the move.

Other itinerants worked in canvas tents pitched on the sands or in the fairground.

There was a similar variation in the pattern of itinerant activity. Some studio proprietors might take to the road in the summer months and some itinerant photographers might take up entirely different occupations to tide them over the winter months. Itinerant operators usually worked on spec rather than to commission and they were frequently regarded with contempt by established studio proprietors with good connections.

We are going to devote a little attention to outdoor work in the street and at the seaside, as these venues feature prominently in the typical family album.