2 Some examples

The World Religions model is a bit like the Premier League, but without relegation – the members are automatically treated as an elite group. (Other terms have the opposite function, like ‘cult’, which automatically marks something as ‘Not really’ a religion… But that’s a conversation for another time!)

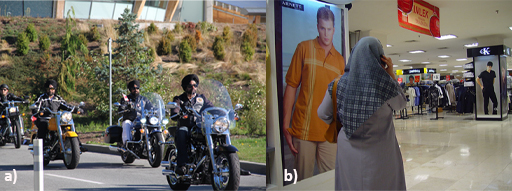

But the fact is that the members don’t have as much in common as it might seem – and grouping them together as World Religions helps to present them as though they do. Even so, when we look more closely, it’s clear that you have to present these traditions in very specific ways to make it work at all:

- Hinduism – Hinduism is perhaps the clearest example of the influence of colonialism. ‘Hinduism’ – as a specific religious category – exists specifically because the British census needed a box for those who weren’t Christian or Muslim to tick. Of course, people were already doing and thinking the things they always had, but once it was recognised as a single religion, it was increasingly presented as a unified ‘system of belief’, with the Brahmins as priests, the Vedas as Bible and Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva as a Trinity of supreme Gods. The problem is that this represented only a small percentage of Indians, although it suited the educated elites, especially those who wished to portray India as a unified, modern nation on the international stage. Even today, religion in India is presented in introductory textbooks as a single, albeit multifaceted, tradition, ignoring literally hundreds of millions of people’s beliefs and practices.

- Judaism – is not a good fit with the World Religions model. It isn’t particularly large, with around two per cent of most western countries claiming Jewish identity. But identity, in this context, does not always mean what we would typically understand as religiously Jewish identity, as Jewishness is also considered a cultural and perhaps even ethnic identity. In fact, even in Israel, the only Jewish-majority state in the modern world, most people are secular Jews. This is also tied to the fact that Judaism is not a religion with a universal message – the covenant with God was with the Jews alone, and this identity is passed down the Mother’s line. It is possible to convert or marry in, but it’s not a tradition that actively evangelises. In fact, the position of Judaism in the World Religions model probably has more to do with its relationship to Christianity – and particularly the way that it is perceived by some as a forerunner of Christianity. For the Victorian colonial powers who saw Christianity as the pinnacle and end-point of all religion, this would be enough to grant it a permanent place at the table.

- Religion in Japan – censuses show religious identification in Japan as being more than 100%! That’s because Japanese people are happy to tick several boxes, because they tend to see religion as something you do, rather than something you are. They see no contradiction in having Buddhist funerals and Christian weddings, while taking part in public Shinto ceremonies. In fact, the idea of Shinto as a (single) religion was more-or-less forced on Japan during the US occupation after the end of the Second World War. This underlines that while the roots of the World Religions model is in the colonial period, its effects were being played out throughout the twentieth century, and continue today.