Find out about The Open University's English courses

Phone messaging apps are first and foremost a means of relating to, or connecting with, other people. This means that many anxieties about messaging are really concerns about relationships. Importantly, relationships always involve a balance between, on the one hand, expressing solidarity and connecting with others; and, on the other, maintaining independence, or keeping a distance. This is evident in the way we organise and live our lives but it can also be seen in the way in which we interact with others. When we talk – or sign, or write, or message – we are always working to maintain an appropriate social distance between ourselves and the people we are interacting with. The distance at which we hold people depends on our relationship with them as well as our mood or priorities at the time.

Messaging apps challenge our need to keep people at an appropriate or comfortable distance because it has the potential to make us available at any time – we are potentially ‘always on’. Our friends know that we keep our phones to hand and they can see when we have read their message. We can control this to some extent by not opening a message or by turning off the read-receipt function. But we also manage closeness and distance through our interactions; that is, by using language in interaction to construct an appropriate distance between ourselves and our different contacts, while also being careful to maintain our connection with them.

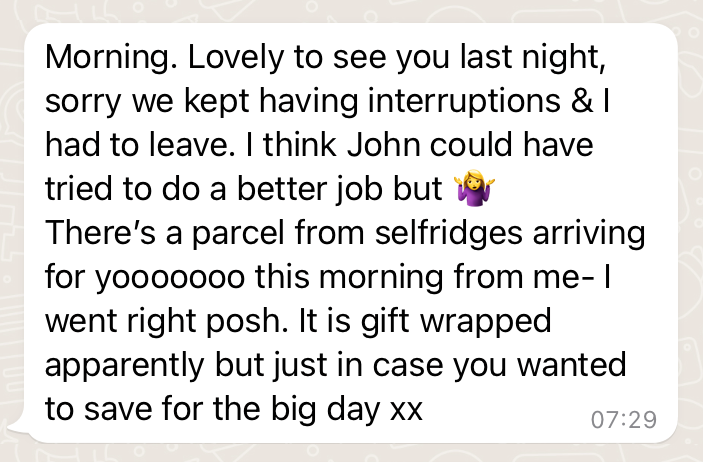

In my research with mobile messaging users, I’ve explored how this happens in practice. For example, on a Monday morning shortly before Christmas 2021, project participant Hannah receives a message at 7:29am while she is still sleeping from her old friend Hazel.

Her phone is downstairs in the lounge, but she is alerted to the message once she is awake by her smartwatch. Nonetheless she does not answer the message until an hour later, after feeding her guinea pigs and having breakfast. When I asked Hannah why she did not reply immediately, Hannah told me she was unusually busy at work and did not want to be distracted by getting into a long chat with Hazel. Not only is her interaction with Hazel shaped by what she is doing at the time – getting ready for a busy work day – but she deliberately delays sending a response as a tactic to avoid initiating a conversation.

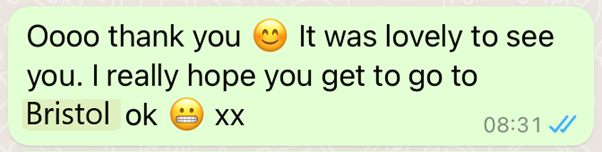

If we look more closely at Hannah’s message to Hazel, sent at 8:31am as she settles down to work, we get a sense of how carefully – if subconsciously – Hannah is working to balance connection and distance.

Although Hannah has deliberately delayed a reply, her message is nevertheless designed to engage or connect with Hazel. This is evident in the way her language choices echo Hazel’s, suggesting that she’s paying close attention. For example:

- the repetition of ‘o’ in Hannah’s ‘Oooo’ echos Hazel’s own vowel repetition in ‘yoooooooo’

- Hannah’s phrase ‘It was lovely to see you’ is a reformulation of Hazel’s ‘Lovely to see you last night’

- and the two kisses (‘xx’) at the end of Hannah’s message also parallel Hazel’s.

Hannah also refers explicitly to their shared communicative history, specifically to their Skype chat the evening before when Hazel talked about a planned trip back to their home city. By paying close attention to Hazel’s wording and their earlier chat, Hannah is showing that she’s aligning with Hazel – she’s maintaining their connection even as she holds Hazel at an appropriate distance.

This balance between connecting and controlling isn’t unique to messaging – quite the opposite. But the potential intimacy of messaging and the fact that people can contact you at any time bring this tension to the fore. It requires new communication strategies to keep people at an appropriate distance – close, but not so close that it interrupts what you’re doing.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews