Find out about The Open University's English courses

Digital technologies such as WhatsApp and other messaging apps are now deeply embedded into many people’s daily lives. Mobile conversations interweave in complex ways with offline activities, interrupting and being interrupted by what we’re doing in the real world. Phone messaging adds another layering to our already busy lifestyles, both facilitating offline tasks and compounding busy schedules – another set of tasks to fit in and additional people to coordinate them with. How do we manage the complex multitasking that comes with being online and connected in the twenty-first century?

One key observation from my research with users of messaging apps is that people have developed both technological and social strategies for prioritising and managing messages in the context of their busy domestic, social and working lives.

Technological strategies include:

- turning off notifications, so that people can check messages when they choose to do so. This is done most often for large group chats. In this way, people treat messaging apps as a sort of ‘noticeboard’ they can come back to when it suits them

- keeping phones on silent, or putting phones on silent at certain times, such as when they are at work, with other people, or sleeping

- disabling the read-receipt functionality that enables other people to see if they have read a message, mainly to retain privacy and avoid any pressure to reply immediately.

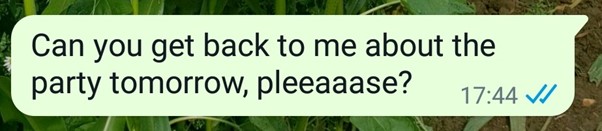

The blue ticks (shown in the above image) that tell someone you’ve read a WhatsApp message (but not yet replied to it) can be turned off in your privacy settings.

Alongside these technological strategies are certain social principles by which people manage their mobile conversations. On the one hand, it appears that people’s use of messaging is shaped by what else they’re doing when they are messaging. For example, most people in my research claim they frequently, or sometimes, send messages while watching television or working but very few say they would do so during lunch with a friend. Some people explicitly cite their belief in prioritising people who are physically present. Others describe putting their phone away when they don’t want to use it or be distracted.

On the other hand, when asked what would prompt them to respond immediately to a message, only a few people put it down to what they’re doing at the time. Instead, most suggest that the speed of their reply is determined by how urgent they think the message is, their relationship with the sender, or both.

This challenges the idea that mobile messaging is necessarily a quick and instantaneous way to communicate. Instead, people are clear that they shouldn’t always feel under pressure to reply straight away and can do so in their own time.

‘People are attempting to assert control over their communicative practices’

People also accept that this is true for their friends and family, recognising that a lack of response from a contact might be due to an array of factors, including their contacts’ busy lives and other, more pressing priorities.

People also accept that this is true for their friends and family, recognising that a lack of response from a contact might be due to an array of factors, including their contacts’ busy lives and other, more pressing priorities.

These strategies and principles suggest that people are attempting to assert control over their communicative practices. In particular, we try to resist the social pressure to be constantly available, or ‘always on’. We do so by keeping our phones on silent and turning off notifications, choosing when to engage with mobile messaging apps, and asserting our and others’ right to reply in our own time. This suggests an awareness of the need to push back against social and technological demands and to use technologies in ways which work for us.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews