Find out about The Open University's English courses.

A lot has been written about the ‘attention economy’ – the way that social media companies, businesses and advertisers compete to gain people’s attention in order to boost sales. They do this because otherwise their message or product gets lost in the overwhelming amount of information that circulates on the internet.

Attention is important to our personal online interactions, too. In a world of messaging apps and social media sites, many of us are constantly engaged in multi-tasking – shifting our attention between multiple encounters and activities, both online and offline. Importantly, how we distribute our attention has a social dimension – we have to secure other people’s attention, show that we are paying attention to others, and interpret others’ displays of attention. Mobile messaging conversations are not only shaped by the other things we are simultaneously attending to, but also by our need to be seen to be paying attention to others.

One way to show you’re paying attention online is through a timely response. Rhythm and pacing are central to spoken face-to-face conversation – speakers and listeners act like a musical ensemble, sharing the same beat as they respond to each other and take turns. Timing in online interactions is somewhat different, but equally important. Short response times, for example, can suggest intimacy, urgency, approval, presence; delayed replies may suggest a lack of engagement or involvement in an exchange. This in turn can (however unwittingly) suggest something about the status of a relationship. Indeed, participants in my research suggest they respond more quickly to people they are closer to: “I usually only respond immediately to my wife”, one survey respondent told me.In my research, I’ve explored what people are doing when they sent mobile messages, and how this determines the kinds of conversations they have. My research suggests that the rhythm of mobile messaging conversations is shaped by what people are paying attention to and how they shift between one focus of attention and another. The different patterns of engagement are illustrated below.

Many people find time in their day to ‘check their messages’ when they pick up their phone, read incoming messages and send messages, often to multiple threads. I call this device attending. For example, Alex finds time to sit on the sofa, before his children are awake or while they are in the bath, and go through his messages. Eva puts aside some ‘me time’ after putting her son down for a nap, during which she responds to her messages before engaging in prayer. This pattern of engagement involves conversational delays followed by an increase in tempo. Interestingly, these messages are on average longer than other messages, suggesting that people write more when they can do so at a time of their choosing.

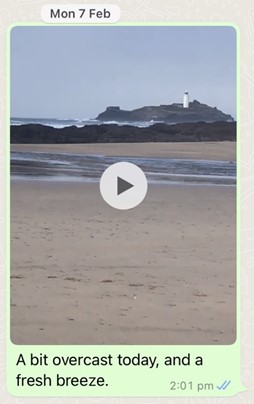

On

other occasions, people pick up their phone in order to share a photo or video they’ve

taken. In these cases, people’s attention is less on their device, or even the

people they’re contacting, but on the world around them, and the rhythm of

their online conversation is shaped by that of their offline world. Replies aren’t

expected; and when people do reply, they tend to engage in what’s been called

‘ritual appreciation’, characterised by repeated punctuation (!!!), exclamations and emoji. This is world

attending. For example, Beth shares with her family photos of the

origami flowers she and her girlfriend have just made in an online class; Phil

shares with his children a video of his walk on the beach.

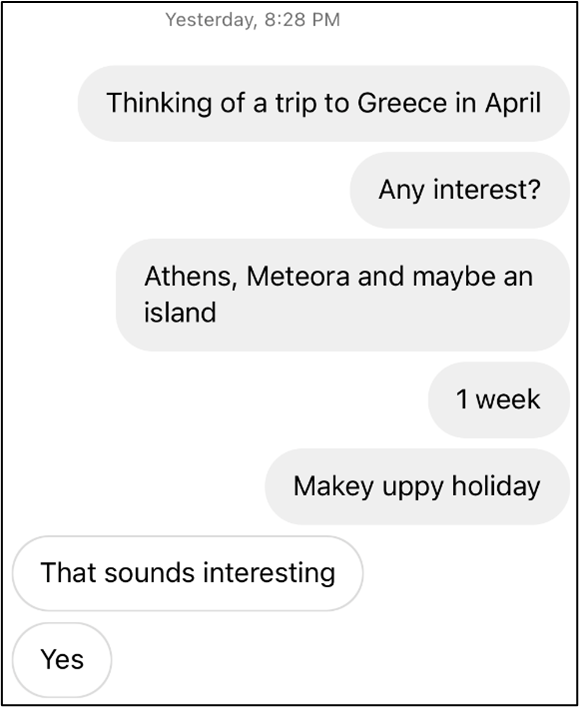

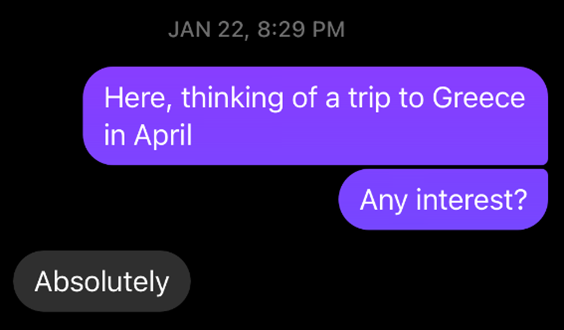

On

other occasions, people pick up their phone in order to share a photo or video they’ve

taken. In these cases, people’s attention is less on their device, or even the

people they’re contacting, but on the world around them, and the rhythm of

their online conversation is shaped by that of their offline world. Replies aren’t

expected; and when people do reply, they tend to engage in what’s been called

‘ritual appreciation’, characterised by repeated punctuation (!!!), exclamations and emoji. This is world

attending. For example, Beth shares with her family photos of the

origami flowers she and her girlfriend have just made in an online class; Phil

shares with his children a video of his walk on the beach.

In contrast, only on some occasions do messaging app users engage in what I call focused encounters; that is, real-time messaging-based conversations to which they appear to be devoting their full attention – and which might most closely resemble face-to-face encounters. For some people, these may stand out from their more typical messaging practices: as Naomi explained to me, her focused encounter with a bereaved friend is markedly different from her other interactions; she gives her full attention when her friend reaches out to her. Most mobile conversations in my dataset don’t end; they simply drop off to be picked up again later. At the end of this focused encounter, however, Naomi takes her leave and explains why she has to go.

Such focused encounters – which we might assume are the norm in spoken, face-to-face conversations – are perhaps the exception to the rule of most mobile conversations.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews