Find out more about The Open University's Language courses and qualifications.

Cumbre Vieja erupting in 2021During the eruption of Cumbre Vieja (a volcano on the Spanish Island of La Palma) in 2021 and its aftermath, the public were given a crash course on scientific terminology. However, a more

colloquial word from the Canary Islands proved to be the favourite: ‘fajana’, generally

meaning flat terrain at the foot of a steep slope, created by fallen debris. It

refers specifically to the new coastal territory formed by lava on its way into

the sea.

Cumbre Vieja erupting in 2021During the eruption of Cumbre Vieja (a volcano on the Spanish Island of La Palma) in 2021 and its aftermath, the public were given a crash course on scientific terminology. However, a more

colloquial word from the Canary Islands proved to be the favourite: ‘fajana’, generally

meaning flat terrain at the foot of a steep slope, created by fallen debris. It

refers specifically to the new coastal territory formed by lava on its way into

the sea.

Crises can cause the spread of specialised vocabulary or seemingly remote dialect, but they can also bring about entirely new situations that need to be named from scratch. These new words and expressions are called ‘neologisms’. The COVID-19 pandemic has given way to scores of these, even two years into the pandemic after the emergence of the Omicron variant.

A poignant example has been seen in China where the zero-COVID policy has meant compulsory stays at centralised quarantine locations for people testing positive for COVID-19, even when asymptomatic.

Kwai Chung, China, lockdown queue for a Covid test, January 2022.

Kwai Chung, China, lockdown queue for a Covid test, January 2022.

The resulting situation illustrates many of the issues around language and culture in times of crisis. The Chinese public has reportedly started using a very particular term, ‘little sheep people’, when tracking positive cases in their own area, as well as nationally. Why? The explanation is a linguistic one. According to Mimi Jiang (2022) and Manya Koetse (2022), the word used to refer to positive test results (yáng 阳) happens to be pronounced in the same way as the word for ‘sheep’ (yáng 羊). For this reason, many started to use the phrase ‘little sheep people’ to refer to those who had tested positive. It could be said that a neologism was created here by a process of semantic shift. In any case, social media users have raised concerns that this term reinforces stigmatisation of a group of people who have become very vulnerable in Chinese society (Koetse, 2022).

Ukraine invaded

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes a very rich example of the complex interplay of language and culture in times of crisis. But as other global events continue to reverberate and enmesh themselves in our lives, we are presented with many opportunities to enhance our cultural awareness and reflect on how we use language. When the Russian army started invading Ukraine in February 2022, politicians, journalists and the general public were urged to abandon the use of Russian terms to refer to cities and areas of Ukraine, opting for: Kyiv instead of Kiev; Dnipro instead of Dnepr; Odesa instead of Odessa; and Kharkiv instead of Kharkov (Motyl, 2022). Many people across the world must have been unaware that these were originally Russian words, but Ukrainian transliterations and pronunciations of these geographical areas constitute a mark of respect. As Ukraine fights to unburden itself of this current and most damaging attempt at Russification (namely, annexation), the international use of Russian words to denote parts of their country must feel particularly offensive and painful.

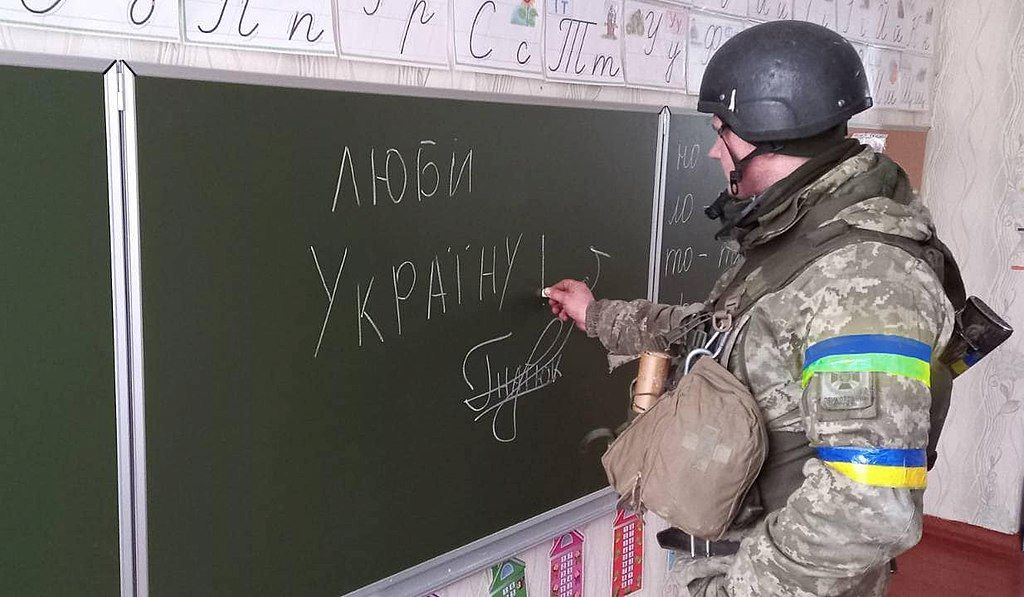

I love Ukraine, written by a Ukranian border guard, on one of the war fronts.

I love Ukraine, written by a Ukranian border guard, on one of the war fronts.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a large number of medical terms into common use, such as ‘viral load’ or ‘spike protein’. Likewise, a violent crisis such as a war involves a range of specialised vocabulary. Early reports from Ukraine showed the population of Kyiv and other cities producing Molotov cocktails that had been renamed ‘Bandera smoothies’. Both terms are neologisms by extension and include cultural references, which can be an important part in the connotations of words. Molotov was a Soviet minister who, when bombing Finland during the First Finnish-Soviet War (1939-1940), claimed to be sending food parcels; in retaliation, the Finns referred to their own bottle firebombs as ‘Molotov cocktails’ (Withers, 2022). These ‘cocktails’ have been updated to ‘smoothies’ in order to downplay any alcoholic connotations, while painting a picture that would be familiar to cosmopolitan allies. It is effective propaganda, as it stirs empathy but also drives home the important point that countries beyond Ukraine could find themselves the victims of Putin’s attacks. The use of the surname Bandera is a Ukrainian cultural reference to replace the use of Molotov. Stepan Bandera was a Ukrainian nationalist fighter against Soviet Russia (Motyl, 2022).

Digital tools and humanitarian support

In times of crisis, many population groups find themselves disproportionately affected because of their ethnic origin, race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status and/or disability, with intersectionality sadly leading to unique situations of hardship, alienation and discrimination. Grass-roots organisations often step in, and digital tools support medical and humanitarian efforts in the response to crises, often involving the participation of the general public, such as the ZOE Health Study in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Data for Ukraine project.

Data for Ukraine analyses Twitter data in order to detect a variety of developing events in Ukraine: civilian resistance; displacement of population groups; human rights abuses; and humanitarian needs (Machine Learning for Peace, 2022a). For this purpose, over 600 keywords in Ukrainian and Russian are searched, and these are supplemented by other terms and phrases commonly used on the platform in relation to the war in Ukraine (Machine Learning for Peace, 2022b).

A proactive engagement with complex aspects of language and culture is paramount in times of crisis to gain a deep understanding of the full situation. This knowledge allows individuals and societies to deal with the consequences of crises and to communicate in an effective and appropriate way.

Find out more

The Open University course LG005 The Languages of crises guides learners in this process, laying theoretical foundations, developing relevant skills and fostering critical thought. Above all, it opens up a space to discuss with other learners the unique insights gained when looking at crises through the lenses of languages and cultures.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews