3.1 The brain, neuroplasticity and resilience

Scientists have developed some understanding about what happens in the brain when people are exposed to stressful situations, and about how the adolescent brain differs from the adult brain. Combining this scientific knowledge can help deepen understanding about resilience in young people and demonstrate how good social support can influence changes in the brain via neuroplasticity.

In session 2, you found that in adolescence the prefrontal cortex is undergoing significant change. This area of the brain is used for the ‘executive functions’ of planning, inhibiting inappropriate behaviour, understanding other people and social awareness. During adolescence, the prefrontal cortex is being re-shaped and ‘pruned’. At the same time the limbic system, which is responsible for emotion, is exceptionally active (Blakemore, 2019). Combined, these changes can make young people particularly sensitive to adversity because the prefrontal cortex becomes temporarily less able to interpret and moderate the emotional responses of the limbic system.

The brain pruning and reshaping described above are aspects of neuroplasticity that significantly (but not exclusively) take place during adolescence. In addition, the nerve pathways formed during early childhood and adolescence show neuroplasticity by changing in response to an individual’s experiences in life (Schauss et al., 2019). Brain activity is highly influenced by social interactions and the wider social environment, whether for better or worse. There is some evidence that adverse experiences can impair development of the prefrontal cortex in young people (Hunter, Gray and McEwen, 2018). On the positive side, neuroscience suggests that supportive social interaction can lead to beneficial brain adaptations and enable a young person to learn resilient behaviours.

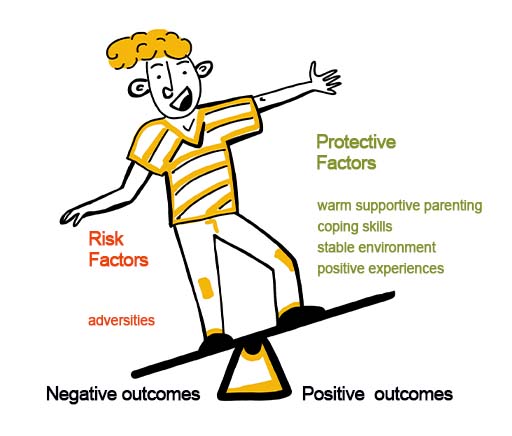

Figure 6 demonstrates how potential negative outcomes for a young person can be ‘tipped’ into positive outcomes by the protective factors of ‘warm supportive parenting’, ‘coping skills’, a ‘stable environment’ and ‘positive experiences’. Remember that negative outcomes from adverse experiences are not inevitable.

Whatever the social environment, anyone caring for a young person will realise that young people bring their own personal characteristics to any situation. Some individual differences can be attributed to their inherited genes. There is clearly an interaction between ‘nature’, which is genetically determined, and ‘nurture’, which encompasses experience. In the next activity, you’ll learn about a simple but effective analogy for thinking about how interaction between a young person’s genes and the environment can affect the brain.

Activity 6: The resilience seesaw

Watch the brief video explaining the dynamic relationship between the developing brain, a person’s genes, and the environment. What is the role of genes, the environment and learning in this process? Write your notes in the table provided.

| Genes | Environment | Learning (i.e. brain changes) |

|---|---|---|

Answer

Here’s an example of notes on the video:

| Genes | Environment | Learning (i.e. brain changes) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Research in genetics can help to explain some differences between young people,indicating that a young person’s sensitivity to environmental challenges has genetic origins. For example, Boyce and Ellis (2005) suggested that genetic makeup predisposes how sensitive young people are to the stresses they experience during childhood. Albert et al. (2015) reported a specific gene variant among children who appear highly sensitive to their environments and are particularly vulnerable to stress. These genes are linked to chemical receptors in the brain, which in combination with family stress can lead to social and emotional problems later in life.

Studies in neuroscience and genetics strengthen our understanding of the links between the brain, resilience and mental health. However, there is much more research to be done before we can fully explain how these effects interact and neuroscientists are keen to acknowledge the important part played by experiences and influences within the environment. The next section explores further how resilience can be fostered in young people who may have become vulnerable through adversity.