2 Sarah Baartman, the ‘Hottentot Venus’

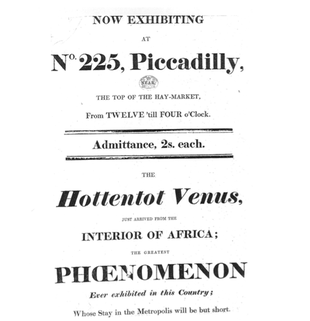

Saartjie Baartman (c.1775–1815), a member of the Indigenous Khoikhoi people of South Africa, had been sold into slavery and was brought to London by a Scotsman who procured people for display. Given the European name ‘Sarah’, she became widely known by the pejorative term ‘Hottentot Venus’ (European settlers used the name Hottentot to describe nomadic peoples like the Khoikhoi in South Africa). Satirist illustrators focused on her physique, especially the perceived enormity of her buttocks. In 1801, she was exhibited almost naked at No. 225 Piccadilly, London, before spectators who paid two shillings (see Figure 2). According to the evidence, she was ‘led by her keeper, and exhibited like a wild beast’ and the spectators were encouraged to prod her (Qureshi, 2011, p. 146).

The term ‘keeper’ is notable, as she was then sold to an animal trainer and exhibited in Paris. Accounts record she was a degraded and unwilling participant, hitting her minders when she could. She refused to give the anatomists, who studied her, permission to conduct an intimate examination. Throughout the century displayed people often resisted being used as specimens of scientific study, for example refusing to be measured or to pose naked for photographs. Members of Britain’s slavery abolition movement also tried to resist her exploitation through a newspaper campaign and a failed legal action to halt the exhibition.

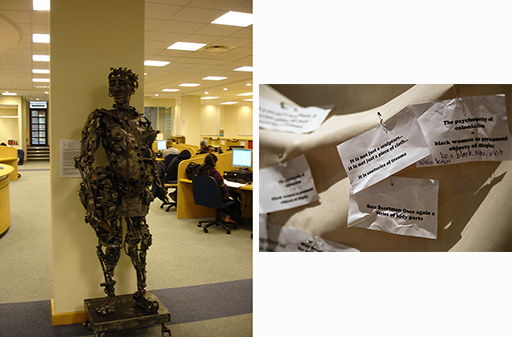

But even in death, the exploitation continued. Her body was dissected, and her skeleton and a plaster replica of her body were displayed in Paris. They were removed in 1970, following feminist protests at the violation of her dignity. In 2002 her remains were returned to Africa, after an eight-year restitution campaign instigated by South African President Nelson Mandela. At her funeral, Mandela’s successor, President Thabo Mbeki, said her story was emblematic of the colonial abuse of the African continent. Today a sculpture of Baartman, at the University of Cape Town, provokes debate about the colonial abuse of women and how racism was legitimised by science, as shown in Figure 3.

For most of the nineteenth century it was common for individuals to be exhibited for public entertainment and ‘education’. Other Khoikhoi were displayed in exploitative exhibitions, prompting complaints from the Aborigines’ Protection Society. By the end of the century whole groups of people were displayed. They were often paid professionals, supported by recruiting officers who negotiated their permission to travel and work.