4 Fighting for and against France

Over time, the slave rebellion developed into a disciplined force led by a former enslaved person, Toussaint Louverture (c.1743–1803).

Under Louverture’s command, the Black insurgents allied with republican France to fight off a Spanish invasion. In 1796 Louverture was made deputy governor of the colony, and in 1797 commander-in-chief of the French forces in the colony.

By 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte (by then First Consul of the French Republic) decided to reassert Parisian control of Saint-Domingue, and he sent a large army there under the command of General Charles Victor-Emmanuel Leclerc. But Black Haitians suspected that France’s real aim was to restore slavery and the plantation system to the colony. Relations with Leclerc were poor from the start and soon deteriorated into open conflict. Leclerc promised Louverture immunity if he retired, but instead had him arrested and sent to France, where he died as a prisoner in 1803.

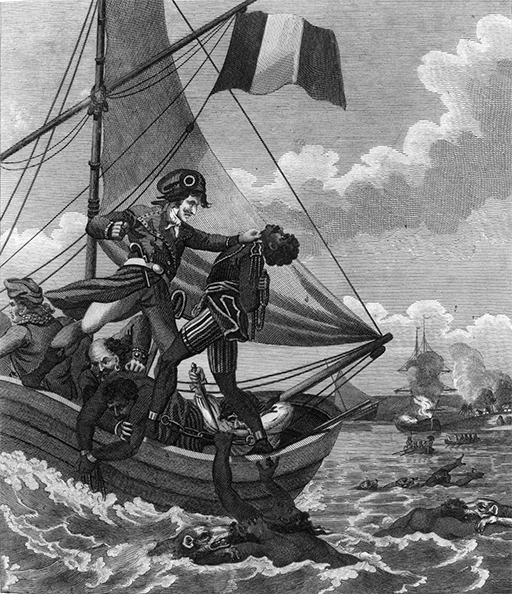

Meanwhile, French power in Saint-Domingue was disintegrating, despite brutal attempts to maintain control (represented artistically in Figure 5). Leclerc’s army was ravaged by Yellow Fever, while uprisings of the freed Black slaves and their supporters multiplied. Black and mixed-race forces united against the French, under the command of Louverture’s former main lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758–1806). Many Black women took up arms against the French, most famously Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniere who fought fearlessly at the Battle of Crete-a-Pierrot in 1802 (Girard, 2009).

Fighting was extremely brutal, but by November 1803 the remainder of the French forces had been evacuated. On 1 January 1804 Dessalines proclaimed the independent state of Haiti, stating that ‘we must live independent or die’. In the following months, his army massacred thousands of remaining white settlers, and he was crowned Emperor of Haiti.

Activity 1

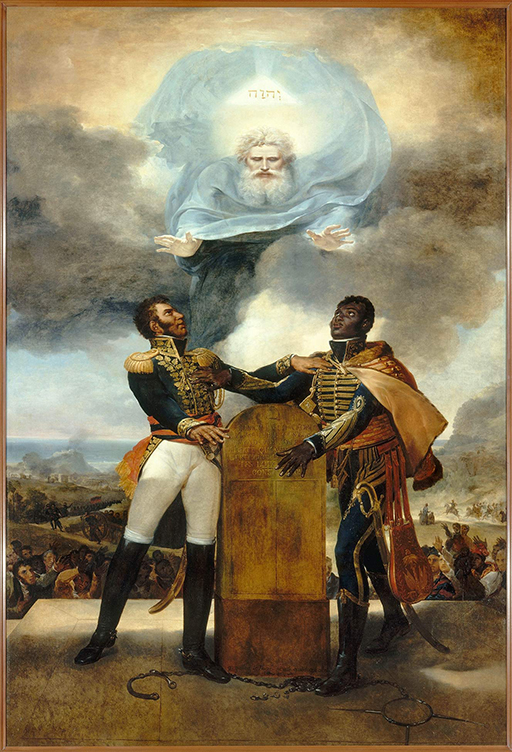

This painting below, Figure 6, represents the 1802 alliance of two leaders of the Haitian Revolution against Napoleon’s army: Alexandre Pétion, a prominent leader of the gens de couleur (left), and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, leader of the Black insurgents (right). It was painted in honour of the Haitian Revolution by a well-known French mixed-race painter, Guillaume Guillon-Lethière.

Take a few minutes to look carefully at Figure 6, focusing particularly on the three main characters. Don’t forget to also read the image caption. Then answer the following question:

- How does the painting represent the influence of France on the Haitian Revolution?

Discussion

This painting seeks to immortalise the union of Black and mixed-race slaves that allowed Haiti to defeat the French Republic and paved the way for Haitian Independence in 1804. But it also illustrates Haiti’s complex relationship with French and European culture: the oath of alliance is witnessed by a white Judaeo-Christian god, the two leaders’ elaborate uniforms are influenced by European standards of dress, and the altar inscription repeats the French revolutionary slogan vivre libre ou mourir (‘liberty or death’).

It is important to note, however, that the Haitian Revolution was equally shaped by a number of other influences, especially the Creole language and culture that had developed from contacts between West African enslaved peoples and European settlers.