2 Racial discrimination in colonial South Africa

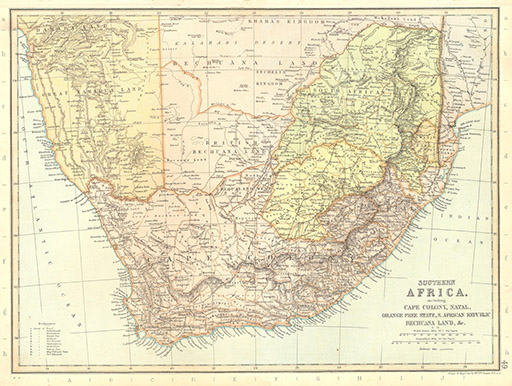

The state now called South Africa was colonised by white settlers from the Netherlands from the seventeenth century (known as Boers) who were subsequently followed by white settlers from Britain from the early nineteenth century. The settlers forcibly dispossessed the existing Black population from lands that were coveted by the settlers for agriculture and mineral extraction. British forces occupied Cape Town from 1795 to 1803 to stop the strategically important territory being occupied by the French, with whom they were at war. From 1806, British forces again occupied Cape Town. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, South Africa became part of the British empire.

Like other British colonies in Africa, British colonial subjects from India migrated to South Africa to seek work. Some of this migration was coerced, and these migrants were known as indentured labourers. This was a system of bonded labour introduced after the abolition of slavery in the British empire in 1833. Labourers were recruited from South Asia (as well as China) and signed a contract to work overseas for five years and sometimes more. The contract promised certain things in return for their labour, such as wages and land but, in reality, conditions of work and wages were very poor. This sort of bonded labour was enslavement in all but name.

The constituent territories that made up colonial South Africa had a wide variety of laws and regulations to racially discriminate between Black, South Asian (called ‘coloured’ people in nineteenth-century South Africa) and white people. These categories were politically created, and reflected contemporary racist attitudes based on white supremacy. The categorisation of people by skin colour and heritage (including religion) formed one of the bases of the racist apartheid system in South Africa after the Second World War. Apartheid, which means ‘apartness’ in Afrikaner, was a complex system of racial segregation that invaded many areas of Black South Africans’ lives, for example, where they could live, what pavements they could walk on, and what shops they could enter. What this racial discrimination meant on a daily basis was that if you were not legally classified as white, you were excluded from full equality and social and economic participation. Being defined as not white would lead to exclusion from full citizenship, exclusion from certain educational establishments, and certain kinds of jobs. Exclusion also extended to public and private places.

One example of this racial discrimination was about who could, and could not, sit in First-class train carriages. The segregation of train travel was because people of all socio-economic classes used the railways; many white people did not want to share their space in carriages with people who were Black Africans, and Indians, whom they believed to be inferior to them. Across the world, train travel was one of the most important areas of public transportation in the late nineteenth century. For the most part, it was relatively cheap for passengers and enabled people to travel relatively swiftly across short and long distances – in more comfort and more quickly than using roads or transport on water. This type of racist regulation of public transportation was common throughout the British empire, and was replicated in the racial segregation on buses and trains in parts of the United States until the mid-twentieth century.