2 Why are there so many ACL injuries in female sport?

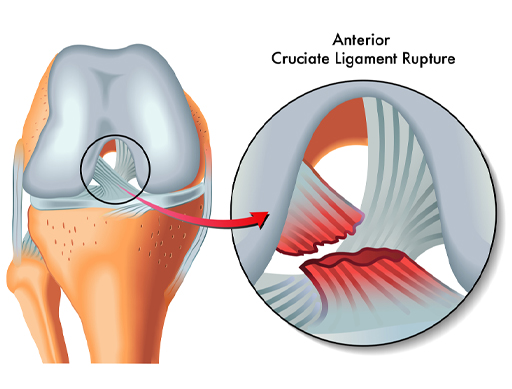

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of two ligaments in the centre of the knee joint that help provide stability (see Figure 1). The ACL goes from the back of the femur (thigh bone) to the front of the tibia (shin bone) and limits the forwards movement of the femur. The second ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), goes from the front of the tibia to the back of the femur and prevents the knee from bending backwards excessively (hyperextension). They form a cross shape, and this gives them their name ‘cruciate’.

The reasons why female athletes may experience more ACL injuries are complex, but they can partly be explained by changes that happen at puberty.

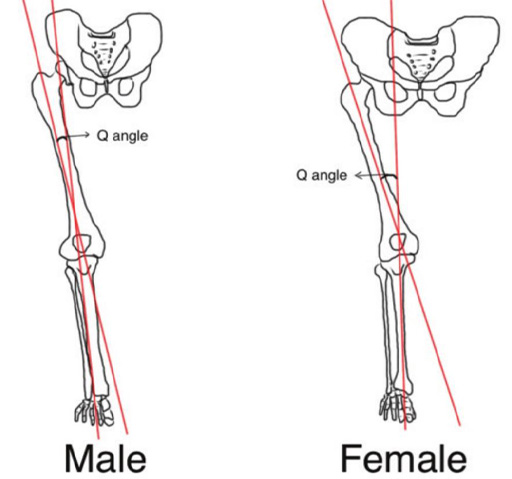

Post-puberty the male and female pelvis will differ as females will develop a broader pelvis to facilitate potential childbearing. This results in an increased angle where the femur connects at the knee joint with the tibia. This is referred to as the Q-angle and is around 16 degrees in females and 11 degrees in males. As well as affecting the way that forces travel through the leg to the knee and ankle it can cause a difference in the way the patella (kneecap) moves during exercise, and as a result females can experience more knee pain than males (Roush and Bay, 2012). This increased Q-angle can make it more difficult to prevent the knee from falling inwards when landing from a jump or turning quickly. If you examine Figure 2 you can see why this might be so.

Stability of the knee is provided by ligaments, such as the ACL, but it is also dependent on the strength of the muscles that control the knee. This includes the quadriceps at the front of the upper leg and hamstrings at the back, but also the gluteal muscles that control the hip. A weakness in gluteal muscles at the hip can result in the knee taking all the strain to prevent its increased range of movement.

There are some other factors that predispose female athletes to ACL injuries:

- Quadriceps dominance – female athletes are more likely to use their quadriceps to control the knee joint than male athletes. Male athletes tend to use strength in the hamstrings and gluteals, as well as the quadriceps, to share the load. The hamstrings will pull the tibia (in the lower leg) backwards to protect the ACL, while the stronger quadriceps in female athletes push the tibia forwards and place additional stress on the ACL (Greene, in Tomas and Whyatt, 2020).

- Ligament dominance – relative to male athletes the female athlete will have less musculature around the knee joint to stabilise it. As a result the ligaments have to take on more stability work and absorb forces placed on the knee joint. This increased load on the ligaments make them more susceptible to injury (Greene, in Tomas and Whyatt, 2020).