2.1 Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction

There are many theories about motivation at work but the influential ideas from American psychologist Frederick Herzberg are a useful starting point. He developed a theory of workplace motivation that identified factors that affected job satisfaction. This theory has proved popular with managers for many decades; it has been included here because it has become part of the ‘language’ of management.

Read the adapted extract below about Herzberg’s ‘Motivation–Hygiene Theory’ and some of the investigations that contributed to his theory.

Box _unit2.3.1 Herzberg’s ‘Motivation–Hygiene Theory’

Herzberg (1975) tested the different needs people have in the workplace. This was a more formal and wide-ranging investigation than the short interviews in a football club you viewed in the last section.

Herzberg and his colleagues asked people to recall times when they had felt especially satisfied or dissatisfied by their work, and to describe what factors had caused these feelings. The researchers found that two entirely different sets of factors emerged. Herzberg and his team called the factors connected with satisfaction, ‘motivators’, and those connected with dissatisfaction, ‘hygiene factors’. For example, a person who had listed low pay as a source of dissatisfaction did not necessarily identify high pay as a cause of satisfaction. Herzberg argued that improvement in some areas (the ‘hygiene factors’) would help to remove dissatisfaction, but that this would not increase satisfaction: that is, improving the ‘hygiene factors’ alone would not motivate people. For example, the absence of information about what is happening in an organisation may be a cause of dissatisfaction to an individual, but when that information is provided they are not necessarily more motivated; it is just that the dissatisfaction has been removed.

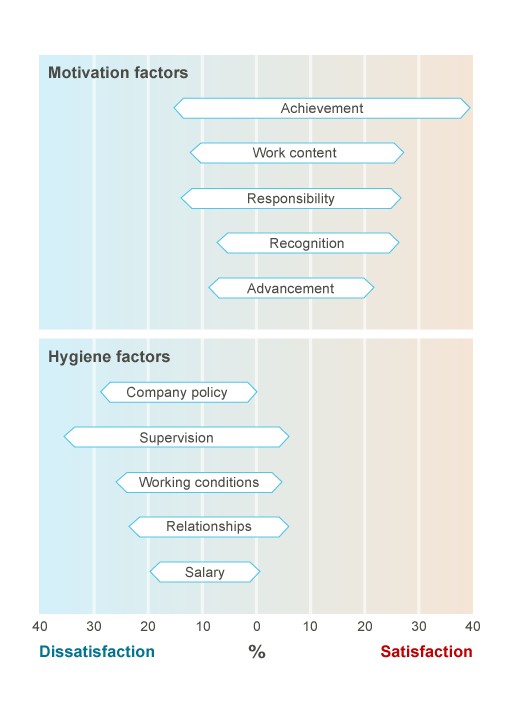

By asking people to categorise the causes of satisfaction and dissatisfaction under a number of headings Herzberg was able to record, for all the individuals in the group, the frequency with which each category had been noted as a satisfaction or dissatisfaction. A typical result is shown in Figure 2.

This shows that peoples’ work content (what they did in their work) was identified in this instance by 12% as a source of dissatisfaction, but it was mentioned by 26% as a source of satisfaction. Work content is viewed as a motivator, something more connected with satisfaction. If you were to ask about people’s work content in a football organisation it is likely that their passion for the game and the place it plays in their lives and the community would bring satisfaction.

Let’s consider the two main sources of job dissatisfaction in Figure 2, the hygiene factors. Company policy and administrative procedures were identified as an irritating source of dissatisfaction by 29%, but it was supervision (leadership and management) that was the greatest hygiene factor, singled out by 35% in this example. Notice that the proportions mentioning these factors as part of their job satisfaction was far lower (0% and 5% respectively).

Herzberg’s environmental factors which are capable of causing unhappiness, the 'hygiene' factors, can be thought of as having to be reasonably well 'cleaned up' as a prerequisite for satisfaction. Among the hygiene factors are:

- company policy

- supervision

- working conditions

- interpersonal relationships

- money, status and security.

The work content factors which lead to satisfaction, Herzberg’s ‘motivators’, are as follows:

- Achievement. This is a measure of the opportunities for someone to use their full capabilities and make a worthwhile contribution. It includes the possibilities for testing new and untried ideas.

- Responsibility. A measure of freedom of action in decision-taking, style and job development. Some people call this autonomy.

- Recognition. An indication of the amount and quality of all kinds of ‘feedback’, whether good or bad, about how you are getting on in the job.

- Advancement. This shows the potential of the job in terms of promotion – inside or outside the organisation in which you currently work.

- Work itself. The interest of the job, usually involving variety, challenge and personal conviction of the job’s significance

- Personal growth. An indication of opportunities for learning and maturing as a person.

From these types of findings, Herzberg drew some important conclusions:

- The things which make people feel motivated at work are not simply the opposites of the things which make them dissatisfied, and vice versa. The two sets of things are different in kind. People will not become motivated simply by removing causes of dissatisfaction.

- The things that make people dissatisfied are related to the job environment. In contrast the things that make people satisfied are related to job content. This is an important distinction.

- While those who have a satisfying job may have a higher tolerance of dissatisfiers, the dissatisfying factors can be so strong that the job becomes intolerable.

- Managers must therefore be concerned with ensuring both that causes of dissatisfaction are removed (or reduced as far as possible) and that opportunities for satisfaction are increased – that, in Herzberg’s terms, the job is ‘enriched’. Managers often fail to provide enough opportunities for employee satisfaction. Instead of drawing on real motivating factors and appealing to their employees desire to do a satisfying job, they use rewards and threats. In other words, managers can get it badly wrong, that is, they can demotivate. But getting it right won’t necessarily motivate people either, unless managers focus on those areas that make staff more satisfied, such as the content of their work and their responsibility levels and opportunities for self-fulfilment or development.

Involvement

Where staff at any level are ‘involved’ in decisions taken by their superiors, peers or even subordinates, all the motivators are brought into play. This is particularly the case where the decision under discussion will affect the person involved. For example, an experienced football team that have some involvement, however small, in the tactics they adopt in a particular match are more likely to commit to the approach if they feel they have contributed to it.

Involvement should produce the commitment to goals on which a sense of achievement depends. By involving people, leaders begin to recognise that their input matters and leaders increase people’s sense of responsibility. Interest in their job should be increased and leaders are providing their team with a broader view which provides both a learning opportunity and experience, of possible use in people’s further development.